(Press-News.org) A massive explosion from a previously unknown source - 10 times more energetic than a supernova - could be the answer to a 13-billion-year-old Milky Way mystery.

Astronomers led by David Yong, Gary Da Costa and Chiaki Kobayashi from Australia's ARC Centre of Excellence in All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) based at the Australian National University (ANU) have potentially discovered the first evidence of the destruction of a collapsed rapidly spinning star - a phenomenon they describe as a "magneto-rotational hypernova".

The previously unknown type of cataclysm - which occurred barely a billion years after the Big Bang - is the most likely explanation for the presence of unusually high amounts of some elements detected in another extremely ancient and "primitive" Milky Way star.

That star, known as SMSS J200322.54-114203.3, contains larger amounts of metal elements, including zinc, uranium, europium and possibly gold, than others of the same age.

Neutron star mergers - the accepted sources of the material needed to forge them - are not enough to explain their presence.

The astronomers calculate that only the violent collapse of a very early star - amplified by rapid rotation and the presence of a strong magnetic field - can account for the additional neutrons required.

The research is published today in the journal Nature.

"The star we're looking at has an iron-to-hydrogen ratio about 3000 times lower than the Sun - which means it is a very rare: what we call an extremely metal-poor star," said Dr Yong, who is based at the ANU.

"However, the fact that it contains much larger than expected amounts of some heavier elements means that it is even rarer - a real needle in a haystack."

The first stars in the universe were made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium. At length, they collapsed and exploded, turning into neutron stars or black holes, producing heavier elements which became incorporated in tiny amounts into the next generation of stars - the oldest still in existence.

Rates and energies of these star deaths have become well known in recent years, so the amount of heavy elements they produce is well calculated. And, for SMSS J200322.54-114203.3, the sums just don't add up.

"The extra amounts of these elements had to come from somewhere," said Associate Professor Chiaki Kobayashi from the University of Hertfordshire, UK.

"We now find the observational evidence for the first time directly indicating that there was a different kind of hypernova producing all stable elements in the periodic table at once -- a core-collapse explosion of a fast-spinning strongly-magnetized massive star. It is the only thing that explains the results."

Hypernovae have been known since the late 1990s. However, this is the first time one combining both rapid rotation and strong magnetism has been detected.

"It's an explosive death for the star," said Dr Yong. "We calculate that 13 billion-years ago J200322.54-114203.3 formed out of a chemical soup that contained the remains of this type of hypernova. No one's ever found this phenomenon before."

J200322.54-114203.3 lies 7500 light-years from the Sun, and orbits in the halo of the Milky Way.

Another co-author, Nobel Laureate and ANU Vice-Chancellor Professor Brian Schmidt, added, "The high zinc abundance is definite marker of a hypernova, a very energetic supernova."

Head of the First Stars team in ASTRO 3D, Professor Gary Da Costa from ANU, explained that the star was first identified by a project called the SkyMapper survey of the southern sky.

"The star was first identified as extremely metal-poor using SkyMapper and the ANU 2.3m telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in western NSW," he said. "Detailed observations were then obtained with the European Southern Observatory 8m Very Large Telescope in Chile."

ASTRO 3D director, Professor Lisa Kewley, commented: "This is an extremely important discovery that reveals a new pathway for the formation of heavy elements in the infant universe."

Other members of the research team are based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, Stockholm University in Sweden, the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany, Italy's Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, and Australia's University of New South Wales.

INFORMATION:

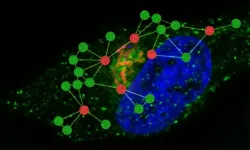

Our cells fight microbial invaders by engulfing them into membrane sacs - hostile environments in which pathogens are rapidly destroyed. However, the pathogen Salmonella enterica, which grows and reproduces inside our cells, has evolved ways to detoxify such hostile compartments, turning them into a comfortable home where Salmonella can survive and thrive.

A team of scientists led by EMBL group leader Nassos Typas has uncovered new details of Salmonella´s survival strategies. The researchers analysed protein interactions in Salmonella-infected cells to identify the diverse biological processes of the host cell that the bacterium uses. Salmonella targets and modifies cellular protein machineries and pathways, ...

