(Press-News.org) LAWRENCE -- A new paper appearing the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences gives new detail and understanding to the cultivation of corn, one of the United States' biggest cash crops.

The research by a team at the University of Kansas centers on "hybrid vigor," also known as "heterosis," a well-known phenomenon where crosses between inbred lines of corn and other crops produce offspring that outperform their parents in yield, drought resistance and other desirable qualities. Yet, the mechanisms underpinning heterosis are little understood despite over a century of intensive research.

The new PNAS research examines the relationship between heterosis and soil microbes, showing, in most cases, heterosis is facilitated by a microbial community.

"Hybrid vigor is super important in agriculture because one of the reasons for the great increases in crop productivity over the last several decades has been the use of hybrid cultivars, which tend to be much more productive and stronger and healthier than inbred cultivars," said lead author Maggie Wagner, assistant scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research and assistant professor with the KU Department of Ecology & Evolutionary biology. "Despite how important this is we still don't fully understand why hybrids are so superior to inbreds. A lot of focus has been on the genetics of hybrid vigor, which makes sense because hybridization is a genetic process -- but there's been some evidence the environment is important as well for affecting the strength of hybrid vigor. In this paper, we showed microbes living in the soil are one of the environmental factors that have a really important effect on hybrid vigor."

In a series of experiments, Wagner and her co-authors found in most cases inbred parent lines and hybrid crosses perform similarly under sterile conditions, without the presence of microbes -- but heterosis "can be restored by inoculation with a simple community of seven bacterial strains." The researchers saw the same results for seedlings inoculated with "autoclaved versus live soil slurries in a growth chamber and for plants grown in steamed or fumigated versus untreated soil in the field."

Wagner's co-authors at KU were Kayla Clouse and Laura Phillips. Other co-authors were Clara Tang, Fernanda Salvato, Alexandria Bartlett, Simina Vintila, Manuel Kleiner, Mark Hoffmann, Shannon Sermons and Peter Balint-Kurti at North Carolina State University. Sermons and Balint-Kurti also work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

"In lab experiments, we essentially grew the plants inside plastic bags in order to provide a completely sterile environment for them," Wagner said. "That allowed us to completely control which microbes, if any, were interacting with the plants. So, it's just some basic microbiology, along with a new kind of growth environment. But then in the field, we tried several different approaches to sterilize the soil, including just steam fumigation, which is used often, especially in fruit and vegetable production. It's not really generally used for corn growth, but for this experiment it made sense for us to do that. And we tried some chemical fumigants as well, and got similar results with all those methods."

In the soil-steaming experiment at the KU Field Station -- which temporarily eliminates or reduces microbes -- the researchers found the steaming "increased rather than decreased heterosis, indicating that the direction of the effect depends on community composition, environment or both."

"It's complicated, and we don't fully understand what's going on yet," Wagner said. "The first three experiments all showed the exact same direction of the effect. But then for the fourth experiment, we again found that microbes influenced heterosis but it was in the opposite direction, where the hybrid had a more positive reaction to sterile conditions. We think that this could just be due to some something particular to the microbial community in the soil for this one experiment, but we're not sure yet."

The new paper is to be followed by research in the same vein supported by a $900,000 new grant from the National Science Foundation involving many of the same personnel, with Wagner acting as one of the principal investigators.

The grant work will follow three lines of investigation: testing a range of microbes for their ability to boost hybrid vigor in corn; finding genetic variants and regions of the corn genome that respond to soil microbes; and researching how microbes behave within the roots of inbred and hybrid corn at the molecular level. The investigators hope their work could lead to better techniques in agriculture and conservation.

"We have this very basic observation of microbes affecting hybrid vigor, but we weren't able to follow up on it without some funding -- this grant is going to push the same line of research forward," Wagner said. "My collaborators are Manuel Kleiner at N.C. State who is an expert in metaproteomics, which is a way to measure the protein expression of microbes inside plant roots. We're hoping to learn more about how hybrids and inbreds are interacting with microbes differently, possibly by influencing the microbes' behavior. Our other collaborator is Peter Balint-Kurti with the USDA. He's an expert in the maize immune system and the genetic basis of disease resistance, so he's going to map some genes related to hybrids' responses to microbes. Here at Kansas, a graduate student in my lab, Kayla Clouse, will look at some of the broader patterns of this phenomenon -- for example, we don't know yet if all maize hybrids will react to microbes in the same way. So far, we've only confirmed this in one hybrid, so we need to figure out how generalizable it is -- and we're also hoping to figure out what is it about the microbial community that that can affect this response in either direction. A lot of her future dissertation work will be related to this project."

Work under the NSF grant will continue through 2024.

INFORMATION:

Ten years after one of the largest nuclear accidents in history spewed radioactive contamination over the landscape in Fukushima, Japan, a University of Georgia study has shown that radioactive contamination in the Fukushima Exclusion Zone can be measured through its resident snakes.

