(Press-News.org) It’s extremely difficult to study the biological basis of psychiatric disorders, in part because researchers can’t easily collect brain cells from living people to study in the laboratory. Now, University of Utah Health scientists have developed a way around that.

The researchers grew three-dimensional structures, called “organoids”, derived from blood cells donated by a patient with pediatric bipolar disorder and by several family members. The approach identified significant molecular changes linked to the psychiatric condition.

The results, reported in Molecular Psychiatry, suggest that structural changes in the brain seen in people with pediatric bipolar disorder may arise from dysfunction in a gene that assists with cellular signaling. The findings also demonstrate that lab-grown organoids can provide insights into causes of psychiatric disorders.

“If we don't have animal models, there is no way to look for therapies in preclinical studies. It's a huge challenge,” says Alex Shcheglovitov, Ph.D., assistant professor of neurobiology at University of Utah and senior author of the study. Graduate student Guang Yang was first author of the paper. “There's definitely a need to develop new innovative models to study the cellular and molecular mechanisms disrupted in pediatric bipolar disorder.”

Changes in the bipolar brain

Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric condition that causes extreme mood swings, fluctuating between depression and mania. When the disease arises in childhood, it can be a sign that a strong genetic component is involved. Shcheglovitov and colleagues reasoned that such a complex disorder required an innovative, multidisciplinary approach to study it.

Melissa Lopez-Larson, M.D., psychiatrist and a co-author of the paper, has done brain imaging of children with pediatric bipolar disorder and their unaffected family members to look at how the disease changes the connections between brain regions. In people with bipolar disorder, an imaging technique called functional MRI, or fMRI, reveals changes in the brain’s resting activity, though it’s not known what causes these changes.

To learn more, Lopez-Larson collaborated with neurobiologists Shcheglovitov and Yang, and radiologists, geneticists, and psychiatrists at U of U Health and Huntsman Mental Health Institute, to combine imaging data with an in-depth analysis of patient cells at the molecular level.

Yang started with blood cells donated from a 9-year-old boy with bipolar disorder, his parents, and an unaffected sibling. By cultivating the cells under the right conditions, Yang induced them to become stem cells, which he then grew into neurons. The cells were then converted into structured clusters, called organoids, using an approach recently developed by the Shcheglovitov group. Organoids mimic early aspects of human brain development and allow researchers to study communication between neurons, similar to interactions that occur in the living brain.

“What these organoids allow us to do is to model certain developmental stages associated with certain brain regions,” says Shcheglovitov. “In our case, the are organoids are more like the frontal part of the fetal human brain.”

In search of a cause

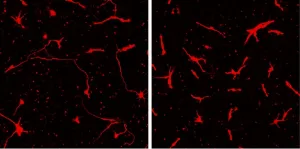

To find root causes of the disorder, Yang ran tests to determine how cells from the child with bipolar disorder differed from his family members’. Yang discovered that the patient had a change in a gene called PLXNB1, which had previously been associated with psychiatric disease. He also found that cells looked different: neuronal processes called “neurites” were shorter. These long tendrils normally forge important connections with neighboring cells.

Adding normal PLXNB1 into the patient’s cells allowed the neurites to grow to normal size, confirming the mutation in PLXNB1 caused the changes in neurite growth. “This is super exciting,” says Shcheglovitov. “This suggests that, potentially, using gene-based therapy, or another treatment that targets the PLXNB1 pathway, could be therapeutically relevant for patients with pediatric bipolar disorder.”

Before the results can lead to new therapies, researchers will need to conduct larger studies to determine whether other people with this disorder share these same differences. The power of this study, Lopez-Larson says, was combining multiple technologies to create a robust picture of what’s happening in the brain.

“The fMRI showed that the brain connections are atypical, at least in this particular child. And we also found that was true with the genetic piece as well,” Lopez-Larson says. “We were able to use different kinds of advanced technologies that revealed the same thing in different ways.”

# # #

In addition to Shcheglovitov, Yang, and Lopez-Larson, additional coauthors were from the following University of Utah departments and institutes: H.M. Arif Ullah and Mark Liebowitz (Neurobiology), Ethan Parker (Bioengineering), Bushra Gorsi and Mark Yandell (Human Genetics), Colin Maguire (Utah Clinical & Translational Research Institute), Jace King and Jeffrey Anderson (Radiology) and Hilary Coon (Psychiatry, Huntsman Mental Health Institute).

The research was made possible by support from the Utah Neuroscience Initiative and Utah Genome Project and published as, “Neurite outgrowth deficits caused by rare PLXNB1 mutation in pediatric bipolar disorder.”

About University of Utah Health

University of Utah Health provides leading-edge and compassionate care for a referral area that encompasses Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and much of Nevada. A hub for health sciences research and education in the region, U of U Health has a $458 million research enterprise and trains scientists, the majority of Utah’s physicians, and health care providers at its Colleges of Health, Nursing, and Pharmacy and Schools of Dentistry and Medicine. With more than 20,000 employees, the system includes 12 community clinics and five hospitals. U of U Health is recognized nationally as a transformative health care system and provider of world-class care.

