(Press-News.org) Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

1. Infusion centers associated with substantially better outcomes than the ER for patients with acute pain events and sickle cell disease

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-7171

Editorial: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M21-2650

Summary: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/P21-0005

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

A prospective cohort study found that treatment at an infusion center (IC) is associated with substantially better outcomes than treatment in the emergency department (ED) for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crises. The findings are published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Vaso-occlusive events are excruciatingly painful and the leading cause of hospital and ED use in SCD. Although SCD is considered a rare disease in the United States, the burden of ED care and subsequent hospitalization is high. As documented in a systematic review, patients presenting to the ED with severe pain from these events are often faced with structural and interpersonal racism and sub-par care.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine studied 483 adults with sickle cell disease who lived within 60 miles of an IC in Baltimore, Milwaukee, Cleveland, or Baton Rouge between April 2015 and December 2016 to assess whether care in ICs or EDs would lead to better outcomes. They found that patients treated in an IC received parenteral pain medication an average of 70 minutes faster than those seen in the ED (62 minutes in the IC compared with 132 minutes in the ED). Patients in ICs were 3.8 times more likely to have their pain reassessed within 30 minutes of the first dose and 4 times more likely to be discharged home. These results suggest that ICs are more likely to provide guideline-based care than EDs and that care can improve overall outcomes.

According to the authors, these findings are important because adults with sickle cell disease have been historically underserved by the medical community. Better access to high-quality care should result in better outcomes for both the patient and the medical system.

Media contacts: For an embargoed PDF, please contact Angela Collom at acollom@acponline.org. To speak with the corresponding author, Sophie Lanzkron MD, MHS, please contact Patrick Smith at PJSmith@jhmi.edu.

2. Life expectancy gap closes dramatically between those with HIV and general population

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M21-0065

Editorial: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M21-2586

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

An observational cohort study finds that mortality among persons entering HIV care decreased dramatically between 1999 and 2017, with the largest decrease seen between 2011 and 2017. Those entering HIV care remained at modestly higher risk for death in the years after starting care than comparable persons in the general U.S. population. The findings are published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

HIV-related mortality has been decreasing since the introduction of effective treatment in 1996 due to improving treatment options and evolving care guidelines, but the extent to which persons entering HIV care in the United States have a higher risk for death over the years after linkage to care than their peers in the general population over the same period remains unclear.

Researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill used data from the National Center for Health Statistics to compare 5-year all-cause mortality between 82,766 adults entering HIV clinical care between 1999 and 2017 at 13 U.S. sites participating in the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) and a matched subset of the U.S. population. The persons in the general population were matched to those in NA-ACCORD by calendar time, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and county of residence. The researchers found that the difference in mortality between people with HIV and the general population decreased over time, from 11.1% among those entering care between 1999 and 2004 to 2.7% among those entering care from 2011 to 2017. Of note, mortality decreased across all demographic subgroups studied and decreased more among non-Hispanic Black people than non-Hispanic White people.

According to the authors, the decrease in mortality among persons with HIV likely reflects advances in care and treatment, new guidelines indicating earlier treatment, greater engagement in care, higher levels of viral suppression, a trend toward linking persons with HIV to care earlier in the course of infection (that is, at higher CD4 cell counts), and evolving patient characteristics in the cohort over time. They say this study is important because understanding differences in mortality between persons entering HIV care and the matched U.S. population is critical to monitor opportunities to improve care.

Media contacts: For an embargoed PDF, please contact Angela Collom at acollom@acponline.org. The corresponding author, Jessie K. Edwards, PhD, can be reached directly at jkedwar@email.unc.edu.

Also new in this issue:

The importance of clinician-educators

Centor

Annals On Call

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/A20-0016

INFORMATION:

LAWRENCE -- A new paper from a lead author based at the University of Kansas finds wetlands constructed along waterways are the most cost-effective way to reduce nitrate and sediment loads in large streams and rivers. Rather than focusing on individual farms, the research suggests conservation efforts using wetlands should be implemented at the watershed scale.

The paper, just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, relied on computer modeling to examine the Le Sueur River Basin in southern Minnesota, a watershed subject to runoff from intense agricultural production of corn and soybeans -- crops characteristic of the entire ...

In the movie "A Fish Called Wanda", the villain Otto effortlessly gobbles up all the occupants of Ken`s fish tank. Reality, however, is more daunting. At least one unfortunate fan who re-enacted this scene was hospitalized with a fish stuck in the throat. At the same time this also was a painful lesson in ichthyology (the scientific study of fishes), namely that the defense of some fishes consists of needle-sharp fin spines.

