(Press-News.org) Butterflies and moths have beautiful wings: the bright flare of an orange monarch, the vivid stripes of a swallowtail, the luminous green of a Luna moth. But some butterflies flutter on even more dramatic wings: parts of their wing, or sometimes the entire wing itself, are actually transparent.

Many aquatic organisms, including jellies and fish, are transparent. But transparent butterfly and moth wings are so arresting that merely catching a glimpse of one typically causes a human to lunge for a camera or at least point it out to their friends. These enigmatic, transparent butterfly wings have not been studied comprehensively.

Doris Gomez and Marianne Elias (French National Center for Scientific Research) set out to change that. Last week, along with a multidisciplinary team of ecologists, biologists and physicists, they published a massive survey on the optics and ecological implications of moths and butterflies with transparent wings in the Ecological Society of America's journal Ecological Monographs. They discovered that transparency has evolved in Lepidoptera more than once, and that there are many ways to be transparent.

Gomez, an ecologist who has studied the physics and ecological aspects of iridescence in hummingbird wings and other bird coloration, was intrigued by these so-called "glasswing" butterflies and moths when she met Elias, an evolutionary biologist who worked on the ecology and evolution of the tropical butterflies Ithomiini, which have transparent wings. Gomez was startled to find that almost nothing had been written about transparency in Lepidoptera, nor in any other terrestrial animal.

"This paper is a breakthrough because everything that's been known so far on transparency was about aquatic organisms," Gomez said. "Transparency is so rare in terrestrial organisms that people never bothered to study it comprehensively."

She and her team analyzed 123 species of Lepidoptera from samples in the French Museum of Natural History's collection. They found transparency, or "clearwing" species, in 31 out of 124 families. But not all species accomplish transparency in the same way. They examined the extent to which transparency affects thermoregulation and provides protection against ultraviolet radiation.

Many insects, including wasps, flies and dragonflies, have clear wings. Their wings consist of a transparent membrane made of chitin. Butterfly and moth wings are made of the same kind of transparent membrane, but in most cases moths and butterflies have opaque scales obscuring the membrane. The scales are what are responsible for their mesmerizing patterns and coloration.

Gomez and her team discovered that clearwing species have a number of ways to make their wings transparent. Some transparent moths and butterflies have no scales on their wings at all, leaving the chitin membrane to show through. Many other species do have scales, which can be transparent, upright, narrow or hair-like, allowing light through the wing.

Physicists have studied instances of transparency in individual species or genera, in the hopes of understanding the physics of how to adapt biological concepts to make people, vehicles and even structures invisible or transparent. But before now, no one had appreciated the wealth of approaches lepidopterans can take to achieve transparency, or the fact that it has evolved multiple times in different groups.

"This is the first comparative analysis of transparent butterfly wings," said Elias. "What is notable is that transparency has evolved several times independently. But the way the wings become transparent can be dramatically different, from highly packed transparent scales to the mere absence of scales, through scale reduction in size and density. There are many ways of being transparent. We don't know why this diversity exists."

In some cases, different strategies lead to the same level of transparency, leaving researchers pondering why such diversity exists at all. They theorize that transparency may be beneficial in different ways for different species, including as camouflage or to mimic wasp and bees. Transparency also seems to help moths and butterflies regulate their body temperature, but does not protect them from UV radiation.

Gomez, who has a passion for working with scientists from across other disciplines, included physicists in the study to explore the optical properties of the wings including discerning what birds, their would-be predators, see when they look at a transparent butterfly. They found that the more light that can pass through a wing - i.e., the more transparent it is - the less visible the butterfly is to predators. Transparency acts like the ultimate camouflage.

Like the butterflies themselves, the results are compelling. However, the scientists emphasize that the study has raised more questions and avenues of exploration to continue to uncover the evolutionary role and ecological implications of transparency.

"Butterflies are such iconic organisms," said Gomez. "They're so wonderful to study. I like to study complex concepts, like iridescence and transparency because there is so much to explore - and it's so easy to get everyone excited about them."

INFORMATION:

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world's largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes five journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society's Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.

ESA is offering complimentary registration at the 106th Annual Meeting of the Ecological Society of America for press and institutional public information officers (see credential policy). The meeting will feature live plenaries, panels and Q&A sessions from August 2-6, 2021. To apply for press registration, please contact ESA Public Information Manager Heidi Swanson at heidi@esa.org.

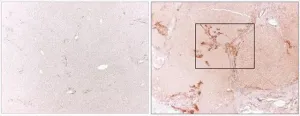

Chronic alcohol abuse and hepatitis can injure the liver and lead to fibrosis, the buildup of collagen and scar tissue. As a potential approach to treating liver fibrosis, University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers and their collaborators are looking for ways to stop liver cells from producing collagen.

"So we thought...what if we take immunotoxins and try to get them to kill collagen-producing cells in the liver," said team lead Tatiana Kisseleva, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine. "If these antibodies carrying toxic molecules can find and bind the cells, the cells will eat up the 'gift' and die."

