(Press-News.org) In the age of dinosaurs, many marine reptiles had extremely long necks compared to reptiles today. While it was clearly a successful evolutionary strategy, paleontologists have long suspected that their long-necked bodies made them vulnerable to predators. Now, after almost 200 years of continued research, direct fossil evidence confirms this scenario for the first time in the most graphic way imaginable.

Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 19 studied the unusual necks of two Triassic species of Tanystropheus, a type of reptile distantly related to crocodiles, birds, and dinosaurs. The species had unique necks composed of 13 extremely elongated vertebrae and strut-like ribs. Consequently, these marine reptiles likely possessed stiffened necks and waited to ambush their prey. But Tanystropheus’s predators apparently also took advantage of the long neck for their own gain.

Careful examination of their fossilized bones now shows that the necks of two existing specimens representing different species with severed necks have clear bite marks on them, in one case right where the neck was broken. The findings offer gruesome and exceedingly rare evidence for predator-prey interactions in the fossil record going back over 240 million years ago, the researchers say.

“Paleontologists speculated that these long necks formed an obvious weak spot for predation, as was already vividly depicted almost 200 years ago in a famous painting by Henry de la Beche from 1830,” said Stephan Spiekman of the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Germany. “Nevertheless, there was no evidence of decapitation—or any other sort of attack targeting the neck—known from the abundant fossil record of long-necked marine reptiles until our present study on these two specimens of Tanystropheus.”

Spiekman had studied these reptiles as the main subject of his doctoral work at the Paleontological Museum of the University of Zurich, Switzerland, where the specimens are housed. He recognized that two species of Tanystropheus lived in the same environment, one small species, about a meter and a half in length, likely feeding on soft-shelled animals like shrimp, and a much larger species of up to six meters long that fed on fish and squid. He also found clear evidence in the shape of the skull that Tanystropheus likely spent most of its time in the water.

It had been well known that two specimens of these species had well-preserved heads and necks that abruptly ended. It had been speculated that these necks were bitten off, but no one had studied this in detail. In the new study, Spiekman teamed up with Eudald Mujal, also of the Stuttgart Museum, and a research associate at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, Spain, who is an expert on fossil preservation and predatory interactions in the fossil record based on bite traces on bones. After an afternoon spent examining the two specimens in Zurich, they concluded that the necks had clearly been bitten off.

“Something that caught our attention is that the skull and portion of the neck preserved are undisturbed, only showing some disarticulation due to the typical decay of a carcass in a quiet environment,” Mujal said. “Only the neck and head are preserved; there is no evidence whatsoever of the rest of the animals. The necks end abruptly, indicating they were completely severed by another animal during a particularly violent event, as the presence of tooth traces evinces.”

“The fact that the head and neck are so undisturbed suggests that when they reached the place of their final burial, the bones were still covered by soft tissues like muscle and skin,” Mujal continued. “They were clearly not fed on by the predator. Although this is speculative, it would make sense that the predators were less interested in the skinny neck and small head, and instead focused on the much meatier parts of the body. Taken together, these factors make it most likely that both individuals were decapitated during the hunt and not scavenged, although scavenging can never be fully excluded in fossils that are this old.”

“Interestingly, the same scenario—although certainly executed by different predators—played out for both specimens, which remember, represent individuals of two different Tanystropheus species, which are very different in size and possibly lifestyle,” Spiekman says.

The findings confirm earlier interpretations that the ancient reptiles’ necks represent a completely unique evolutionary structure that was much narrower and stiffer than those of long-necked plesiosaurs, according to the researchers. They also show that evolving a long neck as a sea reptile came with potential downsides. Nevertheless, they note, elongated necks were clearly a highly successful evolutionary strategy, found in many different marine reptiles over a time span of 175 million years.

“In a very broad sense, our research once again shows that evolution is a game of trade-offs,” Spiekman says. “The advantage of having a long neck clearly outweighed the risk of being targeted by a predator for a very long time. Even Tanystropheus itself was quite successful in evolutionary terms, living for at least 10 million years and occurring in what is now Europe, the Middle East, China, North America, and possibly South America.”

####

This work was supported by the Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología - Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Current Biology, Spiekman et al. “Decapitation in the long-necked reptile Tanystropheus (Archosauromorpha, Tanystropheidae)” https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(23)00475-X

Current Biology (@CurrentBiology), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. Visit http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

END

Receptor patterns define key organisational principles in the brain, scientists have discovered.

