(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON – Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center, in collaboration with George Washington University, leveraged their understanding of auditory speech processing in the brain to enable volunteers to perceive speech through the sense of touch. This may aid in the design of novel sensory substitution devices -- swapping sound for touch, for example -- for hearing-impaired people.

The findings appear in the Journal of Neuroscience on May 17, 2023.

“In the past few years, our understanding of how the brain processes information from different senses has expanded greatly as we are starting to understand how brain networks are connected across different sensory pathways, such as vision, hearing and touch,” says Maximilian Riesenhuber, PhD, professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Georgetown University Medical Center and senior author of the study.

“For instance, previous work has shown that Braille words can activate the visual brain areas of blind individuals. This suggests that input from the touch system activates their visual system. Similar connections exist in individuals without sensory impairments, such as those between the hearing and touch system. These connections offer the intriguing possibility that it might be possible to process speech through the sense of touch by coming up with a way to effectively couple information from the sense of touch into the auditory speech system.”

Given the possibility of connecting touch and hearing, the researchers’ challenge was to transform spoken words into patterns of vibration that would provide “natural” input to brain areas that process spoken words. They collaborated with Lynne Bernstein, PhD, Silvio Eberhardt, PhD, and Edward Auer, PhD, at George Washington University, who have a long track record of investigating vibrotactile speech and who developed a vibrotactile transducer that could be used inside a magnetic resonance scanner. To test their hypothesis, the research teams trained 20 volunteers to recognize 60 words generated by one of two auditory-to-vibration transformation processes. Volunteers’ brains were scanned before and after training to identify where the vibration-transformed speech was being recognized in the brain.

“Quite remarkably, we found that vibration-transformed speech could activate the brain’s auditory speech recognition system in the same way auditory speech does,” said lead author Srikanth Damera, MD, PhD, who performed the research at Georgetown but is currently a resident at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

The key variable in the experiment was the auditory-to-vibration-transformation process. In the first group of ten people, the words were transformed in a fluid manner aimed to resemble auditory speech, whereas in the second group, the transformation broke a word up into phonemes and produced distinct chunked patterns (i.e., like morse code). It was only in the first group that the vibratory stimuli were perceived like spoken words in the brain, with the vibratory words activating the auditory speech system after training.

“This finding is significant because it opens the door to the development of better sensory substitution devices which aim to replace lost sensory function,” says Riesenhuber. “Our ultimate goal is to connect novel senses to networks that the brain is using to normally process input so that sensory substitution appears effortless and is perceived as natural – ideally, with people not even realizing that they are perceiving speech through touch.”

###

In addition to Riesenhuber and Damera, additional collaborators at Georgetown University include Patrick S. Malone, Benson W. Stevens and Richard Klein.

A portion of the funding for this research was provided by Facebook. Further support was provided by a National Science Foundation grant BCS-1439338.

The authors report having no personal financial interests related to the study.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

As a top academic health and science center, Georgetown University Medical Center provides, in a synergistic fashion, excellence in education — training physicians, nurses, health administrators and other health professionals, as well as biomedical scientists — and cutting-edge interdisciplinary research collaboration, enhancing our basic science and translational biomedical research capacity in order to improve human health. Patient care, clinical research and education is conducted with our academic health system partner, MedStar Health. GUMC’s mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on social justice and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or “care of the whole person.” GUMC comprises the School of Medicine, the School of Nursing, School of Health, Biomedical Graduate Education, and Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. Designated by the Carnegie Foundation as a doctoral university with "very high research activity,” Georgetown is home to a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health, and a Comprehensive Cancer Center designation from the National Cancer Institute. Connect with GUMC on Facebook (Facebook.com/GUMCUpdate) and on Twitter (@gumedcenter).

END

DETROIT (May 17, 2023) – Researchers at Henry Ford Health — one of the nation’s leading integrated academic medical institutions — in collaboration with Ephemeral Tattoo, have conducted a study on the safety and efficacy of made-to-fade tattoos for medical markings.

Fifty to 60 percent of cancer patients receive radiation therapy during their course of treatment. Patients have traditionally been required to receive small, permanent tattoos on their skin to ensure therapy is delivered accurately to the same place each time while minimizing healthy tissue exposure to radiation. On the heels of this study, Ephemeral will offer its innovative made-to-fade ...

