(Press-News.org) For more than 20 years, scientists have relied on the human reference genome, a consensus genetic sequence, as a standard against which to compare other genetic data. Used in countless studies, the reference genome has made it possible to identify genes implicated in specific diseases and trace the evolution of human traits, among other things.

But it has always been a flawed tool. One of its biggest problems is that about 70 percent of its data came from a single man of predominantly African-European background whose DNA was sequenced during the Human Genome Project, the first effort to capture all of a person’s DNA. As a result, it can tell us little about the 0.2 to one percent of genetic sequence that makes each of the seven billion people on this planet different from each other, creating an inherent bias in biomedical data believed to be responsible for some of the health disparities affecting patients today. Many genetic variants found in non-European populations, for instance, aren’t represented in the reference genome at all.

For years, researchers have called for a resource more inclusive of human diversity with which to diagnose diseases and guide medical treatments. Now scientists with the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium have made groundbreaking progress in characterizing the fraction of human DNA that varies between individuals. As they recently published in Nature, they’ve assembled genomic sequences of 47 people from around the world into a so-called pangenome in which more than 99 percent of each sequence is rendered with high accuracy.

Layered upon each other, these sequences revealed nearly 120 million DNA base pairs that were previously unseen.

While it’s still a work in progress, the pangenome is public and can be used by scientists around the world as a new standard human genome reference, says The Rockefeller University’s Erich D. Jarvis, one of the primary investigators.

“This complex genomic collection represents significantly more accurate human genetic diversity than has ever been captured before,” he says. “With a greater breadth and depth of genetic data at their disposal, and greater quality of genome assemblies, researchers can refine their understanding of the link between genes and disease traits, and accelerate clinical research.”

Sourcing diversity

Completed in 2003, the first draft of the human genome was relatively imprecise, but it became sharper over the years thanks to filled-in gaps, corrected errors, and advancing sequencing technology. Another milestone was reached last year, when the final eight percent of the genome—mainly tightly coiled DNA that doesn’t code for protein and repetitive DNA regions—was finally sequenced.

Despite this progress, the reference genome remained imperfect, especially with respect to the critical 0.2 to one percent of DNA representing diversity. The Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC), a government-funded collaboration between more than a dozen research institutions in the United States and Europe, was launched in 2019 to address this problem.

At the time, Jarvis, one of the consortium’s leaders, was honing advanced sequencing and computational methods through the Vertebrate Genomes Project, which aims to sequence all 70,000 vertebrate species. His and other collaborating labs decided to apply these advances for high-quality diploid genome assemblies to revealing the variation within a single vertebrate: Homo sapiens.

To collect a diversity of samples, the researchers turned to the 1000 Genomes Project, a public database of sequenced human genomes that includes more than 2500 individuals representing 26 geographically and ethnically varied populations. Most of the samples come from Africa, home to the planet’s largest human diversity.

“In many other large human genome diversity projects, the scientists selected mostly European samples,” Jarvis says. “We made a purposeful effort to do the opposite. We were trying to counteract the biases of the past.”

It’s likely that gene variants that could inform our knowledge of both common and rare diseases can be found among these populations.

Mom, dad, and child

But to broaden the gene pool, the researchers had to create crisper, clearer sequences of each individual–and the approaches developed by members of the Vertebrate Genome Project and associated consortiums were used to solve a longstanding technical problem in the field.

Every person inherits one genome from each parent, which is how we end up with two copies of every chromosome, giving us what’s known as a diploid genome. And when a person’s genome is sequenced, teasing apart parental DNA can be challenging. Older techniques and algorithms have routinely made errors when merging parental genetic data for an individual, resulting in a cloudy view. “The differences between mom’s and dad’s chromosomes are bigger than most people realize,” Jarvis says. “Mom may have 20 copies of a gene and dad only two.”

With so many genomes represented in a pangenome, that cloudiness threatened to develop into a thunderstorm of confusion. So the HPRC homed in a method developed by Adam Phillippy and Sergey Koren at the National Institutes of Health on parent-child “trios”—a mother, a father, and a child whose genomes had all been sequenced. Using the data from mom and dad, they were able to clear up the lines of inheritance and arrive at a higher-quality sequence for the child, which they then used for pangenome analysis.

