(Press-News.org) The Tibetan Plateau, the highest and largest plateau above sea level, is one of the harshest environments settled by humans. It has a cold and arid environment and its elevation often surpasses 4000 meters above sea level (masl). The plateau covers a wide expanse of Asia—approximately 2.5 million square kilometers—and is home to over 7 million people, primarily belonging to the Tibetan and Sherpa ethnic groups.

However, our understanding of their origins and history on the plateau is patchy. Despite a rich archaeological context spanning the plateau, sampling of DNA from ancient humans has been limited to a thin slice of the southwestern plateau in the Himalayas.

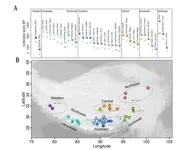

Now, a study published in Science Advances on March 17 led by Prof. FU Qiaomei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has filled this gap by sequencing the genomes of 89 ancient humans dating back to 5100 BP from 29 archaeological sites spanning the Tibetan Plateau.

The researchers found that ancient humans living across the plateau share a single origin, deriving from a northern East Asian population that admixed with a deeply diverged, yet unsampled, human population.

"This pattern is found in populations since 5100 years ago, prior to the arrival of domesticated crops on the plateau," said Prof. FU. She noted that the introduction of northern East Asian ancestry to plateau populations occurred before barley and wheat was introduced and was not associated with migrating wheat/barley agriculturalists.

A deeper comparison across the plateau reveals distinct genetic patterns prior to 2500 BP, indicating that three very different Tibetan populations occupied the northeastern, southern/central, and southern/southwestern regions of the plateau, with previously sampled plateau populations belonging only to the latter group.

Different population dynamics can be observed in these three regions. Northeastern populations younger than 4700 BP show an influx of additional northern East Asian ancestry in lower elevation regions (~3000 masl) such as the Gonghe Basin. However, this influx is not observed in higher elevation populations (~4000 masl) dating to 2800 BP just 500 km away.

An extended network of humans also lived along the Yarlung Tsangpo River, with a shared ancestry found in southern/southwestern populations dating to 3400 BP, western populations from Ngari Prefecture dating to 2300 BP, and southeastern populations from Nyingchi Prefecture dating to 2000 BP. The extended impact of these populations shows the important role this river valley played in Tibetan history.

"Between these two groups, central populations prior to 2500 BP share ancestry that differed from those further north and south. However, sampling of central populations after 1600 BP show that they share a closer genetic relationship to southern/southwestern populations. These patterns capture a dynamism in human populations on the plateau," said Melinda Yang, assistant professor at the University of Richmond and a previous postdoc at IVPP.

"While ancient plateau populations show primarily East Asian ancestry, Central Asian influences can be found in some ancient plateau populations," said WANG Hongru, professor at the Agricultural Genomics Institute in Shenzhen and a previous postdoc at IVPP. "Western populations show partial Central Asian ancestry as early as 2300 BP, and an individual dating to 1500 BP from the southwestern plateau additionally shows ancestry associated with Central Asian populations."

Present-day Tibetans and Sherpas show heavy influence from lowland East Asian populations, with differing levels of gene flow correlating with longitude. This pattern is not observed across populations of older time transects, including those dating from 1200–800 BP, indicating that lowland East Asian gene flow was largely a product of very recent human migration.

Previous research has shown that present-day plateau populations possess high frequencies of an endothelial Pas domain protein 1 (EPAS1) variant that is adaptive for living at high altitudes and likely originated from a past admixture event with the archaic humans known as Denisovans. "Humans from this study show archaic ancestry typical of lowland East Asians, but the oldest individual dating to 5100 BP is homozygous for the adaptive variant," said Prof. FU. "Thus, the arrival of this variant occurred prior to 5100 BP in the ancestral population that contributed to all plateau populations."

Through their broad spatiotemporal survey of ancient human DNA from the Tibetan Plateau, Prof. FU and her team have revealed a Tibetan lineage that dates back to at least 5100 years ago on the Tibetan Plateau. The ancestral population diversified rapidly, such that three regional groups show unique historical patterns that began to merge after 2500 BP.

"This is the largest study of ancient genetics on the Tibetan Plateau to date," said LU Hongliang, a professor at Sichuan University. The new evidence in this study on the formation of unique components in the ancient populations from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is highly reliant on collaboration between multiple archaeological teams and geneticists. Prof. LU notes that "Analyzing ancient DNA allows us to go beyond the study of cultural interaction using only archaeological evidence, and to put forward new ideas for archaeological research on the plateau."

Future sampling is still needed, as the origin of the unsampled, deeply diverged ancestry found in all plateau populations is still unaccounted for. In addition, when and where the adaptive EPAS1 allele first entered the ancestral Tibetan population is still unknown.

But this study is a step in the right direction. "These genomes reveal a deep and diversified history of humans on the plateau," said Prof. FU. "With these findings, we have a much better understanding of an important part of human history in Asia."

END

Genomic study of ancient humans sheds light on human evolution on the Tibetan Plateau

2023-03-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Key role identified for nervous system in severe allergic shock

2023-03-17

DURHAM, N.C. – A key feature of the severe allergic reaction known as anaphylaxis is an abrupt drop in blood pressure and body temperature, causing people to faint and, if untreated, potentially die.

