(Press-News.org) A gene that plays a key role in regulating how bodies change across the 24-hour day also influences memory formation, allowing mice to consolidate memories better during the day than at night. Researchers at Penn State tested the memory of mice during the day and at night, then identified genes whose activity fluctuated in a memory-related region of the brain in parallel with memory performance. Experiments showed that the gene, Period 1, which is known to be involved in the body’s circadian clock, is crucial for improved daytime memory performance.

The research demonstrates a link between the circadian system and memory formation and begins to piece together the molecular mechanisms that help form and keep memories. Understanding these mechanisms and the influence of time of day on memory formation could help researchers to determine how and when people learn best.

A paper describing the research appears online in journal Neuropsychopharmacology.

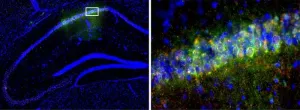

“The circadian system, which regulates physiological changes in our bodies across the 24-hour day, is shared across most organisms and is primarily controlled in a region of the brain called the superchiasmatic nucleus,” said Janine Kwapis, assistant professor of biology in the Eberly College of Science at Penn State and leader of the research team. “This system also influences day/night oscillations in other regions of the brain, including the dorsal hippocampus, one of the regions where memories are formed. Because memory formation is better during the day in many organisms, we were interested in understanding the molecular mechanisms that link the circadian clock to memory.”

The researchers tested the memory of the mice using an object memory location task that has been shown to specifically require the dorsal hippocampus. Essentially, the mice are exposed to two identical objects in specific locations. Later, the mice are again exposed to the objects, but one of them has been moved. If the mice then investigate the moved object more than the one that is still in its original location, it suggests that they remember the original configuration.

“Mice that were exposed to the memory location task during the day formed stronger long-term memories than mice exposed to the task at night,” said Lauren Bellfy, a graduate student in Kwapis’ lab and the first author of the paper. “We were then interested to know which stage of the memory formation process was being impacted by time of day.”

Long-term memory formation is often broken down into three phases. First, there is memory acquisition when the information is initially learned. Then the memory must be consolidated, during which molecular changes occur causing cellular and synaptic modifications in the brain that store the memory. Finally, to be useful, the memory must be retrieved at some later time.

The research team designed experiments that allowed them to show that memory acquisition and memory retrieval were not impacted by time of day, suggesting that memory consolidation was the main driver in the differences they saw in memory performance between day and night.

“Memory consolidation requires active molecular changes in neurons that result in synapse growth or remodeling,” said Kwapis. “These changes are driven by changes in gene activity or expression, so we isolated and sequenced all the genes being expressed in the dorsal hippocampus of mice that had been trained in the memory location task during the day or at night.”

Many genes fluctuate their activity across the day/night cycle independent of learning or memories, so the team compared the gene activity of the mice trained during the day and at night to these regular fluctuations. They found a dramatic increase in gene activity in the animals that were exposed to the memory task during the day, whereas the expression of many fewer genes were changed in the mice trained at night. One gene in particular that was expressed at high levels during the day but reduced at night was the clock gene, Period 1.

This gene was already known to play a crucial role in the circadian system in the superchiasmatic nucleus. What was exciting to the researchers was that this gene seems to function independently to regulate memory in the hippocampus, suggesting it ‘moonlights’ to regulate memory consolidation across the day/night cycle.

“Our lab had already been studying the role of the Period 1 gene in memory formation, but we didn’t know what role this gene was playing,” said Bellfy. “Here, we found evidence that Period 1 seems to regulate memory based on the time of day. When we shut down the activity of Period 1 in the dorsal hippocampus, we saw that these mice had impaired memory but most aspects of the circadian system still functioned normally.”

The team plan to continue investigating other genes whose activity was changed following learning.

“This work shows that Period 1 plays at least two important roles in the brain,” said Kwapis. “It was identified because of its role in regulating the circadian clock, but it appears to be equally important in memory formation. Understanding how memories form at this molecular level could help us to better understand memory-related disfunctions and potentially develop ways to address them. The connection between the circadian clock and memory formation could also be important for understanding how and when people learn best.”

