(Press-News.org) A new study by researchers at the University of Cambridge reveals a surprising discovery that could transform the future of electrochemical devices. The findings offer new opportunities for the development of advanced materials and improved performance in fields such as energy storage, brain-like computing, and bioelectronics.

Electrochemical devices rely on the movement of charged particles, both ions and electrons, to function properly. However, understanding how these charged particles move together has presented a significant challenge, hindering progress in creating new materials for these devices.

In the rapidly evolving field of bioelectronics, soft conductive materials known as conjugated polymers are used for developing medical devices that can be used outside of traditional clinical settings. For example, this type of materials can be used to make wearable sensors that monitor patients’ health remotely or implantable devices that actively treat disease.

The greatest benefit of using conjugated polymer electrodes for this kind of devices is their ability to seamlessly couple ions, responsible for electrical signals in the brain and body, with electrons, the carriers of electrical signals in electronic devices. This synergy improves the connection between the brain and medical devices, effectively translating between these two types of signals.

In this latest study on conjugated polymer electrodes, published in Nature Materials, researchers report on an unexpected discovery. It is conventionally believed that the movement of ions is the slowest part of the charging process because they are heavier than electrons. However, the study revealed that in conjugated polymer electrodes, the movement of "holes" – empty spaces for electrons to move into - can be the limiting factor in how quickly the material charges up.

Using a specialised microscope, researchers closely observed the charging process in real-time, and found that when the level of charging is low, the movement of holes is inefficient, causing the charging process to slow down a lot more than anticipated. In other words, and contrary to standard knowledge, ions conduct faster than electrons in this particular material.

This unexpected finding provides a valuable insight into the factors influencing charging speed. Excitingly, the research team also determined that by manipulating the microscopic structure of the material, it is possible to regulate how quickly the holes move during charging. This newfound control and ability to fine tune the material’s structure could allow scientists to engineer conjugated polymers with improved performance, enabling faster and more efficient charging processes.

"Our findings challenge the conventional understanding of the charging process in electrochemical devices,” said first author Scott Keene, from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and the Electrical Engineering Division. “The movement of holes, which act as empty spaces for electrons to move into, can be surprisingly inefficient during low levels of charging, causing unexpected slowdowns."

The implications of these findings are far-reaching, offering a promising avenue for future research and development in the field of electrochemical devices for applications such as bioelectronics, energy storage, and brain-like computing.

"This work addresses a long-standing problem in organic electronics by illuminating the elementary steps that take place during electrochemical doping of conjugated polymers and highlighting the role of the band structure of the polymer", said George Malliaras, senior author of the study and Prince Philip Professor of Technology in the Department of Engineering’s Electrical Engineering Division.

“With a deeper understanding of the charging process, we can now explore new possibilities in the creation of cutting-edge medical devices that can seamlessly integrate with the human body, wearable technologies that provide real-time health monitoring, and new energy storage solutions with enhanced efficiency,” concluded Prof. Akshay Rao, co-senior author, also from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory.

The research was supported in part by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, the NVIDIA Academic Hardware Grant Program, Clare College, and the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. Scott Keene is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Cavendish Laboratory and the Department of Engineering’s Electrical Engineering Division.

END

New study shatters conventional wisdom and unlocks the future of electrochemical devices

2023-07-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study examines centuries of identity lost because of slavery

2023-07-06

Many Americans can trace some lines of their family tree back to the 1600s. However, African Americans descended from enslaved Africans, who began arriving in North America in 1619, lack ancestral information spanning several centuries.

A new USC and Stanford study, recently published in Genetics, provides insight into who occupies these missing branches of family trees — and gives a glimpse of how many branches there are.

“Slavery was not that many generations ago, so my family still tells stories about our enslaved ancestors, like who they were and, in my case, how we ended up as light as we are,” said first author Jazlyn Mooney, the Gabilan Assistant Professor of Quantitative ...

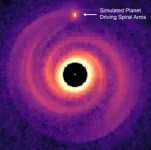

Astronomers discover elusive planet responsible for spiral arms around its star

2023-07-06

Depictions of the Milky Way show a coiling pattern of spiral "arms" filled with stars extending outward from the center. Similar patterns have been observed in the swirling clouds of gas and dust surrounding some young stars – planetary systems in the making. These so-called protoplanetary disks, which are the birthplaces of young planets, are of interest to scientists because they offer glimpses into what the solar system may have looked like in its infancy and into how planets may form in general. Scientists have long thought that spiral arms in these disks ...