Scientists from Trinity College Dublin are homing in on a recipe that would enable the future production of entirely renewable, clean energy from which water would be the only waste product.

Using their expertise in chemistry, theoretical physics and artificial intelligence, the team is now fine-tuning the recipe with the genuine belief that the seemingly impossible will one day be reality.

Initial work in this area, reported just under two years ago, yielded promise. That promise has now been amplified significantly in the exciting work just published in leading journal, Cell Reports Physical Science.

Energy ...

Researchers from North Carolina State University have developed a patch that plants can "wear" to monitor continuously for plant diseases or other stresses, such as crop damage or extreme heat.

"We've created a wearable sensor that monitors plant stress and disease in a noninvasive way by measuring the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by plants," says Qingshan Wei, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work. Wei is an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State.

Current methods of testing for plant stress or disease involve taking plant tissue samples and conducting an assay in a lab. However, this ...

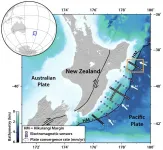

The Hikurangi Margin, located off the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand, is where the Pacific tectonic plate dives underneath the Australian tectonic plate, in what scientists call a subduction zone. This interface of tectonic plates is partly responsible for the more than 15,000 earthquakes the region experiences each year. Most are too small to be noticed, but between 150 and 200 are large enough to be felt. Geological evidence suggests that large earthquakes happened in the southern part of the margin before human record-keeping began.

Geophysicists, geologists, and geochemists from throughout the world have been working together to understand why this plate boundary behaves as it does, producing both imperceptible silent earthquakes, but also potentially major ...

Reston, VA--For patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC), molecular imaging can improve staging and clinical management of the disease, according to research published in the June issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. In a retrospective study of PDAC patients, the addition of PET/CT imaging with 68Ga-FAPI led to restaging of disease in more than half of the patients, most notably in those with local recurrence.

PDAC is a highly lethal cancer, with a five-year survival rate of less than 10 percent. Optimal imaging of PDAC is crucial for accurate initial TNM (tumor, node, metastases) staging and selection ...

Dancing with music can halt most debilitating symptoms of Parkinson's disease

First-of-its-kind York U study shows participating in weekly dance training improves daily living and motor function for those with mild-to-moderate Parkinson's

TORONTO, July 7, 2021 - A new study published in Brain Sciences today, shows patients with mild-to-moderate Parkinson's disease (PD) can slow the progress of the disease by participating in dance training with music for one-and-a-quarter hours per week. Over the course of three years, this activity was found to reduce daily motor issues such as those related to balance and speech, ...

When a head of state or government official travels to another country to meet with his/her counterpart, the high-level visit often entails a range of public diplomacy activities, which aim to increase public support in the host country. These activities often include events such as hosting a joint press conference, attending a reception or dinner, visiting a historic site, or attending a social or sports event. A new study finds that public diplomacy accompanying a high-level visit by a national leader increases public approval in the host country. The findings are published in the American Political ...

The Arctic is warming at approximately twice the global rate. A new study led by researchers from McGill University finds that cold-adapted Arctic species, like the thick-billed murre, are especially vulnerable to heat stress caused by climate change.

"We discovered that murres have the lowest cooling efficiency ever reported in birds, which means they have an extremely poor ability to dissipate or lose heat," says lead author Emily Choy, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Natural Resource Sciences Department at McGill University.

Following reports of the seabirds dying in their nests on sunny days, the researchers trekked the cliffs ...

Data from nine cities in Mexico confirms that identifying dengue fever “hot spots” can provide a predictive map for future outbreaks of Zika and chikungunya. All three of these viral diseases are spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Lancet Planetary Health published the research, led by Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, associate professor in Emory University’s Department of Environmental Sciences. The study provides a risk-stratification method to more effectively guide the control of diseases spread by Aedes aegypti. “Our results can help public health officials to do targeted, proactive interventions ...

Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of death by cancer in Australian men.

Early detection is key to successful treatment but men often dodge the doctor, avoiding diagnosis tests until it's too late.

Now an artificial intelligence (AI) program developed at RMIT University could catch the disease earlier, allowing for incidental detection through routine computed tomography (CT) scans.

The tech, developed in collaboration with clinicians at St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, works by analysing CT scans for tell-tale signs of prostate ...