(Press-News.org) In tropical regions of the planet, savannas and forests often coexist in the same area and are exposed to the same climate. An example is the Cerrado, a Brazilian biome that includes several types of vegetation, from broad-leaved and sclerophyllous in dense woodland or shrubland (cerrado sensu stricto) to semi-evergreen in closed-canopy forest (cerradão), as well as grassland with scattered shrubs (campo sujo) and even semi-deciduous seasonal forest.

Areas of cerradão develop in the absence of fire, in both poor and moderately fertile soil (dystrophic to mesotrophic).

This coexistence intrigues botanists and ecologists since savannas and forests are home to different species and have different dynamics and functions. Savannas are dense and highly flammable grasslands that burn fairly frequently, with a direct impact on other types of vegetation.

Forests, on the other hand, have a broad, mostly continuous canopy that provides shade for undergrowth, bushes and smaller trees, and prevents the growth of flammable grass.

Savanna species evolved over millions of years in the presence of fire and have thick bark to protect them. After burning, they form new branches and leaves from asexual buds called gemmae.

A study conducted at the Santa Bárbara Ecological Station, an environmental protection unit in São Paulo state, investigated how much bark is produced by savanna and forest species in the Cerrado, whether savanna species that produce more bark also protect their gemmae more effectively, and whether generalist species (occurring in both savanna and forest) produce different amounts of bark depending on the environment in which they grow. An article on the study is published in the journal Annals of Botany.

The principal investigator for the study was Alessandra Fidelis, a professor in the Department of Biodiversity at São Paulo State University’s Rio Claro Institute of Biosciences (IBRC-UNESP).

The first author of the article is Marco Antonio Chiminazzo, a PhD candidate at IBRC-UNESP.

The other co-authors are Aline Bombo, a postdoctoral fellow at IBRC-UNESP, and Tristan Charles-Dominique, a researcher at the Sorbonne in Paris and the University of Montpellier, both in France.

“We observed that savanna species produce about three times as much bark as forest species, while generalist species are intermediate, producing more bark in savanna than forest areas. This ability to adjust bark production to the environment is known as phenotypic plasticity and may be a deliberate strategy. We also found that species that produce more bark protect their gemmae and internal tissues better,” Chiminazzo told Agência FAPESP.

“Our study shows that fire is an important factor for savanna-type vegetation in the Cerrado, promoting the woody species that can cope with this disturbance and couldn’t live in shady forest areas.”

The study provides evidence that strongly supports those who advocate the carefully controlled use of fire to manage the savanna areas of the Cerrado. Properly managed fire requires zoning and a timetable. Zoning establishes a mosaic framework within which to burn designated areas rotationally in accordance with the timetable.

“Plant species in the Cerrado have adapted to fire, producing thick bark and strongly protecting their gemmae. These traits, which are the result of a long evolutionary process, enable them to survive fires and regenerate after burning,” said Fidelis, who is Chiminazzo’s thesis advisor.

Remainder

Located in the municipality of Águas de Santa Bárbara, the ecological station where the study was conducted is an important native Cerrado remainder in São Paulo state and contains all the different types of savanna and forest found in the biome. “We sampled shrub and tree species from four different types of vegetation with varying frequencies of burning and light availability. We investigated the amount of bark they produce as they develop and how they protect their gemmae against the effects of fire. We then separated the species according to the environment they prefer to inhabit, forming three groups: savanna specialists, forest specialists and generalists [capable of growing in both],” Chiminazzo said.

Future research should set out to understand how and why certain species can adjust bark production, whereas others cannot, he added. “In the context of climate change and changes in fire regimes, garnering deeper knowledge of these species offers a major opportunity to understand and predict which organisms will be more or less endangered, in accordance with their ability to adapt to varying environmental conditions,” he said.

The study was supported by FAPESP via a Young Investigator Grant awarded to Fidelis. In addition, Chiminazzo received a master’s scholarship and a doctoral scholarship.

About São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP)

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. FAPESP is aware that the very best research can only be done by working with the best researchers internationally. Therefore, it has established partnerships with funding agencies, higher education, private companies, and research organizations in other countries known for the quality of their research and has been encouraging scientists funded by its grants to further develop their international collaboration. You can learn more about FAPESP at www.fapesp.br/en and visit FAPESP news agency at www.agencia.fapesp.br/en to keep updated with the latest scientific breakthroughs FAPESP helps achieve through its many programs, awards and research centers. You may also subscribe to FAPESP news agency at http://agencia.fapesp.br/subscribe.

END

Trees in savanna areas of Cerrado produce three times more bark than species in forest areas

The mechanism has resulted from evolution over millions of years to protect the buds that enable plants to survive fire. A study conducted in an environmental protection unit can contribute to strategies for mitigating the effects of climate change

2023-04-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Wayne State researcher receives $1.95 million NIH grant to study impact of inositol homeostasis on essential cellular functions

2023-04-14

DETROIT – A researcher from Wayne State University’s Department of Biological Sciences has received a five-year, $1.95 million grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health to identify mechanisms that regulate inositol synthesis in mammalian cells and determine the cellular consequences of inositol depletion.

Inositol is a type of sugar that is essential for the viability of eukaryotic cells. Myo-inositol is the precursor of all inositol compounds, which play pivotal roles in cell signaling and metabolism. Consistent with its importance, a disturbance of inositol homeostasis ...

