Brain 'noise' keeps nerve connections young

2021-07-20

(Press-News.org) Neurons communicate through rapid electrical signals that regulate the release of neurotransmitters, the brain's chemical messengers. Once transmitted across a neuron, electrical signals cause the juncture with another neuron, known as a synapse, to release droplets filled with neurotransmitters that pass the information on to the next neuron. This type of neuron-to-neuron communication is known as evoked neurotransmission.

However, some neurotransmitter-packed droplets are released at the synapse even in the absence of electrical impulses. These miniature release events -- or minis -- have long been regarded as 'background noise', says Brian McCabe, Director of the Laboratory of Neural Genetics and Disease and a Professor in the EPFL Brain Mind Institute.

But several studies have suggested that minis do have a function -- and an important one. In 2014, for example, McCabe and his team showed that minis are important for the development of synapses. If neurons in the brain were a network of computers, evoked releases would be packets of data through which the machines exchange information, whereas minis would be pings -- brief electronic signals that determine if there is a connection between two computers, McCabe says. "Minis are the pings that neurons use to say 'I am connected.'"

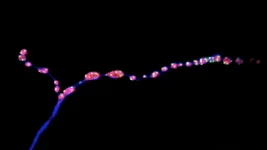

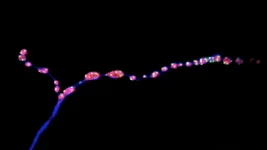

To assess whether minis could play a role in the mature nervous system, Soumya Banerjee, a postdoc in McCabe's group, and his colleagues set out to study a set of neurons that control movement in fruit flies. As the insects aged, their synapses started to break up into smaller fragments, the researchers found. (A similar process occurs in aging mammals, including people.) As nerve junctions broke down, both evoked and miniature neurotransmission were dampened, and the flies showed motor problems such as a reduced ability to climb the walls of a plastic vial.

Next, the team assessed the effects of stimulating or inhibiting evoked and miniature neurotransmission. When both types of neurotransmission were blocked, synapses aged prematurely, suggesting that during aging or in neurological diseases associated with old age, changes in neurotransmission happen before synapses start to crumble. This finding, McCabe says, upends a longstanding idea in neuroscience. "The idea has long been that the structure of the synapse breaks down, and that causes a functional change in the synapse, but we found it is the other way around," he says.

Stimulating evoked neurotransmission alone had no effect on aging synapses, the researchers found. However, increasing the frequency of minis kept synapses intact and preserved the motor ability of middle-aged flies at levels comparable to those of young flies. "Motor ability declines in all aging animals, including humans, so it was a delightful surprise to see that we could change that," McCabe says.

The findings, published in Nature Communications, could have important implications for human health: minis have been found at every type of synapse studied so far, and defects in miniature neurotransmission have been linked to range of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Figuring out how a reduction in miniature neurotransmission changes the structure of synapses, and how that in turn affects behavior, could help to better understand neurodegenerative disorders and other brain conditions.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-20

Every spring, the Daylight Saving Time shift robs people of an hour of sleep - and a new study shows that DNA plays a role in how much the "spring forward" time change affects individuals.

People whose genetic profile makes them more likely to be "early birds" the rest of the year can adjust to the time change in a few days, the study shows. But those who tend to be "night owls" could take more than a week to get back on track with sleep schedule, according to new data published in Scientific Reports by a team from the University of Michigan.

The study uses data from continuous sleep tracking ...

2021-07-20

Forensics specialists can use a commercial assay targeting mitochondrial DNA to accurately discriminate between wolf, coyote and dog species, according to a new study from North Carolina State University. The genetic information can be obtained from smaller or more degraded samples, and could aid authorities in prosecuting hunting jurisdiction violations and preserving protected species.

In the U.S., certain wolf subspecies or species are endangered and restricted in terms of hunting status. It is also illegal to deliberately breed wolves or coyotes with domesticated dogs.

"If ...

2021-07-20

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Diagnosing a rare medical condition is difficult. Identifying a treatment for it can take years of trial and error. In a serendipitous intersection of research expertise, an ill patient in this case a child and innovative technology, Bachmann-Bupp Syndrome has gone from a list of symptoms to a successful treatment in just 16 months.