An international team of researchers, studying macaque brains, have mapped out neurotransmitter receptors, revealing a potential role in distinguishing internal thoughts and emotions from those generated by external influences.

The comprehensive dataset has been made publicly available, serving as a bridge linking different scales of neuroscience - from the microscopic to the whole brain.

Lead author Sean Froudist-Walsh, ...

People who owned black-and-white television sets until the 1980s didn’t know what they were missing until they got a color TV. A similar switch could happen in the world of genomics as researchers at the Berlin Institute of Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB) have developed a technique called Genome Architecture Mapping (“GAM”) to peer into the genome and see it in glorious technicolor. GAM reveals information about the genome’s spatial architecture that is invisible to scientists using solely Hi-C, a workhorse tool developed in 2009 to study DNA interactions, reports a new study in Nature Methods by the Pombo lab.

“With ...

Scientists have long struggled to find the best way to present crucial facts about future sea level rise, but are getting better at communicating more clearly, according to an international group of climate scientists, including a leading Rutgers expert.

The consequences of improving communications are enormous, the scientists said, as civic leaders actively incorporate climate scientists’ risk assessments into major planning efforts to counter some of the effects of rising seas.

Writing in Nature Climate Change, the scientists ...

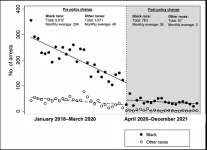

Ann Arbor, June 19, 2023 – De facto decriminalization of drug possession may be a good first step in addressing the disproportionate impact of an overburdened United States criminal justice system on the Black community. According to a new study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, published by Elsevier, this strategy was associated with significant and sustained reductions in low-level arrests. These arrests too often prevent drug users from obtaining needed treatments and services. The findings also suggest that while these policies may effectively reduce the overall arrest toll, striking disparities persist in how police are applying the directives across racial ...

Embargoed until 8am Eastern Time on Monday, June, 19, 2023

DALLAS, June 19, 2023 — Constant or chronic stress can affect overall well-being and may even impact heart health. Chronic stress can lead to increased blood pressure, heart rate and inflammation, which can contribute to developing chronic diseases.[1] The American Heart Association, the leading global voluntary health organization dedicated to fighting heart disease and stroke for all, today launches a new campaign to help the Hispanic/Latino community protect its overall well-being by addressing common stressors that ...

How do asset markets work? Which stocks behave similarly? Economists, physicists, and mathematicians work intensively to draw a picture but need to learn what is happening outside their discipline. A new paper now builds a bridge.

In a new study, researchers of the Complexity Science Hub highlight the connecting elements between traditional financial market research and econophysics. "We want to create an overview of the models that exist in financial economics and those that researchers in physics and mathematics have developed ...

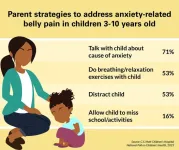

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Tummy aches are common among kids, with one in six parents in a new national poll saying their child experiences them at least once a month.

But not all parents seek professional advice when belly pain becomes a regular occurrence and just one in three are sure they’d know when it might be a sign of a serious problem, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health.

“Tummy complaints are common among children. This type of pain may be a symptom for a range of health issues, but it can be difficult to know if it’s ...

Undergraduates at UK universities experienced prolonged and high levels of psychological distress and anxiety during the pandemic, according to a new study, tracking wellbeing over the course of 2020 to 2021.

They also reported significantly lower levels of wellbeing, happiness and life satisfaction compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Published in the British Journal of Educational Studies, the University of Bolton research highlights how the stringent lockdown measures – including ...

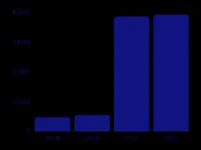

The power of transformative agreements (TAs) to drive the transition to open access (OA), especially in the Humanities and Social Sciences, is revealed in a new report published by Taylor & Francis. Accelerating open access in the UK explores in detail the first two years of Taylor & Francis’ OA partnership with the Jisc consortium and how it has boosted the global impact of research from UK institutions.

Supporting Humanities and Social Sciences researchers to publish OA

One of the report’s standout findings is the benefit of the TA for Humanities and Social Science ...

Houston, TX – New research by a team at Pennsylvania State University suggests that microbes in the human gut could be harnessed to block absorption of toxic metals like mercury and help the body absorb useful nutritional ones, like iron. The group presents their findings at ASM Microbe 2023, the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

Methylmercury, a neurotoxin, is particularly worrisome, said Daniela Betancurt-Anzola, a graduate student at Penn State who led the new study. It ...