Head and neck, breast cancer research highlights University of Cincinnati AACR abstracts

2023-04-14

University of Cincinnati Cancer Center researchers will present more than a dozen abstracts at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2023, held in Orlando, Florida, April 14-19, including findings that could advance treatments for head and neck and breast cancers.

Enzyme shows promise as target to treat HPV negative head and neck cancer

Vinita Takiar’s lab in UC’s Department of Radiation Oncology studies how to improve radiation therapy for head and neck cancer patients.

Julianna Korns, a doctoral student working in Takiar’s lab, and her colleagues study an enzyme called Plk1 that allows healthy cells to divide ...

Scientists develop new way to measure wind

2023-04-14

Wind speed and direction provide clues for forecasting weather patterns. In fact, wind influences cloud formation by bringing water vapor together. Atmospheric scientists have now found a novel way of measuring wind – by developing an algorithm that uses data from water vapor movements. This could help predict extreme events like hurricanes and storms.

A study published by University of Arizona researchers in the journal Geophysical Research Letters provides, for the first time, data on the vertical distribution of horizontal winds ...

Ancient DNA reveals the multiethnic structure of Mongolia’s first nomadic empire

2023-04-14

Long obscured in the shadows of history, the world’s first nomadic empire - the Xiongnu - is at last coming into view thanks to painstaking archaeological excavations and new ancient DNA evidence. Arising on the Mongolian steppe 1,500 years before the Mongols, the Xiongnu empire grew to be one of Iron Age Asia’s most powerful political forces - ultimately stretching its reach and influence from Egypt to Rome to Imperial China. Economically grounded in animal husbandry and dairying, the Xiongnu were famously nomadic, building their empire on the backs of horses. ...

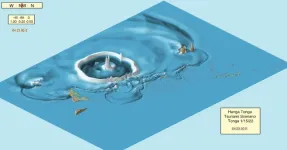

2022 Tongan volcanic explosion was largest natural explosion in over a century, new study finds

2023-04-14

The 2022 eruption of a submarine volcano in Tonga was more powerful than the largest U.S. nuclear explosion, according to a new study led by scientists at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science and the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation.

The 15-megaton volcanic explosion from Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, one of the largest natural explosions in more than a century, generated a mega-tsunami with waves up to 45-meters high (148 feet) along the coast of Tonga’s Tofua Island and waves up to 17 meters (56 feet) on Tongatapu, ...

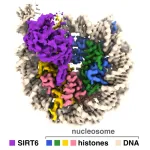

How does an aging-associated enzyme access our genetic material?

2023-04-14

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — New research provides insight into how an enzyme that helps regulate aging and other metabolic processes accesses our genetic material to modulate gene expression within the cell. A team led by Penn State researchers have produced images of a sirtuin enzyme bound to a nucleosome—a tightly packed complex of DNA and proteins called histones—showing how the enzyme navigates the nucleosome complex to access both DNA and histone proteins and clarifying how it functions in humans and other animals.

A paper describing the results appears April 14 in the journal ...

Aston University develops software to untangle genetic factors linked to shared characteristics among different species

2023-04-14

Has potential to help geneticists investigate vital issues such as antibacterial resistance

Will untangle the genetic components shared due to common ancestry from the ones shared due to evolution

The work is result of a four-year international collaboration.

Aston University has worked with international partners to develop a software package to help scientists answer key questions about genetic factors associated with shared characteristics among different species.

Called CALANGO (comparative analysis with annotation-based genomic ...

Single-use surgical items contribute two-thirds of carbon footprint of products used in common operations

2023-04-14

A new analysis of the carbon footprint of products used in the five most common surgical operations carried out in the NHS in England shows that 68% of carbon contributions come from single-use items, such as single-use gowns, patient drapes and instrument table drapes. Published by the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, the analysis highlights significant carbon contributors were the production of single use items and their waste disposal, together with processes for decontaminating reusable products.

Researchers ...

Study: Anti-obesity medications could be sold for lower prices

2023-04-14

ROCKVILLE, Md.—New research shows that several anti-obesity medications could be manufactured and profitability sold worldwide at far lower estimated lower prices compared to their high costs, according to a new study in Obesity, The Obesity Society’s (TOS) flagship journal.

“Access to medicine is a fundamental element of the human right to health. While the obesity pandemic grows, especially amongst low-income communities, effective medical treatments remain inaccessible for millions in need. Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective anti-obesity medications, ...

Offering medications for opioid addiction to incarcerated individuals leads to decrease in overdose deaths

2023-04-14

BOSTON – New research from Boston Medical Center concluded that offering medications to treat opioid addiction in jails and prisons leads to a decrease in overdose deaths. Published in JAMA Network Open, the study also found that treating opioid addiction during incarceration is cost-effective in terms of healthcare costs, incarceration costs, and deaths avoided.

Overdoses kill more than 100,000 people per year in America and this number continues to increase every year. People with addiction are more likely to be incarcerated than treated, with those from communities of color who use drugs more likely to be incarcerated than ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] Trees in savanna areas of Cerrado produce three times more bark than species in forest areasThe mechanism has resulted from evolution over millions of years to protect the buds that enable plants to survive fire. A study conducted in an environmental protection unit can contribute to strategies for mitigating the effects of climate change