(Press-News.org) Every spring, the Daylight Saving Time shift robs people of an hour of sleep - and a new study shows that DNA plays a role in how much the "spring forward" time change affects individuals.

People whose genetic profile makes them more likely to be "early birds" the rest of the year can adjust to the time change in a few days, the study shows. But those who tend to be "night owls" could take more than a week to get back on track with sleep schedule, according to new data published in Scientific Reports by a team from the University of Michigan.

The study uses data from continuous sleep tracking of 831 doctors in the first year of post-medical school training when the time shift occurred in spring 2019. All were first-year residents or "interns" in medical parlance, and taking part in the Intern Health Study based at the Michigan Neuroscience Institute.

From the large UK Biobank dataset, the researchers calculated genomic "chronotype" predisposition information, also known as the Objective Sleep Midpoint polygenic score. People with low scores were genomically predisposed to be "early birds" and those with high scores were genomically "night owls."

The team then applied these genomic scores in the intern sample and focused on the two groups of about 130 physicians each that had the strongest tendencies to be "early birds" and "night owls" based on their scores. The researchers looked at how their sleep patterns changed from the week before DST to the weekend after it.

In general, the difference in post-DST weekday wakeup times between the two groups was not large - probably because first-year medical residents have very strict work schedules.

In fact, the stressful duties and demanding schedules that interns endure is what made this population such an interesting one to study, and the larger Intern Health Study that the data come from has yielded important findings about the relationship between stress, sleep, genetics, mood and mental health.

But the time they got to sleep on the nights before workdays, and both sleep and wake times on the weekend, varied significantly between the two groups. The DST change made the differences even more pronounced.

Early birds had adjusted their sleep times by Tuesday, but night owls were still off track on the following Saturday.

Margit Burmeister, Ph.D., the U-M neuroscientist and geneticist who is the paper's senior and corresponding author, says the study gives one more strong reason for abolishing Daylight Saving Time.

"It's already known that DST has effects on rates of heart attacks, motor vehicle accidents, and other incidents, but what we know about these impacts mostly comes from looking for associations in large data pools after the fact," she says. "These data from direct monitoring and genetic testing allows us to directly see the effect, and to see the differences between people with different circadian rhythm tendencies that are influenced by both genes and environment. To put it plainly, DST makes everything worse for no good reason."

The study's first author is Jonathan Tyler, Ph.D., a postdoctoral assistant professor of mathematics at U-M.

Sleep schedules depend on a combination of many factors - but the fact that people can react so differently to the same abrupt change in time makes it important to study further.

The researchers also looked at the "fall back" time change in autumn and found no significant differences between early birds and night owls in how they reacted to the abrupt addition of an hour of sleep.

The findings have implications not just for the annual spring time change, but also for shift workers, travelers across time zones and even people deciding which profession to choose, the researchers note. Burmeister says she hopes to look further at differences between people in different professions in future studies.

Co-author Srijan Sen, M.D., Ph.D. who leads the Intern Health Study and directs the Frances and Kenneth Eisenberg and Family Depression Center at U-M, continues to lead other studies of how each year's crop of interns at over 100 hospitals react to the stresses of their training. The interns in the newly published study, like all interns, are in general chronically sleep-deprived because of the number of hours they need to be on duty or preparing for duty.

"This study is a demonstration of how we much we vary in our response to even relatively minor challenges to our daily routines, like DST," he said. "Discovering the mechanisms underlying this variation can help us understand our individual strengths and vulnerabilities better."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Burmeister, Tyler and Sen, the study's authors are Yu Fang, M.S.E., Cathy Goldstein, M.D., M.S. and Daniel Forger, Ph.D. Burmeister, Sen, and Goldstein are faculty at the U-M Medical School, where Fang is a research specialist. Forger is a professor of mathematics in the U-M College of Literature, Science and the Arts, and of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the Medical School.

Funding for the study and the Intern Health Study came from the National Institutes of Health (HL007622, MH101459).

Forensics specialists can use a commercial assay targeting mitochondrial DNA to accurately discriminate between wolf, coyote and dog species, according to a new study from North Carolina State University. The genetic information can be obtained from smaller or more degraded samples, and could aid authorities in prosecuting hunting jurisdiction violations and preserving protected species.

In the U.S., certain wolf subspecies or species are endangered and restricted in terms of hunting status. It is also illegal to deliberately breed wolves or coyotes with domesticated dogs.

"If ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Diagnosing a rare medical condition is difficult. Identifying a treatment for it can take years of trial and error. In a serendipitous intersection of research expertise, an ill patient in this case a child and innovative technology, Bachmann-Bupp Syndrome has gone from a list of symptoms to a successful treatment in just 16 months.