In testing the genetic material of current populations in Africa and comparing against existing fossil evidence of early Homo sapiens populations there, researchers have uncovered a new model of human evolution — overturning previous beliefs that a single African population gave rise to all humans. The new research was published today, May 17, in the journal Nature.

Although it is widely understood that Homo sapiens originated in Africa, uncertainty surrounds how branches of human evolution diverged and how people migrated ...

There is broad agreement that Homo sapiens originated in Africa. But there remain many uncertainties and competing theories about where, when, and how.

In a paper published today in Nature, an international research team led by McGill University and the University of California-Davis suggest that, based on contemporary genomic evidence from across the continent, there were humans living in different regions of Africa, migrating from one region to another and mixing with one another over a period of hundreds of thousands of years. This view runs counter to some of the dominant theories about human origins in ...

A retrospective study of temperatures in the province of Barcelona reveals that low temperatures increase the risk of going on a period of sick leave, due in particular to infectious and respiratory diseases. The study, carried out by researchers from Center for Research in Occupational Health (CISAL) and the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences at UPF (MELIS); the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), an institution supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation and CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), shows that the sectors of the population most affected are women, young people and ...

In a study tracking climate-induced changes in the distribution of animals and their effects on ecosystem functions, North Carolina State University researchers show that resident species can continue managing some important ecological processes despite the arrival of newcomers that are similar to them, but resident species’ role in ecosystem functioning changes when the newcomers are more different.

The findings could lead to predictive tools for understanding what might happen as climate change forces new species into communities, such as the movement of species from lower to higher latitudes or elevations.

“Species ...

Abu Dhabi, UAE: – A team of scientists led by researchers at the University of Montreal has recently discovered an Earth-sized exoplanet, a world beyond our solar system, that may be carpeted with volcanoes and potentially hospitable to life. Called LP 791-18 d, the planet could undergo volcanic outbursts as often as Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in our solar system. The team includes Mohamad Ali-Dib, a research scientist at the NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) Center for Astro, Particle, and Planetary Physics.

The planet was found and studied using data ...

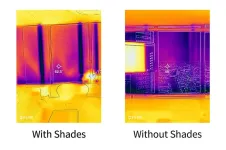

CHICAGO—May 17, 2023—Automated insulating window shades can cut energy consumption by approximately one-quarter and may recoup the cost of installation within three to five years, according to a landmark study conducted by Illinois Institute of Technology researchers at Willis Tower. The study, funded by ComEd, showcases a promising path for sustainability and energy efficiency in architectural design.

Temperature regulation typically accounts for 30–40 percent of the energy used by buildings in climates similar to Chicago. The research team, led by Assistant Professor of Architectural Engineering Mohammad ...

A large international team led by astronomers at the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at Université de Montréal (UdeM) today announced in the journal Nature the discovery of a new temperate world around a nearby small star.

This planet, named LP 791-18 d, has a radius and a mass consistent with those of Earth. Observations of this exoplanet and another one in the same system indicate that LP 791-18 d is likely covered with volcanoes similar to Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in our Solar System.

“The discovery of this exoplanet is an extraordinary ...

A pair of internationally renowned stem cell cloning experts at the University of Houston is reporting their findings of variant cells in the lungs of patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) which likely represent key targets in any future therapy for the condition.

IPF is a progressive, irreversible and fatal lung disease in which the lungs become scarred and breathing becomes difficult. The rapid development and fatal progression of the disease occur by uncertain mechanisms, but the most pervasive school of thought is that IPF arises from recurrent, subclinical lung ...

For more than a century, biologists have wondered what the earliest animals were like when they first arose in the ancient oceans over half a billion years ago.

Searching among today's most primitive-looking animals for the earliest branch of the animal tree of life, scientists gradually narrowed the possibilities down to two groups: sponges, which spend their entire adult lives in one spot, filtering food from seawater; and comb jellies, voracious predators that oar their way through the world's oceans in search of food.

In a new study published this week in the journal Nature, researchers use a novel approach based on chromosome structure to come up with ...