(Press-News.org) BOSTON - A new multi-center study led by doctors at Boston Medical Center and Columbia University found that having a genetic variant in the prealbumin gene alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in older Black patients. Published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, researchers discovered that a blood test that measures the transthyretin or prealbumin protein might also be helpful in diagnosing transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy and could be used to trigger more definitive imaging testing.

Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR‐CM) is an underdiagnosed cause of congestive heart failure among patients 60+ years of age. There is a common genetic variant, V122I (or Val122Ile), in a protein called transthyretin (TTR) or prealbumin that is associated with ATTR-CM and present in 3.4% of Black individuals, or 1.5 million people. V122I is so common because when present, the variant is passed genetically from parent to child 50% of the time. Importantly, of those who have this variant, it is unknown who will develop ATTR.

Researchers note that since more people are getting their genes tested using commercial services, some of which return the V122I test result, it is important for people to know the association between a positive genetic result and the disease with which it is associated.

“Cardiac amyloidosis is a serious heart condition that can be caused by a common genetic variant carried by 1.5 million people,” said senior author Frederick L. Ruberg, MD, a cardiologist at Boston Medical Center and Associate Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine and Radiology at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. “Our study shows that of those who have inherited this variant, only 39% developed cardiac amyloidosis, so not everyone who inherits the variant will necessarily develop this serious condition.”

Researchers enrolled 278 self-identified Black heart failure patients from the Screening for Cardiac Amyloidosis with Nuclear Imaging in Minority Populations (SCAN-MP) study, funded by the National Institutes of Health. Study participants live in Boston and New York City and were tested for the genetic variant. Participants were also scanned with a special nuclear heart-imaging test to determine whether they have ATTR-CM.

With 1.5 million people carrying the V122I variant in the US, there are a great number people at risk for ATTR-CM. This study shows that though carriers may have the gene, they will not necessarily develop the disease. The study also shows that just testing for and identifying the V122I variant is not enough to infer that that heart failure is due to cardiac amyloidosis.

“Our study suggests that a widely available blood test to measure prealbumin levels may also be useful in identifying patients that should have more sensitive imaging testing for ATTR-CM,” said co-senior author Mathew Maurer, MD, Arnold and Arlene Goldstein Professor of Cardiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Director of the Cardiac Amyloidosi Program.. “Our results also help better understand how heart failure from ATTR-CM impacts older Black individuals.”

About Boston Medical Center

Boston Medical Center models a new kind of excellence in healthcare, where innovative and equitable care empowers all patients to thrive. We combine world-class clinicians, cutting-edge treatments, and advanced technology with compassionate, quality care, that extends beyond our walls. As an award-winning health equity leader, our diverse clinicians and staff interrogate racial disparities in care and partner with our community to dismantle systemic inequities. And as a national leader in research and the teaching affiliate for Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, we’re driving the future of care.

END

New study finds the prealbumin gene alone is insufficient for diagnosis of heart failure

2023-07-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A wearable ultrasound scanner could detect breast cancer earlier

2023-07-28

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- When breast cancer is diagnosed in the earliest stages, the survival rate is nearly 100 percent. However, for tumors detected in later stages, that rate drops to around 25 percent.

In hopes of improving the overall survival rate for breast cancer patients, MIT researchers have designed a wearable ultrasound device that could allow people to detect tumors when they are still in early stages. In particular, it could be valuable for patients at high risk of developing breast cancer in between ...

Mutation accessibility fuels influenza evolution

2023-07-28

(Memphis, Tenn.—July 28, 2023) The influenza (flu) virus is constantly undergoing a process of evolution and adaptation through acquiring new mutations. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital have added a new layer of understanding to explain why and how flu viruses change. The “survival of the accessible” model provides a complementary view to the more widely recognized “survival of the fittest” way of evolving. The work was published today in Science Advances.

Viruses undergo a rapid evolutionary flux due to constant genetic mutations. This rapid flux is why people get a flu shot ...

Billions in conservation spending fail to improve wild fish stocks in Columbia Basin

2023-07-28

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Four decades of conservation spending totaling more than $9 billion in inflation-adjusted tax dollars has failed to improve stocks of wild salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin, according to Oregon State University research.

The study led by William Jaeger of the OSU College of Agricultural Sciences is based on an analysis of 50 years of data suggesting that while hatchery-reared salmon numbers have increased, there is no evidence of a net increase in wild, naturally spawning salmon and steelhead.

