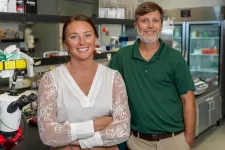

(Press-News.org) When Richard O’Neil, Ph.D., joined MUSC Hollings Cancer Center two years ago, he knew that he wanted to continue finding ways to make CAR-T-cell therapy easier on patients.

What he didn’t expect was that a side project – worked on by Megan Tennant, a graduate student in his lab, as a way to keep busy while a key piece of equipment was being serviced – would potentially open up this treatment beyond the world of cancer.

“I don't think that either of us expected that first initial experiment to work,” Tennant said. “But when we saw how well it worked and really started to conceptualize where this could go and how important this could be, it was exciting.”

O’Neil said they’ve begun conversations with biotechnology companies about how to push forward their findings.

“Right now, we're trying to out-license the technology,” O’Neil added. “The most interest, actually, has come in the context of lupus.”

CAR-T-cell therapy is currently used to treat some types of blood cancers that have returned after treatment or that haven’t responded to chemotherapy. It is both expensive and extensive – some of a patient’s T-cells are removed and sent to a lab where, in a process that can take several weeks, they’re engineered to add chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) that are tuned to home in on specific proteins on the surface of cancer cells. The newly formed CAR-T-cells are then reinfused into the patient to attack the cancer.

Some patients have experienced incredible recoveries after CAR-T-cell therapy. But they’ve also endured incredibly strong and scary side effects, in part because of the lymphodepleting chemotherapy that is performed before the CAR-T-cells are reinfused.

Lymphodepleting chemotherapy kills off existing T-cells to create a blank slate for the CAR-T-cells, and research has shown that the therapy is more effective after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

But O’Neil and Tennant, along with colleagues Christina New, M.D., and Leonardo Ferreira, Ph.D., believe that lymphodepleting chemotherapy isn’t necessary.

In a paper published in Molecular Therapy, they showed that encoding the CAR-T-cells with instructions to create a hyperactive form of protein STAT5 prompted the CAR-T-cells to engraft, or take root and begin multiplying, without requiring lymphodepletion. In their experiments, the engraftment process was cell autonomous, meaning it didn’t depend on the surrounding environment but happened solely because of the instructions from within the cells.

“We present a lot of evidence in the paper to support that notion that it's a completely cell autonomous process, and that it's fundamentally driven by activation of STAT5,” O’Neil said. “And so by transiently activating STAT5 during that phase of adoptive transfer, the initial engraftment phase, you're tricking the cells into essentially thinking they're going into a lymphodepleted environment.

“And so they engraft and become very functional, and they do everything they're supposed to do,” he continued. “Once we saw that they'd engraft, we just benchmarked how they functioned with as many different benchmarking assays as we could, comparing it to conventional adoptive transfer using lymphodepletion as our benchmark.”

O’Neil said they came to STAT5 because of its role in the cytokine signaling pathway. It’s been known for some time that the interleukin cytokines IL2, IL7 and IL15 are instrumental to the engraftment process. Some have suggested injecting patients with IL2 or IL15 in place of lymphodepleting chemotherapy, he said. But each of those cytokine pathways requires STAT5.

“We reasoned that we could recapitulate that entire signaling process at the node of STAT5, rather than trying to tickle it up at IL 15, or IL2 receptors. And by doing that, we also have more of a cell autonomous effect where we don't have to expose the patient to a bunch of IL7, IL15 and IL2, which can be dangerous,” O’Neil said.

The team used messenger RNA transfection to implant the instructions within the CAR-T-cells for activating STAT5.

In preclinical models, they found that their method reduced cytokine release syndrome, sometimes called cytokine storm, one of the most serious side effects. The CAR-T-cells carrying super STAT5 also got the cancer under control and appeared to create memory cells trained on that cancer.

O’Neil said that eliminating the need for lymphodepleting chemotherapy could mean that CAR-T-cell therapy would become viable for more types of diseases. The balance of harms and benefits of lymphodepleting chemotherapy is different for someone facing a recurrent lymphoma that no longer responds to chemotherapy than for someone with a chronic condition like lupus.

“You might be able to treat some of these more serious lupus cases,” O’Neil explained. “Doctors would never want to lymphodeplete somebody with lupus with the combined chemotherapies fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, but if we don’t have to lymphodeplete them anymore, then you can imagine trying out this therapy with them.”

Eliminating lymphodepletion could also change dosing schedules.

“Now you can imagine re-administrating dose after dose to the patient instead of ‘one and done.’ If you don't have to lymphodeplete them, you might be able to just give them an injection every month,” he said.

O’Neil is working with the MUSC lupus erythematosus research group on potentially developing clinical trials. He’s also talking to biotechnology companies that work in the CAR-T-cell realm and have the ability to launch new clinical trials.

He praised Tennant, in her last year of graduate school, for her diligence in pursuing the project.

“This has been Megan's labor of love,” he said. "It's actually been pretty remarkable. She just joined my lab when I came here two years ago, so this entire project came from conception to fruition in two years, which is pretty amazing and definitely shows what a talented and hard-working scientist Megan is.”

Acknowledgements

The researchers acknowledge the MUSC Translation Research Laboratory, a university-supported shared research resource supported by the Hollings Cancer Center Support grant (P30 CA138313), and grants IK2BX004585-01A1 (R.T.O.) and T32 DE01755 (M.D.T.). Schematics were created with BioRender.com.

