INFORMATION:

* Source: Woods, HA; Pincebourde, S; Dillon, ME; & Terblanche, JS 2021. Extended phenotypes: buffers or amplifiers of climate change? Trends in Ecology and Evolution: doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.05.010 1

*Art Woods (University of Montana), Sylvain Pincebourde (University of Tours), Michael Dillon (University of Wyoming) and John Terblanche (Stellenbosch University).

Humans can learn from animals and insects about impact of climate change

Crucial that we continuously improve our ability to predict and mitigate the effects of climate change

2021-07-12

(Press-News.org) If we pay closer attention to how birds, rabbits and termites transform their local living spaces in response to varying climate conditions, we could become much better at predicting what impact climate change will have on them in future.

This is according to a group of researchers* from the Universities of Montana and Wyoming in the United States, the University of Tours in France and Stellenbosch University (SU) in South Africa. They examined how animals' ability to respond to climate change likely depends on how well they modify their habitats, such as the way they build nests and burrows.

The findings of their study were published recently in the high-impact journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

"It's crucial that we continuously improve our ability to predict and mitigate the effects of climate change. One of the ways we can do this is by gaining a better understanding of how animals influence their own small-scale experience of climate at the level of individual members in a population," says one of the researchers, Prof John Terblanche from SU's Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology.

Terblanche and his co-authors mention that in order to enhance the predictive power of typical contemporary climate change models, it will be important for biologists to understand how animals transform their living space locally in response to climate variability.

"Improving such models will be key to forecasting the effects of climate change on species, and to predict future effects, including how species ranges may shift and what the relative risks of extinction are for different animal species with high levels of precision."

They add that knowing which species will proliferate with climate change is central to understanding pest outbreaks on crops, or disease vectors changing risks for humans.

"Climate change will impact the spread of disease vectors, the health of marine and terrestrial biomes around the world and will influence whether agriculture and fishing will be able to continue supporting human populations, as they have in the past."

In their study, the researchers point out how some animals have found unique ways to protect themselves against extreme climate conditions.

"Many animals dig burrows, construct nests for themselves or their offspring, build homes for entire colonies (ants and termites), induce plants to produce galls, build leaf mines, or simply modify the structure or texture of their local environments.

"For example, birds build nests to keep eggs and chicks warm during cool weather, but also make adjustments in nest insulation to keep the little ones cool in very hot conditions. Mammals, such as rabbits or mice, sleep or hibernate in underground burrows that provide stable, moderate temperatures and avoid above-ground conditions that often are far more extreme outside the burrow.

"We've also seen how termites and ants build mounds that capture wind and solar energy to drive airflow through the colony, which stabilizes temperature, relative humidity, and oxygen level experienced by the colony."

The researchers say these modifications, known as extended phenotypes, filter climate into local sets of conditions immediately around the organism - 'the microclimate', which is key for a better understanding of the impact of climate change.

"Two features of microclimates are important. First, microclimates typically differ strongly from nearby climates, which means that the climate in an area may provide little information about what animals experience in their microhabitats. Second, because extended phenotypes are built structures, they often are modified in response to local climate variation, and potentially in response to climate change."

The researchers call for a renewed effort to understand how extended phenotypes mediate how organisms experience climate change. "We need a much better understanding of how much animals can adjust these structures in response to varying climate conditions," says Terblanche.

"Another key challenge is to understand how much flexibility there is in extended phenotypes, and how rapidly they can evolve. At this point, we pretty much have no idea whether these processes can keep up with climate change," adds lead author Art Woods from the University of Montana.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

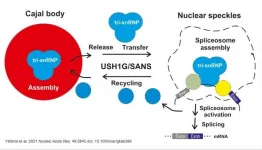

Remarkable new insights into the pathology of Usher syndrome

2021-07-12

Human Usher syndrome (USH) is the most common form of hereditary deaf-blindness. Sufferers can be deaf from birth, suffer from balance disorders, and eventually lose their eyesight as the disease progresses. For some 25 years now, the research group led by Professor Uwe Wolfrum of the Institute of Molecular Physiology at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) has been conducting research into Usher syndrome. Working in cooperation with the group headed up by Professor Reinhard Lührmann at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, his team has now identified a novel pathomechanism leading to Usher syndrome. They have discovered that the Usher syndrome type 1G protein SANS plays a crucial role in regulating ...

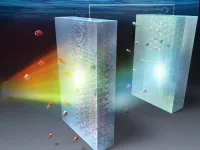

Giving a "tandem" boost to solar-powered water splitting

2021-07-12

Turning away from fossil fuels is necessary if we are to avert an environmental crisis due to global warming. Both industry and academia have been focusing heavily on hydrogen as a feasible clean alternative. Hydrogen is practically inexhaustible and when used to generate energy, only produces water vapor. However, to realize a truly eco-friendly hydrogen society, we need to be able to mass-produce hydrogen cleanly in the first place.