END

New technique allows researchers to dig into molecular causes of pediatric bipolar disorder

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

COVID-19 pandemic will disrupt cancer reporting for years to come

2023-04-12

Key takeaways:

American College of Surgeons research published in JAMA Surgery reveals the complexities and variations that occurred in cancer reporting in the National Cancer Database (NCDB) because of the pandemic.

The number of reported cancer cases in NCDB declined by 14.4% compared with prior years, representing more than 200,000 cancer cases that were not diagnosed and/or treated at accredited facilities.

Research offers guidance to centers across the country on how to interpret data from 2020 and onwards.

CHICAGO: New research from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) outlines significant ways that the COVID-19 pandemic destabilized usual patterns of cancer care as reported ...

Is the language you speak tied to outcome after stroke?

2023-04-12

MINNEAPOLIS – Studies have shown that Mexican Americans have worse outcomes after a stroke than non-Hispanic white Americans. A new study looks at whether the language Mexican American people speak is linked to how well they recover after a stroke. The study is published in the April 12, 2023, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Our study found that Mexican American people who spoke only Spanish had worse neurologic outcomes three months after having a stroke than Mexican American people who spoke only English or were bilingual,” said study author ...

Archaeological sites at risk from coastal erosion on the Cyrenaican coast, Libya

2023-04-12

Archaeological sites along the Libyan shoreline are at risk of being damaged or lost due to increasing coastal erosion, according to a study published April 12, 2023 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Kieran Westley and Julia Nikolaus of Ulster University, UK and colleagues.

The Cyrenaican coast of Eastern Libya, stretching from the Gulf of Sirte to the current Egypt-Libya border, has a long history of human occupation back to the Palaeolithic era, and it therefore hosts numerous important and often ...

Poor family cohesion is associated with long-term psychological impacts in bereaved teenagers

2023-04-12

The death of a parent can affect the health and well-being of children and adolescents, including higher risk of depression. A study published in PLOS ONE by Dröfn Birgisdóttir at Lund University, Lund, Sweden and colleagues suggests poor family cohesion is associated with long-term psychological symptoms among bereaved youth.

Parentally bereaved children are at increased risk for mental illness including depression, anxiety, suicide attempts, and self-injurious behaviors. However, the relationship ...

The stripes of the Lesser Pacific Striped Octopus are as unique as our own fingerprints, enabling scientists to track individuals as they grow

2023-04-12

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0265292

Article Title: Individually unique, fixed stripe configurations of Octopus chierchiae allow for photoidentification in long-term studies

Author Countries: USA

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work. END ...

Most retail cannabis may be less potent than claimed, with THC being at least 15% less potent than reported on the label in around 70% of products sampled in Colorado

2023-04-12

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0282396

Article Title: Uncomfortably high: Testing reveals inflated THC potency on retail Cannabis labels

Author Countries: USA

Funding: Headspace Sensory LLC provided funding for purchase of 13 of the 23 Cannabis samples that were included as part of another study [47], but had no other involvement in this study. All other funding was provided by the McGlaughlin Lab at the University of Northern Colorado and by the first author. Mile High Labs provided support for this study in the form of salaries for VJ and JH. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ ...

New 52 million-year-old bat species discovered in Wyoming, US, is the oldest bat skeleton known

2023-04-12

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0283505

Article Title: The oldest known bat skeletons and their implications for Eocene chiropteran diversification

Author Countries: The Netherlands, USA

Funding: 1) Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Fund of the American Museum of Natural History (TBR) https://www.amnh.org/research/richard-gilder-graduate-school/academics-and-research/fellowship-and-grant-opportunities/research-grants-and-graduate-student-exchange-fellowships/roosevelt-memorial-fund 2) ...

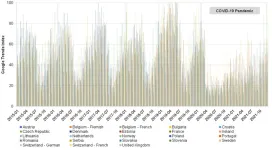

Google Trends reveal how the spread of chickenpox may have been suppressed during the COVID-19 pandemic

2023-04-12

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0283465

Article Title: Impact assessment of immunization and the COVID-19 pandemic on varicella across Europe using digital epidemiology methods: A descriptive study

Author Countries: Sweden, Lithuania, Ireland, USA, Spain

Funding: Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (MSD). We confirm that the funder provided support in the form of salaries for Ugne Sabale, Ligita Jarmale, Janice Murtagh, Manjiri Pawaskar, and Goran Bencina, but did not have any additional ...

Got milk? The ancient Tibetans did, according to study

2023-04-12

New research into ancient populations that resided on the Tibetan Plateau has found that dairy pastoralism was being practiced far earlier than previously thought and may have been key to long-term settlement of the region’s extreme environment.

Professor Michael Petraglia, Director of Griffith’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, was part of the international research team that set out to understand how prehistoric populations adapted to the vast, agriculturally poor highlands of the Tibetan Plateau.

The research, ...

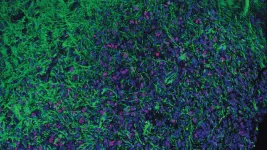

From tragedy, a new potential cancer treatment

2023-04-12

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a lethal pediatric brain cancer that often kills within a year of diagnosis. Surgery is almost impossible because of the tumors’ location. Chemotherapy has debilitating side effects. New treatment options are desperately needed.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Adrian Krainer is best known for his groundbreaking research on antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs)—molecules that can control protein levels in cells. His efforts led to Spinraza®, ...