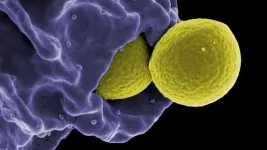

Now, Northwestern has teamed up with the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and Michigan State University (MSU) to reveal that these same sparks fly from highly specialized metal-loaded compartments at the egg surface when frog eggs are fertilized. This means that the early chemistry of conception has evolutionary roots going back at least 300 million years, to the last common ancestor between frogs and people.

"This work may help inform our understanding of the interplay of dietary zinc status and human fertility." -- Thomas O'Halloran, professor, Michigan State University

And the research has implications beyond this shared biology and deep-rooted history. It could also help shape future findings about how metals impact the earliest moments in human development.

"This work may help inform our understanding of the interplay of dietary zinc status and human fertility," said Thomas O'Halloran, the senior author of the research paper published June 21 in the journal Nature Chemistry.

O'Halloran was part of the original zinc spark discovery at Northwestern and, earlier this year, he joined Michigan State as a foundation professor of microbiology and molecular genetics and chemistry. O'Halloran was the founder of Northwestern's Chemistry of Life Processes Institute, or CLP, and remains a member.

The team also discovered that fertilized frog eggs eject another metal, manganese, in addition to zinc. It appears these ejected manganese ions collide with sperm surrounding the fertilized egg and prevent them from entering.

"These breakthroughs support an emerging picture that transition metals are used by cells to regulate some of the earliest decisions in the life of an organism," O'Halloran said.

To make these discoveries, the team needed access to some of the most powerful microscopes in the world as well as expertise that spanned chemistry, biology and X-ray physics. That unique combination included collaborators at the Center for Quantitative Element Mapping for the Life Sciences, or QE-Map, an interdisciplinary National Institutes of Health-funded research hub at MSU and Northwestern's CLP. The research relied heavily on the tools and expertise available at Argonne.

The research team brought sections of frog eggs and embryos to Argonne for analysis. Using both X-ray and electron microscopy, the researchers determined the identity, concentrations and intracellular distributions of metals both before and after fertilization.

X-ray fluorescence microscopy was conducted at beamline 2-ID-D of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Argonne. Barry Lai, group leader at Argonne and an author on the paper, said that the X-ray analysis quantified the amount of zinc, manganese and other metals concentrated in small pockets around the outer layer of the eggs. They found these pockets contained more than 30 times the manganese as the rest of the eggs, and 10 times the zinc.

"We are able to do this analysis because of the elemental sensitivity of the beamline," Lai said. "In fact, it is so sensitive that substantially lower concentrations can be measured."

Complementary scans were conducted using transmission electron microscopy at the Center for Nanoscale Materials (CNM), a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Argonne. Further analysis was performed on a separate prototype scanning transmission electron microscope that includes technology developed by Argonne Senior Scientist Nestor Zaluzec, an author on the paper. These scans were performed at smaller scales -- down to a few nanometers, about 100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair -- but found the same results: high concentrations of metals in pockets around the outer layer.

Both X-ray and electron microscopy showed that the metals in these pockets were almost completely released after fertilization.

"Argonne has the tools necessary to examine these biological samples at these scales without destroying them with X-rays or electrons," Zaluzec said. "It's a combination of the right resources and the right expertise."

The APS is in the process of undergoing a massive upgrade, one that will increase the brightness of its X-ray beams by up to 500 times. Lai said that an upgraded APS could complete these scans much more quickly or with higher spatial resolution. What took more than an hour for this research could be done in less than one minute after the upgrade, Lai said.

"We often think of genes as key regulating factors, but our work has shown that atoms like zinc and manganese are critical to the first steps in development after fertilization," said MSU Provost Teresa K. Woodruff, Ph.D., another senior author on the paper.

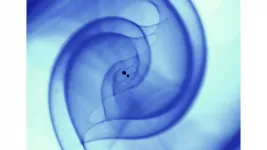

Woodruff, an MSU foundation professor and former member of CLP, was also a leader of the Northwestern team that discovered zinc sparks five years ago. With the discovery of manganese sparks in African clawed frogs, or Xenopus laevis, the team is excited to explore whether the element is released by human eggs when fertilized.

"These discoveries could only be made by interdisciplinary groups, fearlessly looking into fundamental steps," she said. "Working across disciplines at the literal edge of technology is one of the most profound ways new discoveries take place."

"Xenopus is a perfect system for such studies because their eggs are an order of magnitude larger than human or mouse eggs, and are accessible in large numbers " said Carole LaBonne, another senior author on the study, CLP member, and chair of the Department of Molecular Biosciences at Northwestern. "The discovery of zinc and manganese sparks is exciting, and suggests there may be other fundamental signaling roles for these transition metals."

INFORMATION:

About Argonne's Center for Nanoscale Materials The Center for Nanoscale Materials is one of the five DOE Nanoscale Science Research Centers, premier national user facilities for interdisciplinary research at the nanoscale supported by the DOE Office of Science. Together the NSRCs comprise a suite of complementary facilities that provide researchers with state-of-the-art capabilities to fabricate, process, characterize and model nanoscale materials, and constitute the largest infrastructure investment of the National Nanotechnology Initiative. The NSRCs are located at DOE's Argonne, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley, Oak Ridge, Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratories. For more information about the DOE NSRCs, please visit https://science.osti.gov/User-Facilities/User-Facilities-at-a-Glance.

About the Advanced Photon Source

The U. S. Department of Energy Office of Science's Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world's most productive X-ray light source facilities. The APS provides high-brightness X-ray beams to a diverse community of researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. These X-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation's economic, technological, and physical well-being. Each year, more than 5,000 researchers use the APS to produce over 2,000 publications detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other X-ray light source research facility. APS scientists and engineers innovate technology that is at the heart of advancing accelerator and light-source operations. This includes the insertion devices that produce extreme-brightness X-rays prized by researchers, lenses that focus the X-rays down to a few nanometers, instrumentation that maximizes the way the X-rays interact with samples being studied, and software that gathers and manages the massive quantity of data resulting from discovery research at the APS.

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.