One way to do that is by splitting water via "artificial photosynthesis," a process in which materials called "photocatalysts" leverage solar energy to produce oxygen and hydrogen from water. However, the available photocatalysts are not yet where they need to be to make solar-powered water splitting economically feasible and scalable. ...

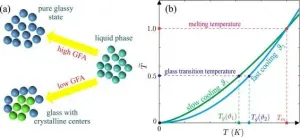

Theoretical model able to reliably predict low-temperature properties of compounds

2021-07-12

Co-authors Bulat Galimzyanov and Anatolii Mokshin (Department of Computational Physics) have developed a unique model that allows for a universal interpretation of experimental data on viscosity for systems of different types, while also proposing an alternative method for classifying materials based on a unified temperature scale.

The publication was funded by Russian Science Foundation's grant 'Theoretical, simulation and experimental studies of physical and mechanical features of amorphous systems with inhomogeneous local viscoelastic properties', guided by Professor Mokshin.

Using the developed viscosity model, scientists processed experimental data obtained for thirty different ...

Study sheds light on precise personalized hepatocellular carcinoma medicine

2021-07-12

A research group led by Prof. PIAO Hailong from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) identified hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) subtypes with distinctive metabolic phenotypes through bioinformatics and machine learning methods, and elucidated the potential mechanisms based on a metabolite-protein interaction network and multi-omics data.

The study, published in Advanced Science on July 11, provides insights guiding precise personalized HCC medicine.

Metabolic reprogramming, which can promote rapid cell proliferation by regulating energy and nutrient metabolism, is considered to be one hallmark of cancer. It can impact other biological processes through complex metabolite-protein ...

Want to avoid running overuse injuries? Don't lean forward so much, says CU Denver study

2021-07-12

The ubiquitous overuse injuries that nag runners may stem from an unlikely culprit: how far you lean forward.

Trunk flexion, the angle at which a runner bends forward from the hip, can range wildly--runners have self-reported angles of approximately -2 degrees to upward of 25. A new study from the END ...

Heart risk 'calculators' overlook increased risk for people of South Asian ancestry

2021-07-12

DALLAS, July 12, 2021 -- People of South Asian ancestry have more than double the risk of developing heart disease compared to people of European ancestry, yet clinical risk assessment calculators used to guide decisions about preventing or treating heart disease may fail to account for the increased risk, according to new research published today in the American Heart Association's flagship journal Circulation.

About a quarter of the world's population (1.8 billion people) are of South Asian descent, and prior research has shown South Asians experience higher rates of heart disease compared to people of most other ethnicities.

To better understand the variables surrounding the heart disease risk for people of South Asian ancestry, researchers evaluated ...

Innovative gene therapy 'reprograms' cells to reverse neurological deficiencies

2021-07-12

A novel method of gene therapy is helping children born with a rare genetic disorder called AADC deficiency that causes severe physical and developmental disabilities. The study, led by researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and The Ohio State University College of Medicine, offers new hope to those living with incurable genetic and neurodegenerative diseases.

Research findings are published online in the journal Nature Communications.

This study describes the findings from the targeted delivery of gene therapy to midbrain to treat a rare ...

USC researchers discover better way to identify DNA variants

2021-07-12

USC researchers have achieved a better way to identify elusive DNA variants responsible for genetic changes affecting cell functions and diseases.

Using computational biology tools, scientists at the university's Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences studied "variable-number tandem repeats" (VNTR) in DNA. VNTRs are stretches of DNA made of a short pattern of nucleotides repeated over and over, like a plaid pattern shirt. Though they comprise but 3% of the human genome, the repetitive DNA governs how some genes are encoded and levels of proteins are produced in a cell, and account for most of the structural variation.

Current methods do not accurately detect the variations in genes in some repetitive ...

Scientists blueprint bacterial enzyme believed to "stealthily" suppress immune response

2021-07-12

Scientists have produced the first fine-detail molecular blueprints of a bacterial enzyme known as Lit, which is suspected to play a "stealthy" role in the progression of infection by reducing the immune response.

Blueprints such as these allow drug designers to uncover potential weaknesses in bacterial arsenals as they seek to develop new therapeutics that may help us win the war against antibiotic resistance.

The study, led by scientists from the School of Biochemistry and Immunology and the Trinity Biomedical Sciences Institute (TBSI) at Trinity College Dublin, has just been published by leading international journal Nature Communications.

Lipoproteins and their role in ...

A Trojan horse could help get drugs past our brain's tough border patrol

2021-07-12

Sclerosis, Parkinson's Disease, Alzheimer's and epilepsy are but a few of the central nervous system disorders. They are also very difficult to treat, since the brain is protected by the blood-brain barrier.

The blood-brain barrier works as a border wall between the blood and the brain, allowing just certain molecules to enter the brain. And whereas water and oxygen can get through, as can other substances such as alcohol and coffee. But it does block more than 99 percent of potentially neuroprotective compounds from reaching their targets in the brain.

Now, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

[Press-News.org] Humans can learn from animals and insects about impact of climate changeCrucial that we continuously improve our ability to predict and mitigate the effects of climate change