In additions to Kwapis and Bellfy, the research team at Penn State includes graduate students Chad W. Smies, Aswathy Sebastian, and Hannah M. Boyd; undergraduate students Emily M. Stuart, Destiny S. Wright, Chen-Yu Lo, Alicia R. Bernhardt, and Megan J. von Abo; Kasuni K. Bodinayake, a research assistant in the Kwapis Lab; Shoko Murakami, a research scientist in the Kwapis Lab; and Istvan Albert, research professor of bioinformatics.

This research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Whitehall Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research, the Eberly College of Science and Department of Biology at Penn State, and the National Institute on Aging.

END

Circadian clock gene helps mice form memories better during the day

New research shows that the gene, Period 1, becomes more active in a memory-forming region of the brain in daylight hours after learning and plays a crucial role in consolidating memories

2023-07-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Neonatal stem cells from the heart could treat Crohn’s disease

2023-07-28

Research from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago found that direct injection of neonatal mesenchymal stem cells, derived from heart tissue discarded during surgery, reduces intestinal inflammation and promotes wound healing in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease-like ileitis, an illness marked by chronic intestinal inflammation and progressive tissue damage.

The study, published in the journal Advanced Therapeutics, offers a promising new and alternative treatment approach that avoids the pitfalls of current Crohn’s disease medications, including diminishing effectiveness, ...

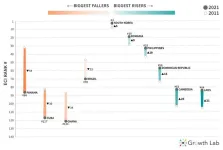

China, Indonesia, and Vietnam lead global growth for coming decade in new Harvard Growth Lab projections

2023-07-28

Cambridge, MA – China, India, Indonesia, Uganda, and Vietnam are projected to be among the fastest-growing economies for the coming decade, according to researchers at the Growth Lab at Harvard University. The new growth projections presented in The Atlas of Economic Complexity include the first detailed look at 2021 trade data, which reveal continued disruptions from the uneven economic recovery to the global pandemic. China is expected to be the fastest-growing economy per capita, although its growth rate is smaller than gains seen over the past decade.

Growth over the coming decade is projected to take off in three growth poles, East Asia, Eastern ...

Researchers tickle rats to identify part of the brain critical for laughter and playfulness

2023-07-28

To study play behaviors in animals, scientists must be able to authentically simulate play-conducive environments in the laboratory. Animals like rats are less inclined to play if they are anxious or restrained, and there is minimal data on the brain activity of rats that are free to play. After getting rats comfortable with a human playmate, tickling them under controlled conditions, then measuring the rats’ squeaks and brain activity, a research team reports on July 27 in the journal Neuron that a structure in rat brains called the periaqueductal gray is essential for play and laughter.

“We know that vocalizations such as laughter are very ...

Scientists discover secret of virgin birth, and switch on the ability in female flies

2023-07-28

Scientists have pinpointed a genetic cause for virgin birth for the first time, and once switched on the ability is passed down through generations of females.

For the first time, scientists have managed to induce virgin birth in an animal that usually reproduces sexually: the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Once induced in this fruit fly, this ability is passed on through the generations: the offspring can reproduce either sexually if there are males around, or by virgin birth if there aren’t.

For most animals, reproduction is sexual - it involves a female’s egg being fertilised by a male’s sperm. ...

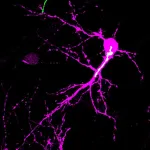

Uncovering how the Golgi apparatus impacts early postnatal neuron development

2023-07-28

Neurons are the cells that constitute neural circuits and use chemicals and electricity to receive and send messages that allow the body to do everything, including thinking, sensing, moving, and more. Neurons have a long fiber called an axon that sends information to the subsequent neurons. Information from axons is received by branch-like structures that fan out from the cell body, called dendrites.

