(Press-News.org) Breaking a longstanding impasse in our understanding of olfaction, scientists at UC San Francisco (UCSF) have created the first molecular-level, 3D picture of how an odor molecule activates a human odorant receptor, a crucial step in deciphering the sense of smell.

The findings, appearing online March 15, 2023, in Nature, are poised to reignite interest in the science of smell with implications for fragrances, food science, and beyond. Odorant receptors - proteins that bind odor molecules on the surface of olfactory cells - make up half of the largest, most diverse family of receptors in our bodies; A deeper understanding of them paves the way for new insights about a range of biological processes.

"This has been a huge goal in the field for some time,” said Aashish Manglik, MD, PhD, an associate professor of pharmaceutical chemistry and a senior author of the study. The dream, he said, is to map the interactions of thousands of scent molecules with hundreds of odorant receptors, so that a chemist could design a molecule and predict what it would smell like.

“But we haven’t been able to make this map because, without a picture, we don’t know how odor molecules react with their corresponding odor receptors,” Manglik said.

A Picture Paints the Scent of Cheese

Smell involves about 400 unique receptors. Each of the hundreds of thousands of scents we can detect is made of a mixture of different odor molecules. Each type of molecule may be detected by an array of receptors, creating a puzzle for the brain to solve each time the nose catches a whiff of something new.

“It’s like hitting keys on a piano to produce a chord,” said Hiroaki Matsunami, PhD, professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University and a close collaborator of Manglik. Matsunami’s work over the past two decades has focused on decoding the sense of smell. “Seeing how an odorant receptor binds an odorant explains how this works at a fundamental level.”

To create that picture, Manglik’s lab used a type of imaging called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), that allows researchers to see atomic structure and study the molecular shapes of proteins. But before Manglik’s team could visualize the odorant receptor binding a scent molecule, they first needed to purify a sufficient quantity of the receptor protein.

Odorant receptors are notoriously challenging, some say impossible, to make in the lab for such purposes.

The Manglik and Matsunami teams looked for an odorant receptor that was abundant in both the body and the nose, thinking it might be easier to make artificially, and one that also could detect water-soluble odorants. They settled on a receptor called OR51E2, which is known to respond to propionate – a molecule that contributes to the pungent smell of Swiss cheese.

But even OR51E2 proved hard to make in the lab. Typical cryo-EM experiments require a milligram of protein to produce atomic-level images, but co-first author Christian Billesbøelle, PhD, a senior scientist in the Manglik Lab, developed approaches to use only 1/100th of a milligram of OR51E2, putting the snapshot of receptor and odorant within reach.

"We made this happen by overcoming several technical impasses that have stifled the field for a long time,” said Billesbøelle. “Doing that allowed us to catch the first glimpse of an odorant connecting with a human odorant receptor at the very moment a scent is detected.”

This molecular snapshot showed that propionate sticks tightly to OR51E2 thanks to a very specific fit between odorant and receptor. The finding jibes with one of the duties of the olfactory system as a sentinel for danger.

While propionate contributes to the rich, nutty aroma of Swiss cheese, on its own, its scent is much less appetizing.

“This receptor is laser focused on trying to sense propionate and may have evolved to help detect when food has gone bad,” said Manglik. Receptors for pleasing smells like menthol or caraway might instead interact more loosely with odorants, he speculated.

Just a Whiff

Along with employing a large number of receptors at a time, another interesting quality of the sense of smell is our ability to detect tiny amounts of odors that can come and go. To investigate how propionate activates this receptor, the collaboration enlisted quantitative biologist Nagarajan Vaidehi, PhD, at City of Hope, who used physics-based methods to simulate and make movies of how OR51E2 is turned on by propionate.

“We performed computer simulations to understand how propionate causes a shape change in the receptor at an atomic level,” said Vaidehi. “These shape changes play a critical role in how the odorant receptor initiates the cell signaling process leading to our sense of smell.”

The team is now developing more efficient techniques to study other odorant-receptor pairs, and to understand the non-olfactory biology associated with the receptors, which have been implicated in prostate cancer and serotonin release in the gut.

Manglik envisions a future where novel smells can be designed based on an understanding of how a chemical’s shape leads to a perceptual experience, not unlike how pharmaceutical chemists today design drugs based on the atomic shapes of disease-causing proteins.

“We’ve dreamed of tackling this problem for years,” he said. “We now have our first toehold, the first glimpse of how the molecules of smell bind to our odorant receptors. For us, this is just the beginning.”

Authors: Additional UCSF authors include Claudia Llinas del Torrent, Linus Li, and Bryan Faust, of the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry. For other authors, please see the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01DC020353, K99DC018333 and the UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, funded in part by the Sandler Foundation. Cryo-EM equipment at UCSF is partially supported by NIH grants S10OD020054 and S10OD021741. For other funding, please see the paper.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at https://ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

Making sense of scents: Deciphering our sense of smell

First molecular images of olfaction open door to creating novel smells

2023-03-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover key information about the function of mitochondria in cancer cells

2023-03-15

Scientists have long known that mitochondria, the "powerhouses" of cells, play a crucial role in the metabolism and energy production of cancer cells. However, until now, little was known about the relationship between the structural organization of mitochondrial networks and their functional bioenergetic activity at the level of whole tumors.

