(Press-News.org) July 12, 2021-- A new study sheds light on how the specter of dementia and chronic pain reduce people's desire to live into older ages. Among Norwegians 60 years of age and older the desire to live into advanced ages was significantly reduced by hypothetical adverse life scenarios with the strongest effect caused by dementia and chronic pain, according to research conducted at the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center based at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

The paper is among the first to study Preferred Life Expectancy (PLE) based on hypothetical health and living conditions. The findings are published in the July issue of the journal Age and Ageing.

The research team was led by Vegard Skirbekk, PhD, professor of Population and Family Health, who used data from Norway, because of its relatively high life expectancy at birth. He investigated how six adverse health and living conditions affected PLE after the age of 60 and assessed each by age, sex, education, marital status, cognitive function, self-reported loneliness and chronic pain.

The analysis included data from the population-based NORSE-Oppland County study of health and living conditions based on a representative sample of the population aged 60-69 years, 70-79 years and 80 years and older. The data collection was done in three waves in 2017, 2018 and 2019. A total of 948 individuals participated in the interviews and health examinations.

Skirbekk and colleagues asked the 825 community dwellers aged 60 and older the question, "If you could choose freely, until which age would you wish to live?" The results showed that among Norwegians over 60, the desire to live into advanced ages was significantly reduced by hypothetical adverse life scenarios, such as effects of dementia and chronic pain. Weaker negative PLE effects were found for the prospect of losing one's spouse or being subject to poverty

According to Skirbekk, "Dementia tops the list of conditions where people would prefer to live shorter lives - which is a particular challenge given the rapid increase in dementia in the years ahead."

The average Preferred Life Expectancy was 91.4 years of age and there was no difference between men and women, but older participants had higher PLE than younger participants. PLE among singles was not affected by the prospect of feeling lonely. The higher educated had lower PLE for dementia and chronic pain.

"Despite the fact that rising life expectancy to a large extent occurs at later ages, where the experience of loss and disability are widespread, there had been remarkably little scientific evidence on how long individuals would like to live given the impact of such adverse life conditions,' noted Skirbekk.

INFORMATION:

Other authors are Ellen Melby Langballe, Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Norway; and Bjørn Heine Strand, Norwegian Institute of Public Health and

Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Norway.

The study was supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence, project number 262700.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Founded in 1922, the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health pursues an agenda of research, education, and service to address the critical and complex public health issues affecting New Yorkers, the nation and the world. The Columbia Mailman School is the seventh largest recipient of NIH grants among schools of public health. Its nearly 300 multi-disciplinary faculty members work in more than 100 countries around the world, addressing such issues as preventing infectious and chronic diseases, environmental health, maternal and child health, health policy, climate change and health, and public health preparedness. It is a leader in public health education with more than 1,300 graduate students from 55 nations pursuing a variety of master's and doctoral degree programs. The Columbia Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers, including ICAP and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit http://www.mailman.columbia.edu.

A new University of Arizona Health Sciences study found women on hormone therapy were up to 58% less likely to develop neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease, and reduction of risk varied by type and route of hormone therapy and duration of use. The findings could lead to the development of a precision medicine approach to preventing neurodegenerative diseases.

The study, published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, found that women who underwent menopausal hormone therapy for six years or greater were 79% less likely to ...

A team of researchers at the University of Cambridge has developed a new experimental and theoretical platform to study how viruses evolve while spreading within an organism.

In the study, published in PHYSICAL REVIEW X, the researchers used experimental data and simulations of a phage-bacteria ecosystem to uncover that viral expansions can transition from 'pulled' - where the expansion is led by the pioneering viral particles at the very edge of the population, to 'pushed', where the expansion is driven by viruses arising behind the front and within the infected region.

Crucially, pushed waves are known ...

Commonly-used household products should carry a warning that they increase the risk of asthma, according to a new evidence review.

New research conducted by Smartline, a research project funded by the European Regional Development Fund, finds evidence that a group of chemicals found in a wide range of products in people's homes increases the risk of asthma. Authors conclude that labelling should reflect this risk, and warn people to ventilate their homes while using them.