New variations

The researchers’ analysis of 47 people yielded 94 distinct genome sequences, two for each set of chromosomes, plus the sex Y chromosome in males.

They then used advanced computational techniques to align and layer the 94 sequences. Of the 120 million DNA base pairs that were previously unseen or in a different location than they were noted to be in the previous reference, about 90 million derive from structural variations, which are differences in people’s DNA that arise when chunks of chromosomes are rearranged—moved, deleted, inverted, or with extra copies from duplications.

It’s an important discovery, Jarvis notes, because studies in recent years have established that structural variants play a major role in human health, as well as in population-specific diversity. “They can have dramatic effects on trait differences, disease, and gene function,” he says. “With so many new ones identified, there's going to be a lot of new discoveries that weren’t possible before.”

Filling gaps

The pangenome assembly also fills in gaps that were due to repetitive sequences or duplicated genes. One example is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a cluster of genes that code proteins on the surface of cells that help the immune system recognize antigens, such as those from the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

“They’re really important, but it was impossible to study MHC diversity using the older sequencing methods,” Jarvis says. “We're seeing much greater diversity than we expected. This new information will help us understand how immune responses against specific pathogens vary among people.” It could also lead to better methods to match organ transplant donors with and patients, or identify people at risk for developing autoimmune disease.

The team has also uncovered surprising new characteristics of centromeres, which lie at the cruxes of chromosomes and conduct cell division, pulling apart as cells duplicate. Mutations in centromeres can lead to cancers and other diseases.

Despite having highly repetitive DNA sequences, “centromeres are so diverse from one haplotype to another, that they can account for more than 50 percent of the genetic differences between people or maternal and paternal haplotypes even within one individual,” Jarvis says. “The centromeres seem to be one of the most rapidly evolving parts of the chromosome.”

Relationship building

The current 47-people pangenome is just a starting point, however. The HPRC’s ultimate goal is to produce high-quality, nearly error-free genomes from at least 350 individuals from diverse populations by mid-2024, a milestone that would make it possible to capture rare alleles that confer important adaptive traits. Tibetans, for example, have alleles related to oxygen use and UV light exposure that enable them to live at high altitudes.

A major challenge in collecting this data will be to gain trust from communities that have seen past abuses of biological data; for example, there are no samples in the current study from Native American nor Aboriginal peoples, who have been long been disregarded or exploited by scientific studies. But you don’t have to go far back in time to find examples of unethical use of genetic data: Just a few years ago, DNA samples from thousands of Africans in multiple countries were commercialized without the donors’ knowledge, consent, or benefit.

These offenses have sown mistrust against scientists among many populations. But by not being included, some of these groups could remain genetically obscure, leading to a perpetuation of the biases in the data—and to continued disparities in health outcomes.

“It’s a complex situation that's going to require a lot of relationship building,” Jarvis says. “There's greater sensitivity now.”

And even today, many groups are willing to participate. “There are individuals, institutions, and governmental bodies from different countries who are saying, ‘We want to be part of this. We want our population to be represented,’” Jarvis says. “We’re already making progress.”

END

The clearest snapshot of human genomic diversity ever taken

2023-05-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers measure the light emitted by a sub-Neptune planet’s atmosphere for the first time

2023-05-10

For more than a decade, astronomers have been trying to get a closer look at GJ 1214b, an exoplanet 40 light-years away from Earth. Their biggest obstacle is a thick layer of haze that blankets the planet, shielding it from the probing eyes of space telescopes and stymying efforts to study its atmosphere.

NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) solved that issue. The telescope’s infrared technology allows it to see planetary objects and features that were previously obscured ...

Paper refutes assertion that effects of bottom trawling on blue carbon can be compared to that of global air travel

2023-05-10

A ‘Matter Arising’ paper published in Nature today refutes the findings of a paper by Sala et al on the amount of CO2 released from the seabed by bottom trawling. The paper made significant headlines around the world on release in 2021, as it equated the carbon released by bottom trawling to be of a similar magnitude to the CO2 created by the global airline industry.

In their paper quantifying the carbon benefits of ending bottom trawling, Prof Jan Hiddink of Bangor University’s world-renowned School of Ocean Science and others, explain that the methodology ...