In a study published July 12, 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Kisseleva ...

Having a home near a busy airport certainly has its perks. It is close to many establishments and alleviates the problem of wading through endless traffic to catch flights. But it does come at a cost -- tolerating the jarring sounds of commercial airplanes during landing and takeoff.

Researchers at Texas A&M University have conducted a computational study that validates using a shape-memory alloy to reduce the unpleasant plane noise produced during landing. They noted that these materials could be inserted as passive, seamless fillers within airplane wings ...

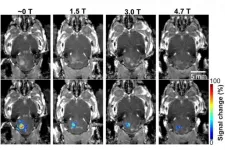

MRI-guided focused ultrasound combined with microbubbles can open the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and allow therapeutic drugs to reach the diseased brain location under the guidance of MRI. It is a promising technique that has been shown safe in patients with various brain diseases, such as Alzheimer's diseases, Parkinson's disease, ALS, and glioblastoma. While MRI has been commonly used for treatment guidance and assessment in preclinical research and clinical studies, until now, researchers did not know the impact of the static magnetic field generated by the MRI scanner on the BBB opening size and ...

Children with a devastating genetic disorder characterized by severe motor disability and developmental delay have experienced sometimes dramatic improvements in a gene therapy trial launched at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals.

The trial includes seven children aged 4 to 9 born with deficiency of AADC, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, that leaves them unable to speak, feed themselves or hold up their head. Six of the children were treated at UCSF and one at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

Children in the study experienced improved motor function, better mood, and longer sleep, and were able to interact more fully with their ...

Historically, shared resources such as forests, fishery stocks, and pasture lands have often been managed with an aim toward averting "tragedies of the commons," which are thought to result from selfish overuse. Writing in BioScience, Drs. Senay Yitbarek (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Karen Bailey (University of Colorado Boulder), Nyeema Harris (Yale University), and colleagues critique this model, arguing that, all too often, such conservation has failed to acknowledge the complex socioecological interactions that undergird the health of resource ...

Learning changes the brain, but when learning Braille different brain regions strengthen their connections at varied rates and time frames. A new study published in JNeurosci highlights the dynamic nature of learning-induced brain plasticity.

Learning new skills alters the brain's white matter, the nerve fibers connecting brain regions. When people learn to read tactile Braille, their somatosensory and visual cortices reorganize to accommodate the new demands. Prior studies only examined white matter before and after training, so the exact time course of the changes was not known.

Molendowska and Matuszewski et al. used diffusion MRI to measure changes in the white matter strength of sighted adults as they learned Braille over the course of eight months. They took measurements ...

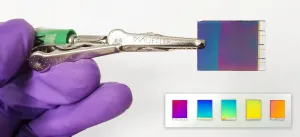

Imagine sitting out in the sun, reading a digital screen as thin as paper, but seeing the same image quality as if you were indoors. Thanks to research from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, it could soon be a reality. A new type of reflective screen - sometimes described as 'electronic paper' - offers optimal colour display, while using ambient light to keep energy consumption to a minimum.

Traditional digital screens use a backlight to illuminate the text or images displayed upon them. This is fine indoors, but we've all experienced the difficulties of viewing such screens in bright sunshine. Reflective screens, however, attempt to use the ambient light, mimicking the way our eyes respond to natural paper.

"For reflective screens to compete with the energy-intensive ...

Smoking among young teens has become an increasingly challenging and costly public healthcare issue. Despite legislation to prevent the marketing of tobacco products to children, tobacco companies have shrewdly adapted their advertising tactics to circumvent the ban and maintain their access to this impressionable--and growing--market share.

How they do it is the subject of a recent study led by Dr. Yael Bar-Zeev at Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU)'s Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine at HU-Hadassah Medical Center. She also serves as Chair of the Israeli Association for Smoking Cessation and Prevention, and teamed up with colleagues at HU and George Washington University. They published their findings in Nicotine and Tobacco Research.

Their study ...

July 12, 2021 - Transitions between healthcare sites - such as from the hospital to home or to a skilled nursing facility - carry known risks to patient safety. Many programs have attempted to improve continuity of care during transitions, but it remains difficult to establish and compare the benefits of these complex interventions. An update on patient-centered approaches to transitional care research and implementation is presented in a supplement to the August issue of Medical Care, sponsored by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Medical Care is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters ...

North Carolina State University researchers have developed a new technique that can alter plant metabolism. Tested in tobacco plants, the technique showed that it could reduce harmful chemical compounds, including some that are carcinogenic. The findings could be used to improve the health benefits of crops.

"A number of techniques can be used to successfully reduce specific chemical compounds, or alkaloids, in plants such as tobacco, but research has shown that some of these techniques can increase other harmful chemical compounds while reducing the target compound," said De-Yu Xie, professor of plant and microbial biology at NC State and the corresponding author of a paper describing the research. "Our technology ...