That response has long been attributed to a sudden dilation and leakage of blood vessels. But in a study using mice, Duke Health researchers have found that this response, especially body temperature drop, requires an additional mechanism – the nervous system.

Appearing online March 17 in the journal Science Immunology, the study could ...

Researchers develop biodegradable, biorecyclable glass

2023-03-17

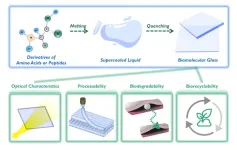

Everyone is familiar with glass—from putting on eyeglasses, pushing open the window, standing in front of a mirror, to holding a water glass. Glass is ubiquitous in nature and essential to human life.

But the widespread use of persistent, non-biodegradable glass that cannot be naturally eliminated causes long-term environmental hazards and social burdens.

To solve this problem, a research group led by Prof. YAN Xuehai from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has developed a family of eco-friendly glass of biological origin fabricated from biologically derived amino acids or peptides. The ...

Qubits put new spin on magnetism: Boosting applications of quantum computers

2023-03-17

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., March 17, 2023 — Research using a quantum computer as the physical platform for quantum experiments has found a way to design and characterize tailor-made magnetic objects using quantum bits, or qubits. That opens up a new approach to develop new materials and robust quantum computing.

“With the help of a quantum annealer, we demonstrated a new way to pattern magnetic states,” said Alejandro Lopez-Bezanilla, a virtual experimentalist in the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos National Laboratory. ...

New combination of drugs works together to reduce lung tumors in mice

2023-03-17

LA JOLLA—(March 17, 2023) Cancer treatments have long been moving toward personalization—finding the right drugs that work for a patient’s unique tumor, based on specific genetic and molecular patterns. Many of these targeted therapies are highly effective, but aren’t available for all cancers, including non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) that have an LKB1 genetic mutation. A new study led by Salk Institute Professor Reuben Shaw and former postdoctoral fellow Lillian Eichner, now an assistant professor ...

Biomarkers show promise for identifying early risk of pancreatic cancer

2023-03-17

DURHAM, N.C. – A research team at Duke Health has identified a set of biomarkers that could help distinguish whether cysts on the pancreas are likely to develop into cancer or remain benign.

Appearing online March 17 in the journal Science Advances, the finding marks an important first step toward a clinical approach for classifying lesions on the pancreas that are at highest risk of becoming cancerous, potentially enabling their removal before they begin to spread.

If successful, the biomarker-based approach could address the biggest impediment to decreasing the ...

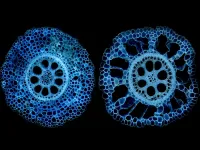

Discovery of root anatomy gene may lead to breeding more resilient corn crops

2023-03-17

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A new discovery, reported in a global study that encompassed more than a decade of research, could lead to the breeding of corn crops that can withstand drought and low-nitrogen soil conditions and ultimately ease global food insecurity, according to a Penn State-led team of international researchers.

In findings published March 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, the researchers identified a gene encoding a transcription factor – a protein useful for converting DNA into RNA – that triggers a genetic sequence responsible for the development of an important trait enabling corn roots ...

New study shows social media content opens new frontiers for sustainability science researchers

2023-03-17

With more than half of the world’s population active on social media networks, user-generated data has proved to be fertile ground for social scientists who study attitudes about the environment and sustainability.

But several challenges threaten the success of what's known as social media data science. The primary concern, according to a new study from an international research team, is limited access to data resulting from restrictive terms of service, shutdown of platforms, data manipulation, censorship and regulations.

The study, published online March ...

East and West Germans show preference for different government systems 30 years on

2023-03-17

Even after 27 years of reunification, East Germans are still more likely to be pro-state support than their Western counterparts, a new study published in the De Gruyter journal German Economic Review finds. Of the sample studied, 48% of respondents from the East said it was the government’s duty to support the family compared to 35% from the West.

The study led by Prof. Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln of Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany builds on her earlier work which evaluated results from the German Socio-Economic Panel, a regular survey of around 15,000 households. The survey has been running in the federal ...

NASA announces future launch for USU-led space weather mission

2023-03-17

NORTH LOGAN, UTAH - NASA has announced that the launch of the Utah State University Space Dynamics Laboratory and College of Science-led Atmospheric Waves Experiment, or AWE, is scheduled for December 2023. The NASA-funded instrument will launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station to the International Space Station.

AWE Principal Investigator Michael Taylor from USU’s College of Science leads a team of scientists that will provide new details about how the weather on Earth interacts with, and affects, space weather. To do that, the AWE instrument, measuring about 54 centimeters by 1 meter and weighing less than 57 kilograms, will peer into Earth’s ...

Quantum sensing in outer space: New NASA-funded research will build next-gen tech to better measure climate

2023-03-17

Texas Engineers are leading a multi-university research team that will build technology and tools to improve measurement of important climate factors by observing atoms in outer space.

They will focus on the concept of quantum sensing, which use quantum physics principles to potentially collect more precise data and enable unprecedented science measurements. These sensors could help satellites in orbit collect data about how atoms react to small changes in their environment, and using that to infer the ...