The team's findings, published in the recent journal of Ichthyology & Herpetology, report that rat snakes are an effective bioindicator of residual radioactivity. Like canaries in a coal mine, bioindicators are organisms that can signal an ecosystem's health.

An abundant species in Japan, rat snakes travel short distances and can accumulate high levels of radionuclides. According ...

A recent study led by Geoff Burns, an elite runner and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan Exercise & Sport Science Initiative, compared the "bouncing behavior"--the underlying spring-like physics of running--in elite-level male runners (sub-four-minute milers) vs. highly trained but not elite runners.

Subjects ran on a treadmill instrumented with a pressure plate beneath the belt, so Burns and colleagues could see how much time they spent in the air and in contact with the ground. When running, muscles and limbs coordinate to act like a giant pogo stick, and those muscles, tendons and ligaments interact to recycle energy from step to step, Burns says.

The researchers looked at the basic physics of the runners ...

Routine adolescent preventive visits provide important opportunities for promoting sexual and reproductive health and for preventing unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

A new study END ...

We all like to think that we know ourselves best, but, given that our brain activity is largely governed by our subconscious mind, it is probably our brain that knows us better! While this is only a hypothesis, researchers from Japan have already proposed a content recommendation system that assumes this to be true. Essentially, such a system makes use of its user's brain signals (acquired using, say, an MRI scan) when exposed to a particular content and eventually, by exploring various users and contents, builds up a general model of brain activity.

"Once we obtain the 'ultimate' brain model, we should be able to perfectly estimate the brain activity of ...

July 19, 2021 - At the organization responsible for certifying the training and skills of US urologists, achieving and maintaining diversity, equity and inclusion is more than just a "numbers game," according to a special article in Urology Practice®, an Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

In the new article, the American Board of Urology (ABU) points out that the practice of diversity and inclusion has been a cornerstone of its values for years. However, the Board acknowledges that while progress has been made, ...

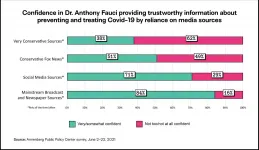

With more than two-thirds of American adults vaccinated with at least one dose of an authorized Covid-19 vaccine, the top U.S. health agencies retain the trust of the vast majority of the American public, as does Dr. Anthony Fauci, the public face of U.S. efforts to combat the virus, according to a new survey from the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania.

The survey revealed growing public confidence in both the safety and effectiveness of vaccines to prevent Covid-19.

But after months of attacks on Fauci in conservative and social media, the survey found that people who said they rely on conservative and very conservative media rather than other sources ...

Led by Dr Jonas Warneke, researchers at the Wilhelm Ostwald Institute of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry at Leipzig University have made a decisive advance in the study of one type of highly reactive particles. Based on their research, they now understand the "binding preferences" of these particles.

Their research serves as the basis for the targeted use of these highly reactive molecules, for example, to generate new molecular structures or to bind hazardous chemical "waste" and in this way dispose of it. The researchers have now published their findings in the journal Chemistry - A European Journal, and their research was featured on the cover thanks to the excellent review they received.

What molecules and people have in common

Molecules and people actually have a lot in ...

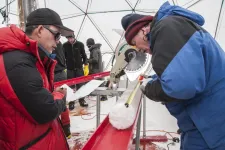

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists who study glacier ice have found viruses nearly 15,000 years old in two ice samples taken from the Tibetan Plateau in China. Most of those viruses, which survived because they had remained frozen, are unlike any viruses that have been cataloged to date.

The findings, published today in the journal Microbiome, could help scientists understand how viruses have evolved over centuries. For this study, the scientists also created a new, ultra-clean method of analyzing microbes and viruses in ice without contaminating it.

"These glaciers were formed gradually, and along with dust and ...

In order to correctly separate vehicles into classes, for instance for mobility pricing, one must be able to clearly distinguish mid-sized cars from upper class cars or small cars from compact cars. But this is becoming increasingly difficult: On photos, an Audi A4 looks almost the same as an Audi A6, a Mini One looks similar to a Mini Countryman. To date, there is no independent procedure for doing this.

Thus far, the classes in each country have been determined by experts - to a large extend at their own discretion. Empa researcher Naghmeh Niroomand has now developed a system that can classify cars worldwide based on their dimensions. Purely mathematical and fair. Thanks to it, the current classification ...

FORT LAUDERDALE/DAVIE, Fla. - It's good to have friends.

Most humans have experienced social anxiety on some level during their lives. We all know the feeling - we show up to a party thinking it is going to be chock full of friends, only to find nearly all total strangers. While we typically attribute the long-lasting bonds of social familiarity to complex thinkers like humans, growing evidence indicates that we underestimate the importance of friendship networks in seemingly "simple" animals, like fish, and its importance for survival in the wild. To better understand how familiarity impacts social fishes, a group of research scientists studied this idea using schooling coral reef fish.

"We studied how the presence of ...