For more than half a century, the Tully monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium), an enigmatic animal that lived about 300 million years ago, has confounded paleontologists, with its strange anatomy making it difficult to classify. Recently, a group of researchers proposed a hypothesis that Tullimonstrum was a vertebrate similar to cyclostomes (jawless fish like lamprey and hagfish). If it was, then the Tully monster would potentially fill a gap in the evolutionary history of early vertebrates. Studies so far have both supported and rejected this hypothesis. Now, using 3D imaging technology, a team in Japan believes it has found the answer after uncovering detailed characteristics of the Tully monster which strongly suggest that it was not a vertebrate. However, its exact classification and what type of invertebrate it was is still to be decided.

In the 1950s, Francis Tully was enjoying his hobby fossil hunting in a site known as Mazon Creek Lagerstätte in the U.S. state of Illinois, when he discovered what would later become known as the Tully monster. This 15-centimeter (on average), 300-million-year-old marine “monster” turned out to be an enigma, as ever since its discovery researchers have debated where it fits in the classification of living things (its taxonomic position). Unlike dinosaur bones and hard-shelled creatures that are often found as fossils, the Tully monster was soft-bodied. The Mazon Creek Lagerstätte is one of the few places in the world where the conditions were just right for imprints of these marine animals to be captured in detail in the underwater mud, before they could decay. In 2016, a group of scientists in the US proposed a hypothesis that the Tully monster was a vertebrate. If this was the case, then it could be a missing piece of the puzzle on how vertebrates evolved.

Despite considerable effort, studies both supporting and rejecting this hypothesis have been published in recent years, and so a consensus had not been reached. However, new research by a team from the University of Tokyo and Nagoya University may have finally brought an end to the debate. “We believe that the mystery of it being an invertebrate or vertebrate has been solved,” said Tomoyuki Mikami, a doctoral student in the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo at the time of the study and currently a researcher at the National Museum of Nature and Science. “Based on multiple lines of evidence, the vertebrate hypothesis of the Tully monster is untenable. The most important point is that the Tully monster had segmentation in its head region that extended from its body. This characteristic is not known in any vertebrate lineage, suggesting a nonvertebrate affinity.”

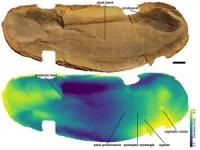

The team studied more than 150 fossilized Tully monsters and over 70 other varied animal fossils from Mazon Creek. With the aid of a 3D laser scanner, they created color-coded, three-dimensional maps of the fossils which showed the tiny irregularities which existed on their surface through color variation. X-ray micro-computed tomography (which uses X-rays to create cross sections of an object so that a 3D model can be created), was also used to look at its proboscis (an elongated organ located in the head). This 3D data showed that features previously used to identify the Tully monster as a vertebrate were not actually consistent with those of vertebrates.

Although the researchers are confident from this study that the Tully monster was not a vertebrate, the next step of the investigation will be to answer what group of organisms it does belong to, possibly a nonvertebrate chordate (like a fishlike animal known as a lancelet) or some sort of protostome (a diverse group of animals containing, for example, insects, roundworms, earthworms and snails) with radically modified morphology.

Problematic fossils like the Tully monster highlight the challenge of piecing together the dynamic history of Earth and the diverse organisms that have inhabited it. “There were many interesting animals that were never preserved as fossils,” Mikami said. “In this sense, research on the fossils from Mazon Creek is important because it provides paleontological evidence that cannot be obtained from other sites. More and more research is needed to extract important clues from Mazon Creek fossils to understand the evolutionary history of life.”

#####

Paper Title:

Tomoyuki Mikami, Takafumi Ikeda, Yusuke Muramiya, Tatsuya Hirasawa, Wataru Iwasaki. Three-dimensional anatomy of the Tully monster casts doubt on its presumed vertebrate affinities Palaeontology 2023. DOI: 10.1111/pala.12646

Funding:

This research was supported by the Masason Foundation, Fujiwara Natural History Foundation, JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers 18J21859 and 22J01214), and the World-Leading Innovative Graduate Study Program for Life Science and Technology.

Useful Links:

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

Graduate School of Frontier Sciences: https://www.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/index.html

Research Contacts:

Professor Wataru Iwasaki

Graduate School of Frontier Sciences

Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-0882

Email:iwasaki@k.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Tel.: +81-4-7136-3679

Tomoyuki Mikami

National Museum of Nature and Science

Address: 4-1-1, Amakubo, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki 305-0005

Email: mikami@kahaku.go.jp

Tel: +81-29-853-8263

Press contact:

Mrs. Nicola Burghall

Public Relations Group, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan

press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

END