(Press-News.org) Children with a devastating genetic disorder characterized by severe motor disability and developmental delay have experienced sometimes dramatic improvements in a gene therapy trial launched at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals.

The trial includes seven children aged 4 to 9 born with deficiency of AADC, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, that leaves them unable to speak, feed themselves or hold up their head. Six of the children were treated at UCSF and one at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

Children in the study experienced improved motor function, better mood, and longer sleep, and were able to interact more fully with their parents and siblings. Oculogyric crisis, a hallmark of the disorder involving involuntary upward fixed gaze that may last for hours and may be accompanied by seizure-like episodes, ceased in all but one patient. Results appear July 12, 2021, in Nature Communications.

Just 135 children worldwide are known to be missing the AADC enzyme, with the condition affecting more people of Asian descent.

The trial borrowed from gene delivery techniques used to treat Parkinson's disease, pioneered by senior author Krystof Bankiewicz, MD, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Neurological Surgery and the Weil Institute for Neurosciences, and of the Department of Neurological Surgery at Ohio State University. Both conditions are associated with deficiencies of AADC, which converts levodopa into dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in movement, mood, learning and concentration.

Viral Vector, Real-Time MR Imaging Key to Success

In treating both conditions, Bankiewicz developed a viral vector containing the AADC gene. The vector is infused into the brain via a small hole in the skull, using real-time MR imaging to enable the neurosurgeon to map the target region and plan canula insertion and infusion.

"Children with primary AADC deficiency lack a functional copy of the gene, but we had presumed that their actual neuronal pathway was intact," said co-first author Nalin Gupta, MD, PhD, of the UCSF Department of Neurological Surgery and the surgical principal investigator. "This is unlike Parkinson's disease, where the neurons that produce dopamine undergo degeneration."

While the Parkinson's trial focused on the putamen, a part of the brain that plays a key role in this degeneration, Gupta said the AADC gene therapy trial targeted neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the brainstem, sites that may have more therapeutic benefits.

"The approach for treating AADC deficiency is much more straightforward than it is for Parkinson's," said Bankiewicz. "In AADC deficiency, the wiring of the brain is normal, it's just the neurons don't know how to produce dopamine because they lack AADC."

Physicians who follow patients with AADC deficiency agree that it is usually treated with limited success by managing symptoms, such as with medications used for Parkinson's disease to increase dopamine, melatonin for sleep disturbances and benzodiazepines to relieve oculogyric crisis.

Following gene delivery, PET imaging demonstrated increased brain AADC activity and screening of neurotransmitter metabolites from cerebrospinal fluid showed elevated concentrations, the researchers noted.

At the start of the study, only two of the seven children had partial head control, just one could reach or grasp and none were able to sit independently. Six of the seven were described as irritable and all but one had insomnia. Their baseline motor skill scores were all within the severe impairment range. Symptoms eased after surgery, starting with oculogyric crisis.

"Remarkably, these episodes were the first to disappear and they never returned," said Bankiewicz. "In the months that followed, many patients experienced life-changing improvements. Not only did they begin laughing and have improved mood, but some were able to start speaking and even walking."

New Goals Reached in Sitting, Walking, Feeding, Speech

All patients experienced recognizable gains in motor function, manifested by increased tone and better head and trunk control, and purposeful limb movements. Head control was attained by six of the seven children by month 12 and four were able to sit independently by this time. Also, at 12 months, three patients could reach and grasp and two were able to walk with trunk support. Two-and-a-half years after surgery, one patient started to take independent steps. One patient was able to speak using a vocabulary of about 50 single words by 12 months and a second was able to communicate with an assistive device between 12 to 18 months after gene delivery.

Significant improvements were reported by parents and caregivers in sleep and mood, as well as in feeding difficulties, such as vomiting, and upper airway obstruction due to profuse mucus secretions and congestion. The procedure was well tolerated without adverse short-term or long-term effects, but one child died at seven months after surgery. The patient appeared to be in good health and the cause of death is "most likely attributable to the underlying primary disease," the researchers stated.

The study follows the Parkinson's trial, which also showed positive results with increased durations of well-controlled symptoms. The Bankiewicz team will start two new gene therapy trials, using the same surgical techniques and viral vector, for early Alzheimer's disease and for multiple system atrophy, a rare neurodegenerative disorder. Both trials will run at Ohio State University and will start next month.

INFORMATION:

Co-first author is Toni Pearson, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine and UCSF. Co-authors are from UCSF, Medical Neurogenetics Laboratories, St. Louis Children's Hospital, Ohio State University and Nationwide Children's Hospital. For a full list of authors and disclosures, see the published study.

The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, AADC Research Trust, Pediatric Neurotransmitter Disease Association and Ohio State University.

About UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals

UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals are two leading Bay Area children's hospitals with longstanding commitments to public service. UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital San Francisco and UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital Oakland both have leading pediatric residency programs, unique pediatric subspecialty fellowship programs, a research base for the next generation of discoveries, and expertise in pediatric clinical care, public policy and patient advocacy.