Dendritic refinement is an important part of early postnatal brain development during which dendrites are tailored to make specific connections with appropriate axons. In a recently published paper, researchers present evidence showing how a mechanism within the neurons of a rodent involving ...

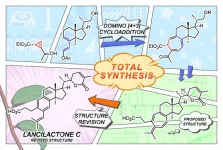

Total recall on HIV

2023-07-28

Kyoto, Japan -- Having control over how a dish is cooked is always a good idea. Taking a hint from the kitchen, scientists appear to have discovered a way to produce a true structure of the rare but naturally-occurring anti-HIV compound Lancilactone C from start to finish.

Its non-cytotoxicity in mammals could make this triterpenoid an ideal candidate for treating AIDS if its biological activity were clear -- and if only it were abundant in nature.

Now, a research group at Kyoto University has succeeded in ...

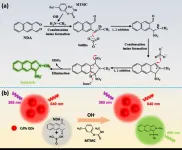

Scientists suggest AgNP/MoS2 nano-pocket for surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy scattering detection

2023-07-28

The research group of YANG Liangbao at the Institute of Health and Medical Technology, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS), Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) has recently developed a surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERMS) method to automatically capture target molecules in AgNP/MoS2 nano-pockets, which enables highly sensitive and long-duration dynamic detection of some chemical reaction processes.

The results were published in Analytical Chemistry and selected as the front cover.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a kind of molecular spectroscopy with fast, highly sensitive, ...

Solving the climate crisis requires collaboration between natural and social scientists

2023-07-28

Now that the world has experienced its hottest day in history, it is more urgent than ever for natural and social scientists to work together to address the climate crisis and keep global temperature increases below 2°C. To this end, an international group of esteemed researchers recently published an innovative research paper that highlights the importance of integrating knowledge from natural and social sciences to inform about effective climate change policies and practice. They argue that the concept of tipping points can serve as a bridge ...

A nanoprobe developed for visual quantitative detection of pesticides

2023-07-28

Recently, Prof. JIANG Changlong and his research team at the Institute of Solid State Physics, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science (HFIPS) of Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), developed and synthesized two highly effective ratiometric fluorescence nanoprobes. These nanoprobes, when combined with the color recognition capabilities of smartphones, enabled the visual and quantitative detection of pesticides in food and environmental water.

The research has been published in Chemical Engineering Journal and ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

Carbamate compounds ...

Retina cell breakthrough could help treat blindness

2023-07-28

Scientists have found a way to use nanotechnology to create a 3D ‘scaffold’ to grow cells from the retina –paving the way for potential new ways of treating a common cause of blindness.

Researchers, led by Professor Barbara Pierscionek from Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), have been working on a way to successfully grow retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells that stay healthy and viable for up to 150 days. RPE cells sit just outside the neural part of the retina and, when damaged, can cause vision to deteriorate.

It ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Father’s tobacco use may raise children’s diabetes risk

Structured exercise programs may help combat “chemo brain” according to new study in JNCCN

The ‘croak’ conundrum: Parasites complicate love signals in frogs

Global trends in the integration of traditional and modern medicine: challenges and opportunities

Medicinal plants with anti-entamoeba histolytica activity: phytochemistry, efficacy, and clinical potential

What a releaf: Tomatoes, carrots and lettuce store pharmaceutical byproducts in their leaves

Evaluating the effects of hypnotics for insomnia in obstructive sleep apnea

A new reagent makes living brains transparent for deeper, non-invasive imaging

Smaller insects more likely to escape fish mouths

Failed experiment by Cambridge scientists leads to surprise drug development breakthrough

Salad packs a healthy punch to meet a growing Vitamin B12 need

Capsule technology opens new window into individual cells

We are not alone: Our Sun escaped together with stellar “twins” from galaxy center

Scientists find new way of measuring activity of cell editors that fuel cancer

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

[Press-News.org] Circadian clock gene helps mice form memories better during the dayNew research shows that the gene, Period 1, becomes more active in a memory-forming region of the brain in daylight hours after learning and plays a crucial role in consolidating memories