"Greenland is off the charts when it comes to the proportion of people who are seeing and personally experiencing the effects of climate change. But there is a big mismatch between climate science and local awareness of human-caused climate change," said lead author Kelton Minor, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University's Data Science Institute and the Columbia Climate School. The researchers suggest that educational and cultural factors play a role.

Arctic regions are warming as much as four times faster than the world average, and Greenlanders, who rely on frigid seasonal conditions for hunting, fishing and travel, are on the front lines. Snow and sea ice, once predictable platforms for getting from place to place and making a living, are declining; rain storms are increasing, even in winter; permafrost is melting; and the mighty central ice sheet is rapidly losing mass. These changes are contributing to creeping sea-level rise on faraway shores, but for Greenlanders the effects are immediate.

The authors of the study surveyed some 1,600 people, some 4 percent of Greenland's adult population. They found that 89 percent believe climate change is happening—similar to other nations with at least some Arctic territory, including Sweden, Canada, Russia and Iceland. (The exception: the United States, at only 68 percent.) That said, the proportion of Greenlanders saying they are personally experiencing the effects is more than twice that of other Arctic nations—nearly 80 percent. Among fishers, hunters and people living in small, rural villages, the proportion is close to 85 percent.

Yet, when asked whether humans are causing the changes, only about 50 percent made this connection, and in rural areas it was only 40 percent.

The researchers say the study suggests that education plays a strong role, noting that many people in rural areas do not have a secondary education. "Villages don't have the same access to formal education, particularly past elementary school, and that may explain a lot of it," said Minor. He points out that climate researchers from around the world have been converging on Greenland for decades, and that much of the evidence pinning climate change on humans has emerged from their work. "One of the core insights of modern climate science, derived in part from the Greenland ice sheet, may not be widely available to Greenland's public," he said.

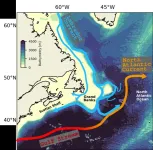

Warming climate works its way into nearly every aspect of life, in sometimes surprising ways. For instance, many people live on narrow strips of ice-free coastal land nestled up against the towering interior ice sheet. In some areas, the ice surface is melting so fast that it is perceptibly sinking, like the top of a mountain being bulldozed off; as a result, people in some settlements are getting more hours of daylight, as the sun rises over a newly lowered horizon. And, unlike most of the world, sea levels here are mostly sinking, not rising. This is due in part to the fact that as the ice wastes, pressure is taken off the land, and the land is rising. In a largely roadless land, this presents potential blockages to navigation in heavily used but already often shallow coastal waters—the subject of a separate investigation by Columbia scientists.

Cultural historian Manumina Lund-Jensen of Ilisimatusarfik Greenland University and a coauthor of the study suggests a further dimension to beliefs about humans and the environment. "In Greenland, most people interact with Sila, [the] Greenlandic spirit of the air, the weather, [which] also describes our consciousness, and connection to the universe," she said. "Knowledge about Sila has been transmitted through generations by oral traditions and observations, and can make the difference of survival for oneself and others." This view may "increase the psychological distance to the anthropogenic signal in the climate system," she writes in the study. "Humans may not be viewed as powerful in relation to Sila."

People's overall views of nature may have practical effects, the researchers say. Minor says that although it was not part of the current study, it seems that those who discount human influence may be more likely to view changes as mainly harmful—shorter hunting seasons, more dangerous storms, more unpredictable weather. On the other hand, those who make human the connection may see it differently. Case in point: the world is running short of sand, a key ingredient in concrete. Greenland is now swimming in it, as glaciers pull back, leaving behind vast deposits of it. Previous research indicates that those aware of human influence on climate are more likely to consider human action to adapt, said Minor, and favor exporting this suddenly available commodity.

"Perceptions of climate change impacts and causes are key drivers of societal climate mitigation and adaptation," said study coauthor Minik Rosing, a geologist at the University of Copenhagen. "Understanding how perceptions are shaped is fundamental for both climate change research and informing climate action."

The researchers write that policymakers and civic institutions should "support the convergence of highly adaptive Inuit knowledge of Sila and local climate variability with climate scientists' knowledge," and that climate projections and historical insights derived from the ice sheet "be widely disseminated and integrated into Greenland's primary school educational curricula in concert with Inuit knowledge."

A new survey shows that the largely Indigenous population of Greenland is highly aware that the climate is changing, and far more likely than people in other Arctic nations to say they are personally affected. Yet, many do not blame human influences—especially those living traditional subsistence lifestyles most directly hit by the impacts of rapidly wasting ice and radical changes in weather. The study appears this week in the journal Nature Climate Change.

