Modified yeast inhibits fungal growth in plants

External application could reduce agricultural reliance on fungicides

2021-07-15

(Press-News.org) About 70-80% of crop losses due to microbial diseases are caused by fungi. Fungicides are key weapons in agriculture's arsenal, but they pose environmental risks. Over time, fungi also develop a resistance to fungicides, leading growers on an endless quest for new and improved ways to combat fungal diseases.

The latest development takes advantage of a natural plant defense against fungus. In a paper published in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, engineers and plant pathologists at UC Riverside describe a way to engineer a protein that blocks fungi from breaking down cell walls, as well as a way to produce this protein in quantity for external application as a natural fungicide. The work could lead to a new way of controlling plant disease that reduces reliance on conventional fungicides.

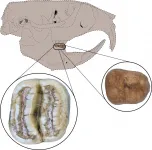

To gain entrance into plant tissues, fungi produce enzymes that use catalytic reactions to break down tough cell walls. Among these are polygalacturonases, or PGs, but plants are not helpless against this attack. Plants produce proteins called PG-inhibiting proteins, or PGIPs, that slow catalysis.

A group of UC Riverside researchers located the segment of DNA that tells the plant how to make PGIPs in common green beans. They inserted complete and partial segments into the genomes of baker's yeast to make the yeast produce PGIPs. The team used yeast instead of plants because yeast has no PGIPs of its own to muddy the experiment and grows quicker than plants.

After confirming the yeast was replicating with the new DNA, the researchers introduced it to cultures of Botrytis cinerea, a fungus that causes gray mold rot in peaches and other crops; and Aspergillus niger, which causes black mold on grapes and other fruits and vegetables.

Yeast that had both the complete and partial DNA segments that coded for PGIP production successfully retarded fungal growth. The result indicates the yeast was producing enough PGIPs to make the method a potential candidate for large-scale production.

"These results reaffirm the potential of using PGIPs as exogenous applied agents to inhibit fungal infection," said Yanran Li, a Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering, who worked on the project with plant pathologist Alexander Putman in the Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology. "PGIPs only inhibit the infection process but are likely not fatal to any fungi. Therefore, the application of this natural plant protein-derived peptide to crops will likely have minimal impact on plant-microbe ecology."

Li also said that PGIPs probably biodegrade into naturally occurring amino acids, meaning fewer potential effects for consumers and the environment when compared with synthetic small molecule fungicides.

"The generation of transgenic plants is time-consuming and the application of such transgenic crops in agricultural industry requires a long approval period. On the other hand, the engineered PGIPs that are derived from natural proteins are applicable as a fast-track product for FDA approval, if they can be utilized exogenously in a manner similar to a fungicide," Li said.

By tweaking the yeast a slightly different way, the researchers were able to make it exude PGIPs for external application. Previous studies have shown freeze drying naturally occurring microbes on apples, then reconstituting them in a solution and spraying them on crops, greatly reduces fungal disease and loss during shipping. The authors suggest that PGIP-expressing yeast could be used the same way. They caution, however, that because plants also form beneficial relationships with some fungi, future research needs to ensure plants only repel harmful fungi.

Li will continue to engineer PGIPs for enhanced efficiency and broader spectrum against various pathogenic fungi. Meanwhile, Li and Putman will keep evaluating the potential of using engineered PGIPs to suppress fungi-induced pre-harvest and post-harvest disease.

INFORMATION:

Li and Putman were joined in the research by doctoral student Tiffany Chiu and plant pathologist Anita Behari, both of whom are at UC Riverside, and Justin Chartron, who was a professor at UC Riverside when the research was conducted. The paper, "Exploring the potential of engineering polygalacturonase?inhibiting protein as an ecological, friendly, and nontoxic pest control agent," is available here. The work was supported by LG Chem Ltd. and the Frank G. and Janice B. Delfino Agricultural Technology Research Initiative and partially supported by the National Institutes of Health.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-15

What are the fundamental skills that young children need to develop at the start of school for future academic success? While a large body of research shows strong links between cognitive skills (attention, memory, etc.) and academic skills on the one hand, and emotional skills on the other, in students from primary school to university, few studies have explored these links in children aged 3 to 6 in a school context. Researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Valais University of Teacher Education, Switzerland (HEP-VS), in collaboration with teachers from Savoie in France and their pedagogical advisor, examined the links between emotion knowledge, cooperation, locomotor activity and numerical skills in 706 pupils aged 3 to 6. The results, to be read in the journal ...

2021-07-15

Contamination of urban lakes, rivers and surface water by human waste is creating pools of 'superbugs' in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) - but improving access to clean water, sanitation and sewerage infrastructure could help to protect people's health, a new study reveals.

Researchers studied bodies of water in urban and rural sites in three areas of Bangladesh - Mymensingh, Shariatpur and Dhaka. They found more antibiotic resistant faecal coliforms in urban surface water compared to rural settings, consistent with reports of such bacteria in rivers across Asia.