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

Historically, shared resources such as forests, fishery stocks, and pasture lands have often been managed with an aim toward averting "tragedies of the commons," which are thought to result from selfish overuse. Writing in BioScience, Drs. Senay Yitbarek (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Karen Bailey (University of Colorado Boulder), Nyeema Harris (Yale University), and colleagues critique this model, arguing that, all too often, such conservation has failed to acknowledge the complex socioecological interactions that undergird the health of resource ...

Learning changes the brain, but when learning Braille different brain regions strengthen their connections at varied rates and time frames. A new study published in JNeurosci highlights the dynamic nature of learning-induced brain plasticity.

Learning new skills alters the brain's white matter, the nerve fibers connecting brain regions. When people learn to read tactile Braille, their somatosensory and visual cortices reorganize to accommodate the new demands. Prior studies only examined white matter before and after training, so the exact time course of the changes was not known.

Molendowska and Matuszewski et al. used diffusion MRI to measure changes in the white matter strength of sighted adults as they learned Braille over the course of eight months. They took measurements ...

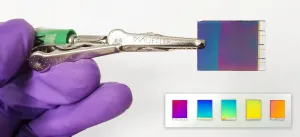

Imagine sitting out in the sun, reading a digital screen as thin as paper, but seeing the same image quality as if you were indoors. Thanks to research from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, it could soon be a reality. A new type of reflective screen - sometimes described as 'electronic paper' - offers optimal colour display, while using ambient light to keep energy consumption to a minimum.

Traditional digital screens use a backlight to illuminate the text or images displayed upon them. This is fine indoors, but we've all experienced the difficulties of viewing such screens in bright sunshine. Reflective screens, however, attempt to use the ambient light, mimicking the way our eyes respond to natural paper.

"For reflective screens to compete with the energy-intensive ...

Smoking among young teens has become an increasingly challenging and costly public healthcare issue. Despite legislation to prevent the marketing of tobacco products to children, tobacco companies have shrewdly adapted their advertising tactics to circumvent the ban and maintain their access to this impressionable--and growing--market share.

How they do it is the subject of a recent study led by Dr. Yael Bar-Zeev at Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU)'s Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine at HU-Hadassah Medical Center. She also serves as Chair of the Israeli Association for Smoking Cessation and Prevention, and teamed up with colleagues at HU and George Washington University. They published their findings in Nicotine and Tobacco Research.

Their study ...

July 12, 2021 - Transitions between healthcare sites - such as from the hospital to home or to a skilled nursing facility - carry known risks to patient safety. Many programs have attempted to improve continuity of care during transitions, but it remains difficult to establish and compare the benefits of these complex interventions. An update on patient-centered approaches to transitional care research and implementation is presented in a supplement to the August issue of Medical Care, sponsored by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Medical Care is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters ...

North Carolina State University researchers have developed a new technique that can alter plant metabolism. Tested in tobacco plants, the technique showed that it could reduce harmful chemical compounds, including some that are carcinogenic. The findings could be used to improve the health benefits of crops.

"A number of techniques can be used to successfully reduce specific chemical compounds, or alkaloids, in plants such as tobacco, but research has shown that some of these techniques can increase other harmful chemical compounds while reducing the target compound," said De-Yu Xie, professor of plant and microbial biology at NC State and the corresponding author of a paper describing the research. "Our technology ...

Snowmelt - the surface runoff from melting snow - is an essential water resource for communities and ecosystems. But extreme snow melt, which occurs when snow melts too rapidly over a short amount of time, can be destructive and deadly, causing floods, landslides and dam failures.

To better understand the processes that drive such rapid melting, researchers set out to map extreme snowmelt events over the last 30 years. Their findings are published in a new paper in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

"When we talk about snowmelt, people want to know the basic numbers, just like the weather, but no one has ever provided anything like that before. It's like if nobody told you the maximum and minimum temperature or record temperature in your city," said study co-author ...

The transportation sector is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, and a lot of attention has been devoted to electric passenger vehicles and their potential to help reduce those emissions.

But with the rise of online shopping and just-in-time shipping, electric delivery fleets have emerged as another opportunity to reduce the transportation sector's environmental impact.

Though EVs represent a small fraction of delivery vehicles today, the number is growing. In 2019, Amazon announced plans to obtain 100,000 electric delivery vehicles. UPS has ordered 10,000 of them and FedEx plans to be fully electric by 2040.

Now, a study from University of Michigan ...

New Brunswick, NJ--Children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) who are treated initially with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) and glucocorticoids have reduced risk for serious short-term outcomes, including cardiovascular dysfunction, than those who receive an initial treatment of IVIG alone, a new study finds.

MIS-C is a rare but serious--and sometimes fatal--condition associated with COVID-19, in which different body organs or systems become inflamed, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal system. It can occur weeks after having COVID-19 and even if the child or caregivers did not know the child had been infected.

The new study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, analyzed treatment ...

Taken together, the bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microbes that live in our intestines form the gut microbiome, which plays a key role in the health of people and animals. In new research from the University of Minnesota, University of Notre Dame and Duke University, scientists found that genetics nearly always plays a role in the composition of the gut microbiome of wild baboons.

"In humans, research has shown that family members share a significant portion of microbes in their gut, but it's hard to answer if our microbiome is shaped more by nature, such as those ...