Findings were published today in PLOS One.

Jaeger, a professor of applied economics, notes that ...

Imaging shows how solar-powered microbes turn CO2 into bioplastic

2023-07-28

ITHACA, N.Y. - When considering ways to sustainably generate environmentally friendly products, bacteria might not immediately spring to mind.

However, in recent years scientists have created microbe-semiconductor biohybrids that merge the biosynthetic power of living systems with the ability of semiconductors to harvest light. These microorganisms use solar energy to convert carbon dioxide into value-added chemical products, such as bioplastics and biofuels. But how that energy transport occurs in such a tiny, complex ...

Novel Raman technique breaks through 50 years of frustration

2023-07-28

Raman spectroscopy — a chemical analysis method that shines monochromatic light onto a sample and records the scattered light that emerges — has caused frustration among biomedical researchers for more than half a century. Due to the heat generated by the light, live proteins are nearly destroyed during the optical measurements, leading to diminishing and non-reproducible results. As of recently, however, those frustrations may now be a thing of the past.

A group of researchers with the Institute for Quantum Sciences and Engineering at Texas A&M ...

Unique Mexican black and pinto bean varieties are high in healthy compounds

2023-07-28

URBANA, Ill. – Common beans are important food sources with high nutritional content. Bean seeds also contain phenolic compounds, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that promote health. A study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and CIATEJ in Guadalajara, Mexico, explored the composition of seed coat extracts from black and pinto bean varieties unique to the Chiapas region of Southern Mexico.

“These beans are preserved among Mayan communities and grown by indigenous farmers. They are heirlooms from past generations and are important because of their cultural significance and contribution to biodiversity,” explained ...

Circadian clock gene helps mice form memories better during the day

2023-07-28

A gene that plays a key role in regulating how bodies change across the 24-hour day also influences memory formation, allowing mice to consolidate memories better during the day than at night. Researchers at Penn State tested the memory of mice during the day and at night, then identified genes whose activity fluctuated in a memory-related region of the brain in parallel with memory performance. Experiments showed that the gene, Period 1, which is known to be involved in the body’s circadian clock, is crucial for improved daytime memory performance.

The research demonstrates a link between the circadian system and memory formation ...

Neonatal stem cells from the heart could treat Crohn’s disease

2023-07-28

Research from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago found that direct injection of neonatal mesenchymal stem cells, derived from heart tissue discarded during surgery, reduces intestinal inflammation and promotes wound healing in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease-like ileitis, an illness marked by chronic intestinal inflammation and progressive tissue damage.

The study, published in the journal Advanced Therapeutics, offers a promising new and alternative treatment approach that avoids the pitfalls of current Crohn’s disease medications, including diminishing effectiveness, ...

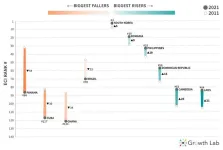

China, Indonesia, and Vietnam lead global growth for coming decade in new Harvard Growth Lab projections

2023-07-28

Cambridge, MA – China, India, Indonesia, Uganda, and Vietnam are projected to be among the fastest-growing economies for the coming decade, according to researchers at the Growth Lab at Harvard University. The new growth projections presented in The Atlas of Economic Complexity include the first detailed look at 2021 trade data, which reveal continued disruptions from the uneven economic recovery to the global pandemic. China is expected to be the fastest-growing economy per capita, although its growth rate is smaller than gains seen over the past decade.

Growth over the coming decade is projected to take off in three growth poles, East Asia, Eastern ...

Researchers tickle rats to identify part of the brain critical for laughter and playfulness

2023-07-28

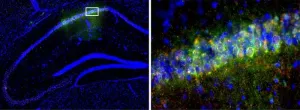

To study play behaviors in animals, scientists must be able to authentically simulate play-conducive environments in the laboratory. Animals like rats are less inclined to play if they are anxious or restrained, and there is minimal data on the brain activity of rats that are free to play. After getting rats comfortable with a human playmate, tickling them under controlled conditions, then measuring the rats’ squeaks and brain activity, a research team reports on July 27 in the journal Neuron that a structure in rat brains called the periaqueductal gray is essential for play and laughter.

“We know that vocalizations such as laughter are very ...