"Greenland is off the charts when it comes to the proportion of people who are seeing and personally experiencing the effects of climate change. But there is a big mismatch between climate science and local awareness of human-caused climate change," said lead author Kelton Minor, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University's Data Science Institute and the Columbia Climate School. The researchers suggest that educational and cultural factors play a role.

Arctic regions are warming as much as four times faster than the world average, and Greenlanders, who rely on frigid seasonal conditions for hunting, fishing and travel, are on the front lines. Snow and sea ice, once predictable platforms for getting from place to place and making a living, are declining; rain storms are increasing, even in winter; permafrost is melting; and the mighty central ice sheet is rapidly losing mass. These changes are contributing to creeping sea-level rise on faraway shores, but for Greenlanders the effects are immediate.

The authors of the study surveyed some 1,600 people, some 4 percent of Greenland's adult population. They found that 89 percent believe climate change is happening—similar to other nations with at least some Arctic territory, including Sweden, Canada, Russia and Iceland. (The exception: the United States, at only 68 percent.) That said, the proportion of Greenlanders saying they are personally experiencing the effects is more than twice that of other Arctic nations—nearly 80 percent. Among fishers, hunters and people living in small, rural villages, the proportion is close to 85 percent.

Yet, when asked whether humans are causing the changes, only about 50 percent made this connection, and in rural areas it was only 40 percent.

The researchers say the study suggests that education plays a strong role, noting that many people in rural areas do not have a secondary education. "Villages don't have the same access to formal education, particularly past elementary school, and that may explain a lot of it," said Minor. He points out that climate researchers from around the world have been converging on Greenland for decades, and that much of the evidence pinning climate change on humans has emerged from their work. "One of the core insights of modern climate science, derived in part from the Greenland ice sheet, may not be widely available to Greenland's public," he said.

Warming climate works its way into nearly every aspect of life, in sometimes surprising ways. For instance, many people live on narrow strips of ice-free coastal land nestled up against the towering interior ice sheet. In some areas, the ice surface is melting so fast that it is perceptibly sinking, like the top of a mountain being bulldozed off; as a result, people in some settlements are getting more hours of daylight, as the sun rises over a newly lowered horizon. And, unlike most of the world, sea levels here are mostly sinking, not rising. This is due in part to the fact that as the ice wastes, pressure is taken off the land, and the land is rising. In a largely roadless land, this presents potential blockages to navigation in heavily used but already often shallow coastal waters—the subject of a separate investigation by Columbia scientists.

Cultural historian Manumina Lund-Jensen of Ilisimatusarfik Greenland University and a coauthor of the study suggests a further dimension to beliefs about humans and the environment. "In Greenland, most people interact with Sila, [the] Greenlandic spirit of the air, the weather, [which] also describes our consciousness, and connection to the universe," she said. "Knowledge about Sila has been transmitted through generations by oral traditions and observations, and can make the difference of survival for oneself and others." This view may "increase the psychological distance to the anthropogenic signal in the climate system," she writes in the study. "Humans may not be viewed as powerful in relation to Sila."

People's overall views of nature may have practical effects, the researchers say. Minor says that although it was not part of the current study, it seems that those who discount human influence may be more likely to view changes as mainly harmful—shorter hunting seasons, more dangerous storms, more unpredictable weather. On the other hand, those who make human the connection may see it differently. Case in point: the world is running short of sand, a key ingredient in concrete. Greenland is now swimming in it, as glaciers pull back, leaving behind vast deposits of it. Previous research indicates that those aware of human influence on climate are more likely to consider human action to adapt, said Minor, and favor exporting this suddenly available commodity.

"Perceptions of climate change impacts and causes are key drivers of societal climate mitigation and adaptation," said study coauthor Minik Rosing, a geologist at the University of Copenhagen. "Understanding how perceptions are shaped is fundamental for both climate change research and informing climate action."

The researchers write that policymakers and civic institutions should "support the convergence of highly adaptive Inuit knowledge of Sila and local climate variability with climate scientists' knowledge," and that climate projections and historical insights derived from the ice sheet "be widely disseminated and integrated into Greenland's primary school educational curricula in concert with Inuit knowledge."

# # #

Scientist contact: Kelton Minor km3876@columbia.edu

More information: Kevin Krajick, Senior editor, science news, Columbia Climate School kkrajick@climate.columbia.edu 917-361-7766

The Columbia Climate School develops innovative education, supports groundbreaking research and fosters essential solutions, from the community to the planetary scale.

Access our resources for journalists

END