Two types of fin elements

Indeed, many fish species possess two types of fin elements, "ordinary" soft fin rays, which are blunt and flexible and primarily serve locomotion, and fin spines, which are sharp and heavily ossified. As fin spines serve the ...

For 400 million years, shark-like fishes have prowled the oceans as predators, but now humans kill 100 million sharks per year, radically disrupting ocean food chains. Based on microscopic shark scales found on fossil- and modern coral reefs in Caribbean Panama, Smithsonian scientists reveal the changing roles of sharks during the last 7000 years, both before and after sharks in this region were hunted. They hope this new use for dermal denticles will provide context for innovative reef conservation strategies.

Microscopic scales covering a shark's body--dermal ...

A study published the week of July 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences led by Michael Moore at Washington University in St. Louis finds that dragonfly males have consistently evolved less breeding coloration in regions with hotter climates.

"Our study shows that the wing pigmentation of dragonfly males evolves so consistently in response to the climate that it's among the most predictable evolutionary responses ever observed for a mating-related trait," said Moore, who is a postdoctoral fellow with the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University.

"This work reveals that mating-related traits can be just as important to how organisms ...

Scientists recently made news by using fossil shark scales to reconstruct shark communities from millions of years ago. At the same time, an international team of researchers led by UC Santa Barbara ecologist Erin Dillon applied the technique to the more recent past.

Human activities have caused shark populations to plummet worldwide since records began in the mid-20th century. However, the scientists were concerned that these baseline data may, themselves, reflect shark communities that had already experienced significant declines. Dillon compared the abundance and variety of shark scales from a Panamanian coral reef 7,000 years ago to those in reef sediments ...

A vast seabird colony on Ascension Island creates a "halo" in which fewer fish live, new research shows.

Ascension, a UK Overseas Territory, is home to tens of thousands of seabirds - of various species - whose prey incudes flying fish.

The new study, by the University of Exeter and the Ascension Island Government, finds reduced flying fish numbers up to 150km (more than 90 miles) from the island - which could only be explained by the foraging of seabirds.

The findings - which provide rare evidence for a long-standing theory first proposed at Ascension - show how food-limited seabird populations naturally are, and why they are often so sensitive to competition with human fishers. ...

Nanomaterials found in consumer and health-care products can pass from the bloodstream to the brain side of a blood-brain barrier model with varying ease depending on their shape - creating potential neurological impacts that could be both positive and negative, a new study reveals.

Scientists found that metal-based nanomaterials such as silver and zinc oxide can cross an in vitro model of the 'blood brain barrier' (BBB) as both particles and dissolved ions - adversely affecting the health of astrocyte cells, which control neurological responses.

But the researchers also believe that their discovery will help to design safer nanomaterials and could open ...

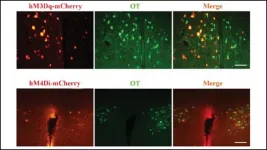

Like female voles, connections between oxytocin neurons in the hypothalamus and dopamine neurons in reward areas drive parental behaviors in male voles, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

Motherhood receives most of the attention in the research world, yet in 5% of mammals -- including humans -- fathers provide care, too. The "love hormone" oxytocin plays a role in paternal care, but the exact neural pathways underlying the behavior were not known.

He et al. measured the neural activity of vole fathers while they interacted with their offspring. Oxytocin neurons connecting the hypothalamus to a reward area fired when the fathers cared for their offspring. ...

The psychedelic drug psilocybin, a naturally occurring compound found in some mushrooms, has been studied as a potential treatment for depression for years. But exactly how it works in the brain and how long beneficial results might last is still unclear.

In a new study, Yale researchers show that a single dose of psilocybin given to mice prompted an immediate and long-lasting increase in connections between neurons. The findings are published July 5 in the journal Neuron.

"We not only saw a 10% increase in the number of neuronal connections, but also they were on average about 10% larger, so the connections were stronger as well," said Yale's Alex Kwan, associate professor of psychiatry and of neuroscience and senior author of the paper.

Previous ...

A new collaborative research led by researchers from the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Ritsumeikan University, and Kyoto University found that although unlimited irrigation could increase global BECCS potential (via the increase of bioenergy production) by 60-71% by the end of this century, sustainably constrained irrigation would increase it by only 5-6%. The study has been published in Nature Sustainability on July 5.

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is a process of extracting bioenergy from biomass, ...