(Press-News.org) Dopamine, a brain chemical long associated with pleasure, motivation and reward-seeking, also appears to play an important role in why exercise and other physical efforts feel “easy” to some people and exhausting to others, according to results of a study of people with Parkinson’s disease led by Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers. Parkinson’s disease is marked by a loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain over time.

The findings, published online April 1 in NPG Parkinson’s Disease, could, the researchers say, eventually lead to more effective ways to help people establish and stick with exercise regimens, new treatments for fatigue associated with depression and many other conditions, and a better understanding of Parkinson’s disease.

“Researchers have long been trying to understand why some people find physical effort easier than others,” says study leader Vikram Chib, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and research scientist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute. “This study’s results suggest that the amount of dopamine availability in the brain is a key factor.”

Chib explains that after a bout of physical activity, people’s perception and self-reports of the effort they expended varies, and also guides their decisions about undertaking future exertions. Previous studies have shown that people with increased dopamine are more willing to exert physical effort for rewards, but the current study focuses on dopamine’s role in people’s self-assessment of effort needed for a physical task, without the promise of a reward.

For the study, Chib and his colleagues from Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Kennedy Krieger Institute recruited 19 adults diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a condition in which neurons in the brain that produce dopamine gradually die off, causing unintended and uncontrollable movements such as tremors, fatigue, stiffness and trouble with balance or coordination.

In Chib’s lab, 10 male volunteers and nine female volunteers with an average age of 67 were asked to perform the same physical task — squeezing a hand grip equipped with a sensor — on two different days within four weeks of each other. On one of the days, the patients were asked to take their standard, daily synthetic dopamine medication as they normally would. On the other, they were asked not to take their medication for at least 12 hours prior to performing the squeeze test.

On both days, the patients were initially taught to squeeze a grip sensor at various levels of defined effort, and then were asked to squeeze and report how many units of effort they put forth.

When the participants had taken their regular synthetic dopamine medication, their self-assessments of units of effort expended were more accurate than when they hadn’t taken the drug. They also had less variability in their efforts, showing accurate squeezes when the researchers cued them to squeeze at different levels of effort.

In contrast, when the patients hadn’t taken the medication, they consistently over-reported their efforts — meaning they perceived the task to be physically harder — and had significantly more variability among grips after being cued.

In another experiment, the patients were given a choice between a sure option of squeezing with a relatively low amount of effort on the grip sensor or flipping a coin and taking a chance on having to perform either no effort or a very high level of effort. When these volunteers had taken their medication, they were more willing to take a chance on having to perform a higher amount of effort than when they didn’t take their medication.

A third experiment offered participants the choice between getting a small amount of guaranteed money or, with the flip of a coin, getting either nothing or a higher amount of money. Results showed no difference in the subjects on days when they took their medication and when they did not. This result, researchers say, suggests that dopamine’s influence on risk-taking preferences is specific to physical effort-based decision-making.

Together, Chib says, these findings suggest that dopamine level is a critical factor in helping people accurately assess how much effort a physical task requires, which can significantly affect how much effort they’re willing to put forth for future tasks. For example, if someone perceives that a physical task will take an extraordinary amount of effort, they may be less motivated to do it.

Understanding more about the chemistry and biology of motivation could advance ways to motivate exercise and physical therapy regimens, Chib says. In addition, inefficient dopamine signaling could help explain the pervasive fatigue present in conditions such as depression and long COVID, and during cancer treatments. Currently, he and his colleagues are studying dopamine’s role in clinical fatigue.

Other researchers who participated in this study include Purnima Padmanabhan, Agostina Casamento-Moran, and Alexander Pantelyat of Johns Hopkins; Ryan Roemmich of Johns Hopkins and the Kennedy Krieger Institute; and Anthony Gonzalez of the Kennedy Krieger Institute.

This work was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (R01HD097619), the National Institutes of Mental Health (R56MH113627 and R01MH119086) and the National Institute of Aging (R21AG059184).

DOI: 10.1038/s41531-023-00490-4

END

Whether physical exertion feels ‘easy’ or ‘hard’ may be due to dopamine levels, study suggests

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Open-label placebo improved outcomes for people in treatment for opioid use disorder

2023-04-12

BOSTON – There were more than 100,000 reported deaths from opioid overdoses in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methadone treatment remains one of the most reliable means of treating opioid use disorder, with success rates reportedly ranging from 60 to 90 percent for patients who stick with the long-term regimen. Adherence, though, remains a challenge.