The research reviewed 12 studies into Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), which are emitted as gases from certain solids or liquids. VOCs are emitted by a wide array of products, including some that are widely used as ingredients in household products. ...

The city park may be an artificial ecosystem but it plays a key role in the environment and our health, the first global assessment of the microbiome in city parks has found.

The study, published in END ...

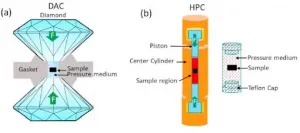

The discovery of iron-based superconductors with a relatively high transition temperature Tc in 2008 opened a new chapter in the development of high-temperature superconductivity.

The following decade saw a 'research boom' in superconductivity, with remarkable achievements in the theory, experiments and applications of iron-based superconductors, and in our understanding of the fundamental mechanism of superconductivity.

A UOW paper published last month reviews progress on high-pressure studies on properties of iron-based superconductor (ISBC) families.

FLEET PhD student Lina Sang (University of Wollongong) was first author on the Materials Today Physics review paper, investigating ...

Movies and television often show romance sparking when two strangers meet. Real-life couples, however, are far more likely to begin as friends. Two-thirds of romantic relationships start out platonically, a new study in Social Psychological and Personality Science finds.

This friends-first initiation of romance is often overlooked by researchers. Examining a sample of previous studies on how relationships begin, the authors found that nearly 75 percent focused on the spark of romance between strangers. Only eight percent centered on romance that develops among friends over time.

"There are a lot of people ...

Destroying tropical ecosystems and replacing them with soybeans and other crops has immediate and devastating consequences for soybeans, according to new peer-reviewed research in the journal World Development. With 35.8 million hectare currently under soy cultivation in Brazil, extreme heat--which adjacent tropical forests help keep in check--has reduced soybean income by an average of approximately US$100 per hectare per year.

The study, Conserving the Cerrado and Amazon biomes of Brazil protects the soy economy from damaging warming, shows that protecting the Amazon and Cerrado can prevent the sort of high temperatures that damages the productivity of crops--estimated to cost the sector US$3.55 billion.

Another recent study found annual agricultural losses associated ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - After cutbacks and layoffs, remaining employees were more likely to feel they were treated fairly if the companies invested in them - and morale was less likely to plunge, according to new research.

Those investments can include training for workers, team-building exercises or improving company culture. Even keeping workloads manageable after layoffs can help employees' job attitudes, according to the Journal of Organizational Behavior study.

"Whenever possible, cost-cutting is best combined with signals that people remain the firm's most prized asset," said Jeff Joireman, the study's co-author and a professor in Washington State University's Carson College of Business.

Researchers reviewed 137 previous studies examining job attitudes before, during and after cost-cutting ...

If we pay closer attention to how birds, rabbits and termites transform their local living spaces in response to varying climate conditions, we could become much better at predicting what impact climate change will have on them in future.

This is according to a group of researchers* from the Universities of Montana and Wyoming in the United States, the University of Tours in France and Stellenbosch University (SU) in South Africa. They examined how animals' ability to respond to climate change likely depends on how well they modify their habitats, such as the way they build nests and burrows.

The findings of their study were published recently in the high-impact journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

"It's crucial that we continuously improve our ability to predict and mitigate the ...

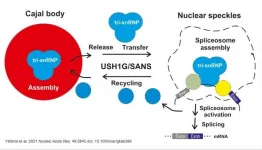

Human Usher syndrome (USH) is the most common form of hereditary deaf-blindness. Sufferers can be deaf from birth, suffer from balance disorders, and eventually lose their eyesight as the disease progresses. For some 25 years now, the research group led by Professor Uwe Wolfrum of the Institute of Molecular Physiology at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) has been conducting research into Usher syndrome. Working in cooperation with the group headed up by Professor Reinhard Lührmann at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, his team has now identified a novel pathomechanism leading to Usher syndrome. They have discovered that the Usher syndrome type 1G protein SANS plays a crucial role in regulating ...