The paper chronicling this lightning-fast scientific response to the Bachmann-Bupp Syndrome was published in the open-access journal, eLife.

For more than 25 years, André Bachmann, professor of pediatrics in Michigan State University College ...

2021-07-20

New research adds to a body of evidence indicating decisions about withdrawing life-sustaining treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) should not be made in the early days following injury.

In a July 6, 2021, study published in JAMA Neurology, researchers led by UC San Francisco, Medical College of Wisconsin and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital followed 484 patients with moderate-to-severe TBI. They found that among the patients in a vegetative state, 1 in 4 "regained orientation" - meaning they knew who they were, their ...

2021-07-20

By Luciana Constantino | Agência FAPESP – A pregnant woman infected by zika virus does not face a greater risk of giving birth to a baby with microcephaly if she has previously been exposed to dengue virus, according to a Brazilian study that compared data for pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro and Manaus.

A zika epidemic broke out in Brazil in 2015-16 in areas where dengue is endemic. Both viruses are transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Some of the states affected by the zika epidemic reported a rise in cases of microcephaly, a rare neurological disorder in which the baby’s brain fails to develop completely. Others saw no such rise.

According to this new study by Brazilian researchers, two factors explain the rise in microcephaly in only some areas: the ...

2021-07-20

When it comes to improving access to mental health services for children and families in low-income communities, a University of Houston researcher found having a warm handoff, which is a transfer of care between a primary care physician and mental health provider, will help build trust with the patient and lead to successful outcomes.

"Underserved populations face certain obstacles such as shortage of providers, family beliefs that cause stigma around mental health care, language barriers, lack of transportation and lack of insurance. A warm handoff, someone who serves as a go-between for experts and patients, can ensure connections are made," said Quenette L. Walton, assistant professor at the ...

2021-07-20

Irvine, CA - July 20, 2021 - In a new University of California, Irvine-led study, researchers found that a certain protein prevented regulatory T cells (Tregs) from effectively doing their job in controlling the damaging effects of inflammation in a model of multiple sclerosis (MS), a devastating autoimmune disease of the nervous system.

Published this month in Science Advances, the new study illuminates the important role of Piezo1, a specialized protein called an ion channel, in immunity and T cell function related to autoimmune neuroinflammatory disorders.

"We found that Piezo1 selectively restrains Treg cells, limiting their potential to mitigate ...

2021-07-20

Newborns at risk for Type 1 diabetes because they were given antibiotics may have their gut microorganisms restored with a maternal fecal transplant, according to a Rutgers study.

The study, which involved genetic analysis of mice, appears in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

The findings suggest that newborns at risk for Type 1 diabetes because their microbiome - the trillions of beneficial microorganisms in and on our bodies - were disturbed can have the condition reversed by transplanting fecal microbiota from their mother into their gastrointestinal tract after the antibiotic course has been completed.

Type 1 diabetes is the most ...

2021-07-20

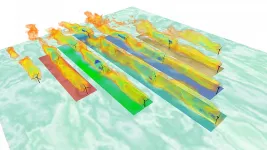

WASHINGTON, July 20, 2021 -- In the wind power industry, optimization of yaw, the alignment of a wind turbine's angle relative to the horizonal plane, has long shown promise for mitigating wake effects that cause a downstream turbine to produce less power than its upstream partner. However, a critical missing puzzle piece in the application of this knowledge has recently been added -- how to automate the identification of which turbines are experiencing wake effects amid changing wind conditions.

In the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, ...

2021-07-20

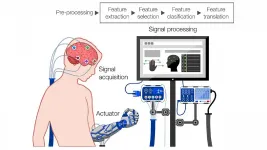

WASHINGTON, July 20, 2021 -- Surpassing the biological limitations of the brain and using one's mind to interact with and control external electronic devices may sound like the distant cyborg future, but it could come sooner than we think.

Researchers from Imperial College London conducted a review of modern commercial brain-computer interface (BCI) devices, and they discuss the primary technological limitations and humanitarian concerns of these devices in APL Bioengineering, from AIP Publishing.

The most promising method to achieve real-world BCI applications is through electroencephalography (EEG), a method ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Brain 'noise' keeps nerve connections young