Publishing their findings in mSystems today, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh call for further research to quantify the drivers ...

2021-07-15

COVID-19 NEWS: CAN DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS HELP THE IMMUNE SYSTEM FIGHT CORONAVIRUS INFECTION?

Media Contact: Patrick Smith, pjsmith88@jhmi.edu

Johns Hopkins Medicine gastroenterologist Gerard Mullin, M.D., and a team of co-authors published an article May 11, 2021, in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology that details the scientific rationale and possible benefits -- as well as possible drawbacks -- of several dietary supplements currently in clinical trials related to COVID-19 treatment.

According to business analysts, the U.S. nutritional supplement industry grew as much as 14.5% in 2020, due in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mullin, associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University ...

2021-07-15

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Two fossil teeth from a distant relative of North American gophers have scientists rethinking how some mammals reached the Caribbean Islands.

The teeth, excavated in northwest Puerto Rico, belong to a previously unknown rodent genus and species, now named Caribeomys merzeraudi. About the size of a mouse, C. merzeraudi is the Caribbean's smallest known rodent and one of the region's oldest, dating back about 29 million years.

It also represents the first discovery of a Caribbean rodent from a North American lineage, a finding that complicates an idea ...

2021-07-15

A new study by the University of Malta and Staffordshire University highlights an urgent need for change in the curriculum and demonstrates how introducing longer, more frequent and more physically intense PE lessons can significantly improve children's weight and overall health.

Malta currently has one of the highest rates of obesity worldwide with 40% of primary and 42.6% of secondary school children being overweight or obese.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children engage in at least 60 minutes of age-appropriate moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily, however ...

2021-07-15

New Rochelle, NY, July 14, 2021-Firsthand reports from nurses in correctional facilities detail the challenges they faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. These firsthand accounts are reported in a special issue on correctional nursing in the Journal of Correctional Health Care. Click here (https://www.liebertpub.com/toc/jchc/27/2) to read the issue now.

Karen Monsen, PhD, RN, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, and colleagues present the Omaha System COVID-19 Response Guidelines, which provide evidence-based pandemic response interventions used in correctional ...

2021-07-15

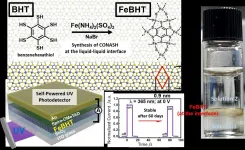

Converting light to electricity effectively has been one of the persistent goals of scientists in the field of optoelectronics. While improving the conversion efficiency is a challenge, several other requirements also need to be met. For instance, the material must conduct electricity well, have a short response time to changes in input (light intensity), and, most importantly, be stable under long-term exposure.

Lately, scientists have been fascinated with "coordination nanosheets" (CONASHs), that are organic-inorganic hybrid nanomaterials in which organic molecules are bonded to metal atoms in a 2D network. The interest in CONASHs stems mainly from their ability to absorb light at multiple wavelength ranges and convert ...

2021-07-15

Indiana Jones hates snakes. And he's certainly not alone. The fear of snakes is so common it even has its own name: ophidiophobia.

Kibret Mequanint doesn't particularly like the slithery reptiles either (he actually hates them too) but the Western University bioengineer and his international collaborators have found a novel use for snake venom: a body tissue 'super glue' that can stop life-threatening bleeding in seconds.

Over the past 20 years, Mequanint has developed a number of biomaterials-based medical devices and therapeutic technologies - some of which are either licensed to medical companies or are in the advanced stage of preclinical testing.

His latest collaborative research discovery ...

2021-07-15

Penn State College of Engineering researchers set out to develop technology capable of localizing and imaging blood clots in deep veins. Turns out their work may not only identify blood clots, but it may also be able to treat them.

The team, led by Scott Medina, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, published its results in Advance Healthcare Materials.

"Deep vein thrombosis is the formation of blood clots in deep veins, typically in a person's legs," said Medina. "It's a life-threatening blood clotting condition that, if left unaddressed, can cause deadly pulmonary embolisms -- when the clot travels to the lungs and blocks an artery. To manage DVT, and prevent these life-threating complications, it's critical to be able to rapidly detect, monitor and treat it."

The ...

2021-07-15

The research seeks to understand what drives decisions in data analyses and the process through which academics test a hypothesis by comparing the analyses of different researchers who tested the same hypotheses on the same dataset. Analysts reported radically different analyses and dispersed empirical outcomes, including, in some cases, significant effects in opposite directions from each other. Decisions about variable operationalizations explained the lack of consistency in results beyond statistical choices (i.e., which analysis or covariates to use).

"Our findings illustrate the importance of analytical choices and how different statistical methods can lead to different conclusions," says Martin Schweinsberg. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Modified yeast inhibits fungal growth in plants

External application could reduce agricultural reliance on fungicides