In a novel randomized clinical trial published in JAMA Network Open, senior author Ted J. Kaptchuk at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center ...

New agreement will help researchers study metal worlds of M-type asteroids

2023-04-12

ORLANDO, April 12, 2023 – A University of Central Florida researcher will be using the newly constructed Two-meter Twin Telescope (TTT) in the Canary Islands, Spain, to study metal-rich M-type asteroids.

The work can inform the study of asteroids like 16 Psyche, an M-type, or metal, asteroid NASA is launching a mission in October 2023 to visit.

The M-type asteroids offer both high concentrations of metals that could be harnessed to make structures in space as well as clues to the formation of ...

Innovative healthcare extension project enables community-based physicians to diagnose autism in young children

2023-04-12

As the number of children in need of access to timely evaluation and intervention for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) continues to rise, new research is showing how barriers to diagnoses and treatment can be reduced through an innovative training program first developed at the University of Missouri.

ASD can be identified and diagnosed in young children by a well-trained clinician, and early diagnosis is vital to quickly establishing access to evidence-based therapies and interventions. However, long specialty center waitlists, distance, and ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights: AACR 2023 Special Edition

2023-04-12

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

This special edition features presentations by MD Anderson researchers at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2023. In addition to these studies, forthcoming press releases will feature groundbreaking research on perioperative immunotherapy for operable lung cancer (Abstract CT005), ...

Scientists sequence genome of little skate, the stingray’s cousin

2023-04-12

Rutgers geneticists, working with an international team of scientists, have conducted the most comprehensive sequencing yet of the complete DNA sequence of the little skate – which, like its better-known cousin, the stingray, has long been viewed as enigmatic because of its shape.

The scientists, writing in Nature, reported that by studying the intricacies of Leucoraja erinacea’s genome, they have gained a far better understanding of how the fish evolved from its ancestor – which possessed a much narrower body – over a period of 300 million years to become a flat, winged bottom-dweller.

“We ...

The brain’s support cells may play a key role in OCD

2023-04-12

A type of cell usually characterized as the brain’s support system appears to play an important role in obsessive-compulsive disorder-related behaviors, according to new UCLA Health research published April 12 in Nature.

The new clue about the brain mechanisms behind OCD, a disorder that is incompletely understood, came as a surprise to researchers. They originally sought to study how neurons interact with star-shaped “helper” cells known as astrocytes, which are known to provide support and protection to neurons.

However, ...

Pragmatica-Lung Study, a streamlined model for future cancer clinical trials, begins enrolling patients

2023-04-12

The National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has helped launch a phase 3 randomized clinical trial (NCT05633602) of a two-drug combination to treat patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Called the Pragmatica-Lung Study (or S2302), this is one of the first NCI-supported clinical trials to use a trial design that removes many of the barriers that prevent people from joining clinical trials. This “pragmatic” approach aims to increase accessibility ...

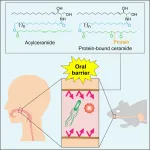

Oral barrier is similar in ceramide composition to skin barrier

2023-04-12

Acylceramides and protein-bound ceramides are vital for the formation of the oral barrier in mice, similar to their role in skin, protecting from infection.

The skin is the body’s first line of defense against the environment, particularly against pathogens, chemicals, and allergens. It is now known that a class of biological molecules called acylceramides and their metabolites, protein-bound ceramides, are essential to the formation of this barrier. The outermost tissues of the mouth are closely related to the skin and have similar functions—an oral barrier. However, little ...

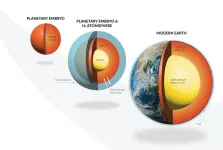

How did Earth get its water?

2023-04-12

Washington, DC—Our planet’s water could have originated from interactions between the hydrogen-rich atmospheres and magma oceans of the planetary embryos that comprised Earth’s formative years, according to new work from Carnegie Science’s Anat Shahar and UCLA’s Edward Young and Hilke Schlichting. Their findings, which could explain the origins of Earth’s signature features, are published in Nature.

For decades, what researchers knew about planet formation was based ...

Effect of smartphone app home monitoring after oncologic surgery on quality of recovery

2023-04-12

About The Study: In this randomized clinical trial, postoperative follow-up for patients undergoing breast reconstruction and gynecologic oncology surgery using smartphone app–assisted monitoring led to improved quality of recovery and equal satisfaction with care compared with conventional in-person follow-up.

Authors: Claire Temple-Oberle, M.D., M.Sc., of the University of Calgary in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0616)

Editor’s ...