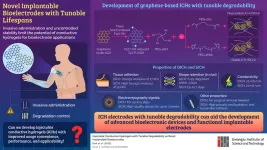

Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology researchers develop injectable bioelectrodes with tunable lifetimes

2023-05-10

Implantable bioelectrodes are electronic devices that can monitor or stimulate biological activity by transmitting signals to and from living biological systems. Such devices can be fabricated using various materials and techniques. But, because of their intimate contact and interactions with living tissues, selection of the right material for performance and biocompatibility is crucial. In recent times, conductible hydrogels have attracted great attention as bioelectrode materials owing to their flexibility, compatibility, and excellent interaction ability. However, the absence ...

Study of cancer metastasis, most common cause of cancer death, gets $35 million boost at Johns Hopkins Medicine

2023-05-10

FOR IMMMEDIATE RELEASE

With a $35 million gift from researcher, philanthropist and race car driver Theodore Giovanis, scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine will study the biological roots of the most fatal aspect of cancer: how it metastasizes, or spreads, through the body.

The contribution, a 15-year commitment, will establish the Giovanis Institute for Translational Cell Biology, dedicated to studying metastasis. The institute’s researchers aim to make discoveries that reveal common features of metastasis across cancer types, ...

Pandemic stress reshapes the placentas of expectant moms

2023-05-10

WASHINGTON (May 10, 2023) – Elevated maternal stress during the COVID-19 pandemic changed the structure, texture and other qualities of the placenta in pregnant mothers – a critical connection between mothers and their unborn babies – according to new research from the Developing Brain Institute at Children’s National Hospital.

Published in Scientific Reports, the findings spotlight the underappreciated link between the mental health of pregnant mothers and the health of the placenta – a critical organ ...

Local Phoenix medical students invited to upcoming medical conference to learn about opportunities in interventional cardiology

2023-05-10

A newly piloted program from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI), the leading society representing interventional cardiology, hopes to increase access and encourage interest in interventional cardiology early in students' medical careers.

SCAI's Ready to Launch - Careers in Cardiology program is designed to introduce future physicians to the field of interventional cardiology through a half-day program where attendees will get the opportunity to have impactful conversations with nationally recognized interventional cardiologists, learning about training paths, barriers to care and solutions for the future, the importance of health ...

A jumping conclusion: Fossil insect ID’d as new genus, species of prodigious leaper, the froghopper

2023-05-10

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A fossil arthropod entombed in 100-million-year-old Burmese amber has been identified as a new genus and species of froghopper, known today as an insect with prodigious leaping ability in adulthood following a nymphal stage spent covered in a frothy fluid.

Oregon State University researcher George Poinar Jr., an international expert in using plant and animal life forms preserved in amber to learn about the biology and ecology of the distant past, and his co-author, Alex E. Brown, published ...

Allison Institute announces appointment of inaugural members

2023-05-10

HOUSTON ― The James P. Allison Institute at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center today announced the appointment of its first members, James P. Allison, Ph.D., Padmanee Sharma, M.D., Ph.D., Jennifer Wargo, M.D., Sangeeta Goswami, M.D., Ph.D., and Kenneth Hu, Ph.D. In addition, Garry Nolan, Ph.D., will join the Allison Institute as an adjunct member.

These members include pioneering researchers who have made notable contributions to science as well as rising stars on the path toward important breakthroughs. This group ...

St. Jude scientist M. Madan Babu elected to the Royal Society of London

2023-05-10

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientist Madan Babu Mohan, Ph.D., Center of Excellence in Data-Driven Discovery director and member of the Department of Structural Biology, has been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. The Royal Society is the oldest scientific academy in continuous existence.

Babu was selected to join the Royal Society for his pioneering data science-based strategies to reveal fundamental principles in biological systems. His scientific accomplishments include determining the molecular mechanisms governing G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, uncovering the roles of disordered protein regions in biology and disease, ...

Sleep-tracker study finds fatigued officers struggle with investigations

2023-05-10

AMES, IA — Like many first responders, law-enforcement investigators and detectives often struggle with sleep. Late-night shifts, stress, and the 24-hour nature of crime can throw off biological clocks and cut sleep cycles short. Along with the negative health implications, new research indicates officers who are fatigued have a harder time collecting information that could bring justice to victims.

Zlatan Križan, a sleep scientist and psychology professor at Iowa State University, led the study. He ...