The paper chronicling this lightning-fast scientific response to the Bachmann-Bupp Syndrome was published in the open-access journal, eLife.

For more than 25 years, André Bachmann, professor of pediatrics in Michigan State University College ...

New research adds to a body of evidence indicating decisions about withdrawing life-sustaining treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) should not be made in the early days following injury.

In a July 6, 2021, study published in JAMA Neurology, researchers led by UC San Francisco, Medical College of Wisconsin and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital followed 484 patients with moderate-to-severe TBI. They found that among the patients in a vegetative state, 1 in 4 "regained orientation" - meaning they knew who they were, their ...

By Luciana Constantino | Agência FAPESP – A pregnant woman infected by zika virus does not face a greater risk of giving birth to a baby with microcephaly if she has previously been exposed to dengue virus, according to a Brazilian study that compared data for pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro and Manaus.

A zika epidemic broke out in Brazil in 2015-16 in areas where dengue is endemic. Both viruses are transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Some of the states affected by the zika epidemic reported a rise in cases of microcephaly, a rare neurological disorder in which the baby’s brain fails to develop completely. Others saw no such rise.

According to this new study by Brazilian researchers, two factors explain the rise in microcephaly in only some areas: the ...

When it comes to improving access to mental health services for children and families in low-income communities, a University of Houston researcher found having a warm handoff, which is a transfer of care between a primary care physician and mental health provider, will help build trust with the patient and lead to successful outcomes.

"Underserved populations face certain obstacles such as shortage of providers, family beliefs that cause stigma around mental health care, language barriers, lack of transportation and lack of insurance. A warm handoff, someone who serves as a go-between for experts and patients, can ensure connections are made," said Quenette L. Walton, assistant professor at the ...

Irvine, CA - July 20, 2021 - In a new University of California, Irvine-led study, researchers found that a certain protein prevented regulatory T cells (Tregs) from effectively doing their job in controlling the damaging effects of inflammation in a model of multiple sclerosis (MS), a devastating autoimmune disease of the nervous system.

Published this month in Science Advances, the new study illuminates the important role of Piezo1, a specialized protein called an ion channel, in immunity and T cell function related to autoimmune neuroinflammatory disorders.

"We found that Piezo1 selectively restrains Treg cells, limiting their potential to mitigate ...

Newborns at risk for Type 1 diabetes because they were given antibiotics may have their gut microorganisms restored with a maternal fecal transplant, according to a Rutgers study.

The study, which involved genetic analysis of mice, appears in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

The findings suggest that newborns at risk for Type 1 diabetes because their microbiome - the trillions of beneficial microorganisms in and on our bodies - were disturbed can have the condition reversed by transplanting fecal microbiota from their mother into their gastrointestinal tract after the antibiotic course has been completed.

Type 1 diabetes is the most ...

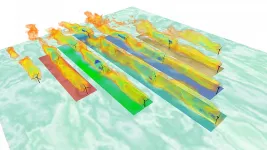

WASHINGTON, July 20, 2021 -- In the wind power industry, optimization of yaw, the alignment of a wind turbine's angle relative to the horizonal plane, has long shown promise for mitigating wake effects that cause a downstream turbine to produce less power than its upstream partner. However, a critical missing puzzle piece in the application of this knowledge has recently been added -- how to automate the identification of which turbines are experiencing wake effects amid changing wind conditions.

In the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, ...

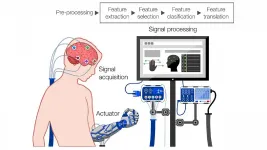

WASHINGTON, July 20, 2021 -- Surpassing the biological limitations of the brain and using one's mind to interact with and control external electronic devices may sound like the distant cyborg future, but it could come sooner than we think.

Researchers from Imperial College London conducted a review of modern commercial brain-computer interface (BCI) devices, and they discuss the primary technological limitations and humanitarian concerns of these devices in APL Bioengineering, from AIP Publishing.

The most promising method to achieve real-world BCI applications is through electroencephalography (EEG), a method ...

Millions of people in countries around the world could face an increased risk of malnutrition as climate change threatens their local fisheries.

New projections examining more than 800 fish species in more than 157 countries have revealed how two major, and growing, pressures - climate change and over-fishing - could impact the availability of vital micronutrients from our oceans.

As well as omega-3 fatty acids, fish are an important source of iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamin A. A lack of these vital micronutrients is linked to conditions such as maternal mortality, stunted growth, and pre-eclampsia.

Analyses by an international team from the UK and Canada and led by scientists from Lancaster ...