New single-cell study provides novel insights into gastric cancer

2023-07-06

HOUSTON – A new study led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center provides a deeper understanding of the evolution of the tumor microenvironment during gastric cancer progression. Highlights of the study, published today in Cancer Cell, include a link between multicellular communities and clinical outcomes as well as a potential new therapeutic target.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is one of the most lethal cancers worldwide due to inherent treatment resistance, but the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the progression from early pre-cancer to tumor formation and metastasis are not well understood. This research sheds light on how the various ...

PLOS to extend accessible data to more articles and repositories

2023-07-06

SAN FRANCISCO — PLOS today is announcing that it has extended the scope of its “Accessible Data” experiment, which was first launched in March 2022, with support from a Wellcome Trust grant. The experimental “Accessible Data” feature is designed to increase research data sharing and reuse by highlighting links to select repositories with an eye-catching icon on the article page. We are now expanding from the original three repositories to nine, which together host about three quarters of the outputs linked to from PLOS articles.

PLOS began its Accessible Data experiment with two overarching goals. First, to increase reuse of datasets linked to PLOS articles ...

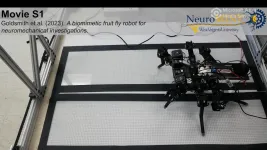

Big robot bugs reveal force-sensing secrets of insect locomotion

2023-07-06

Researchers have combined research with real and robotic insects to better understand how they sense forces in their limbs while walking, providing new insights into the biomechanics and neural dynamics of insects and informing new applications for large legged robots.

Campaniform sensilla (CS) are force receptors found in the limbs of insects that respond to stress and strain, providing important information for controlling locomotion. Similar force receptors exist in mammals known as Golgi tendon organs, suggesting that understanding the role ...

How dietary restraint could significantly reduce effects of genetic risk of obesity

2023-07-06

Obesity risk genes make people feel hungrier and lose control over their eating, but practicing dietary restraint could counteract this.

New research by University of Exeter, Exeter Clinical Research Facility, and University of Bristol – funded by the Medical Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership and published in the International Journal of Epidemiology - found that those with higher genetic risk of obesity can reduce the effects that are transmitted via hunger and uncontrolled eating by up to half through dietary restraint.

Psychology PhD student, Shahina Begum, from the University of Exeter is lead author and said: “At a time when high ...

Webb Telescope detects most distant active supermassive black hole

2023-07-06

Researchers have discovered the most distant active supermassive black hole to date with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The galaxy, CEERS 1019, existed about 570 million years after the big bang, and its black hole is less massive than any other yet identified in the early universe.

In addition to the black hole in CEERS 1019, the researchers identified two more black holes that are on the smaller side and existed 1 billion and 1.1 billion years after the big bang. JWST also identified eleven galaxies that existed when the universe was 470 million to 675 million years old. The evidence was provided ...

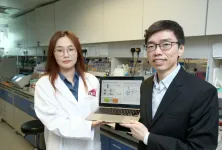

Unveiling the secret of viruses-bacteria interactions in man-made environments

2023-07-06

Viruses in man-made environments cause public health concerns, but they are generally less studied than bacteria. A recent study led by environmental scientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) provided the first evidence of frequent interactions between viruses and bacteria in man-made environments. It found that viruses can potentially help host bacteria adapt and survive in nutrient-depleted man-made environments through a unique gene insertion.

By understanding these virus–bacteria interactions and identifying the possible spread of antibiotic ...

ASBMB weighs in on changes to NIH fellowship review

2023-07-06

The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology sent feedback in June to the National Institutes of Health about its proposed changes to the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award fellowship application and review process.

The proposed changes indicate that the NIH adopted nearly all of the ASBMB’s earlier recommendations (here and here) to reduce institutional and investigator bias and refocus the evaluation on an applicant’s potential and the impact of the ...

Wastewater monitoring could act as pandemic early warning system

2023-07-06

Wastewater monitoring could act as an early warning system to help countries better prepare for future pandemics, according to a new study.

An international collaboration involving Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, The Rockefeller Foundation, Mathematica and the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency has shed light on how different countries monitor wastewater during infectious diseases outbreaks and where improvements could be made.

For the study, samples from treatment plants, rivers, wetlands and open drains were reported ...