In a new study, published in Nature, researchers from the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center used positron emission tomography (PET) in combination ...

Artificial Sweetener could dampen immune response to disease in mice

2023-03-15

Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00hrs GMT Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Peer reviewed

Experimental study

Animals / Cells

Artificial Sweetener could dampen immune response to disease in mice

Scientists at the Francis Crick Institute have found that high consumption of a common artificial sweetener, sucralose, lowers activation of T-cells, an important component of the immune system, in mice.

If found to have similar effects in humans, one day it could be used therapeutically to help dampen T-cell responses. For example, in patients with autoimmune diseases who ...

New research shows recovering tropical forests offset just one quarter of carbon emissions from new tropical deforestation and forest degradation

2023-03-15

A pioneering global study has found deforestation and forests lost or damaged due to human and environmental change, such as fire and logging, are fast outstripping current rates of forest regrowth.

Tropical forests are vital ecosystems in the fight against both climate and ecological emergencies. The research, published today in Nature and led by the University of Bristol, highlights the carbon storage potential and the current limits of forest regrowth to addressing such crises.

The findings showed degraded forests recovering from human disturbances, and secondary forests regrowing ...

Targeting menin induces responses in acute leukemias with KMT2A rearrangements or NPM1 mutations

2023-03-15

Researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that inhibiting menin with revumenib, previously known as SNDX-5613, yielded encouraging responses for advanced acute leukemias with KMT2A rearrangements or mutant NPM1. Findings from the Phase I AUGMENT-101 trial were published today in Nature.

The overall response rate among 60 patients was 53%, and the rate of complete remission or complete remission with partial hematologic recovery was 30%, with 78% of patients achieving clearance of measurable residual disease. Responses were seen across multiple dose ...

Bird flu associated with hundreds of seal deaths in New England in 2022, Tufts researchers find

2023-03-15

Researchers at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University found that an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was associated with the deaths of more than 330 New England harbor and gray seals along the North Atlantic coast in June and July 2022, and the outbreak was connected to a wave of avian influenza in birds in the region.

The study was published on March 15 in the journal Emerging Infectious Disease.

HPAI is more commonly known as bird flu, and the H5N1 strain has been responsible for about 60 million poultry ...

Designing more useful bacteria

2023-03-15

In a step forward for genetic engineering and synthetic biology, researchers have modified a strain of Escherichia coli bacteria to be immune to natural viral infections while also minimizing the potential for the bacteria or their modified genes to escape into the wild.

The work promises to reduce the threats of viral contamination when harnessing bacteria to produce medicines such as insulin as well as other useful substances, such as biofuels. Currently, viruses that infect vats of bacteria can halt production, compromise ...

New laser technology developed by EPFL and IBM

2023-03-15

Scientists at EPFL and IBM have developed a new type of laser that could have a significant impact on optical ranging technology. The laser is based on a material called lithium niobate, often used in the field of optical modulators, which controls the frequency or intensity of light that is transmitted through a device.

Lithium niobate is particularly useful because it can handle a lot of optical power and has a high “Pockels coefficient”, which means that it can change its optical properties when an electric field is applied to it.

The researchers achieved their breakthrough by combining ...

How genome doubling helps cancer develop

2023-03-15

A single cell contains 2-3 meters of DNA, meaning that the only way to store it is to package it into tight coils. The solution is chromatin: a complex of DNA wrapped around proteins called histones. In the 3D space, this complex is progressively folded into a multi-layered organization composed of loops, domains, and compartments, which makes up what we know as chromosomes. The organization of chromatin is closely linked to gene expression and the cell’s proper function, so any problems in chromatin structure can have detrimental effects, including the development of cancer.

A common event in around 30% of all human cancers is “whole genome doubling” ...

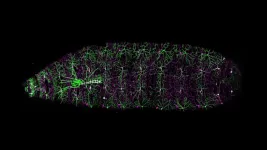

Magnificent wiring

2023-03-15

NEW YORK – For a functioning brain to develop from its embryonic beginnings, so much has to happen and go exactly right with exquisite precision, according to a just-so sequence in space and time. It’s like starting with a brick that somehow replicates and differentiates into a hundred types of building materials that also replicate, while simultaneously self-assembling into a handsome skyscraper replete with functioning thermal, plumbing, security and electrical systems.

The accompanying microscope image, from ...

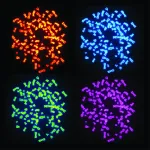

Self-driven laboratory, AlphaFlow, speeds chemical discovery

2023-03-15

A team of chemical engineering researchers has developed a self-driven lab that is capable of identifying and optimizing new complex multistep reaction routes for the synthesis of advanced functional materials and molecules. In a proof-of-concept demonstration, the system found a more efficient way to produce high-quality semiconductor nanocrystals that are used in optical and photonic devices.

“Progress in materials and molecular discovery is slow, because conventional techniques for discovering new chemistries rely on varying ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Industrial research labs were invented in Europe but made the U.S. a tech superpower

Enzymes work as Maxwell's demon by using memory stored as motion

Methane’s missing emissions: The underestimated impact of small sources

Beating cancer by eating cancer

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

A depression treatment that once took eight weeks may work just as well in one

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

[Press-News.org] Making sense of scents: Deciphering our sense of smellFirst molecular images of olfaction open door to creating novel smells