About MUSC Hollings Cancer Center

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center is South Carolina’s only National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center with the largest academic-based cancer research program in the state. The cancer center comprises more than 130 faculty cancer scientists and 20 academic departments. It has an annual research funding portfolio of more than $44 million and sponsors more than 200 clinical trials across the state. Dedicated to preventing and reducing the cancer burden statewide, the Hollings Office of Community Outreach and Engagement works with community organizations to bring cancer education and prevention information to affected populations. Hollings offers state-of-the-art cancer screening, diagnostic capabilities, therapies and surgical techniques within its multidisciplinary clinics. Hollings specialists include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, psychologists and other clinical providers equipped to provide the full range of cancer care, including more than 200 clinical trials across South Carolina. For more information, visit hollingscancercenter.musc.edu.

END

CAR-T-cell therapy without side effects? Hollings researchers show results in preclinical models

2023-09-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The timing of fireworks-caused wildfire ignitions during the 4th of July holiday season

2023-09-07

Every year on the 4th of July, fireworks cause cause a precipitous increase of wildfire ignitions in the United States (U.S.). This human-environmental phenomenon is noteworthy and highlights the impact of American culture on wildfire activity in the U.S. In other regions of the world, research has increasingly shown that human culture impacts fire activity, with weekly cycles of fire activity reflecting the local structures of workweeks and the timing of religious days of rest (e.g., Saturdays and Sundays). Although 4th of July peak in wildfire igntions has ...

Dosage tweaks may hint at undiscovered interactions between medications

2023-09-07

Analysis of data from more than 1 million Danish inpatients identifies nearly 4,000 drug pairings that are associated with more frequent dosage adjustments when prescribed together—potentially hinting at previously undiscovered drug interactions. Søren Brunak of the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Digital Health.

In some cases, especially among elderly populations, a person may be prescribed several different medications at once in order to treat one or multiple health conditions—a phenomenon known as polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is associated with increased health risks due to the potential ...

How bright-light treatment improves sleep in stressed mice

2023-09-07

Chronic stress is associated with sleep disturbance. In their new study, Lu Huang and colleagues identify the neural pathway behind this behavior, and at the same time, explain how bright-light treatment is able to counter it. The research was conducted in mice at Jinan University in China and published September 7th in the open access journal PLOS Biology.

Bright-light treatment is known to improve sleep in those with sleep disorders, but how it works – and whether it works in cases of stress-induced sleep disturbances – was unknown. The researchers hypothesized that a part of the brain called the lateral habenula is deeply involved in this phenomenon because ...

Lack of evidence hampers progress on corporate-led ecosystem restoration

2023-09-07

A ‘near total’ lack of transparency is making it impossible to assess the quality of corporate-led ecosystem restoration projects, according to a Lancaster University-led study published today in Science.

Efforts to rebuild degraded environments are vital for achieving global biodiversity targets. The United Nations has launched a Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, and in recent years businesses around the world have collectively pledged to plant billions of trees, hundreds of thousands of corals and tens of ...

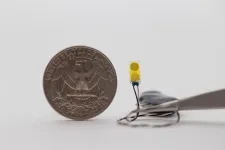

Implantable device enables earlier detection of kidney transplant failure in rats

2023-09-07

An implantable sensor provided advanced warning of kidney transplant failure in rats as much as several weeks earlier than commonly used biomarkers of kidney function, researchers report. The device, tested in a rat model of kidney transplantation, provides real-time continuous monitoring of organ temperature and thermal conductivity, detecting inflammatory processes associated with graft rejection. Although lifesaving for patients with end-stage kidney disease, long-term kidney transplantation survival remains a major challenge. Graft failure ...

2022 Hunga-Tonga eruption triggered fast and destructive submarine volcanic flows

2023-09-07

In 2022, the eruption of the submerged Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha apai volcano triggered a fast-moving and destructive underwater debris flow that severed telecommunication cables and reshaped the surrounding seafloor. The findings – representing some of the first fieldwork to document what happens when large volumes of erupted volcanic material are delivered directly into the ocean – provide new insights into the behavior and hazards of submerged volcanoes. Explosive volcanic eruptions on land create pyroclastic flows of hot ash and rock that, when they reach the ocean, can trigger damaging ...

Are large corporations upholding their conservation promises?

2023-09-07

Large transnational corporations (TNCs) are positioning themselves as environmental leaders, carrying out environmental restoration projects that go beyond their legal obligations. However, some corporations oversell their efforts. In this Policy Forum, Timothy Lamont and colleagues present an evaluation of sustainability reports of 100 of the world’s largest businesses, revealing the extent to which TNCs are claiming to contribute to, but failing to report on, ecosystem restoration. “Increased rigor, consistency, transparency, and accountability are needed to ensure that corporate-led restoration delivers quantifiable, ...

Nudging food delivery customers to skip the fork drastically cuts plastic waste, study shows

2023-09-07

In 2021, more than 400 million metric tons of plastic waste were produced worldwide, and it is predicted that the world’s plastic waste growth will continue to outpace the efforts to reduce plastic pollution in the coming decades. As food delivery services became increasingly popular during the COVID-19 pandemic, the surge in plastic waste generated by single-use cutlery has become a key environmental challenge for many countries. A new study finds “green nudges” that encouraged customers to skip asking for cutlery with their delivery orders were dramatically successful and could be a powerful policy tool to reduce plastic waste.

“Few policies target plastic waste ...

First device to monitor transplanted organs detects early signs of rejection

2023-09-07

A body can reject a transplanted organ at any time — even decades later

Signs of rejection must be caught early to intervene, preserve the organ

Current monitoring methods are intermittent, imperfect and sometimes invasive

New implant offers continuous monitoring by tracking the organ’s temperature

When temperatures change, an alert is sent to a smartphone or tablet in real time

EVANSTON, Ill. — Northwestern University researchers have developed the first electronic device for continuously monitoring ...

Fiber from crustaceans, insects, mushrooms promotes digestion

2023-09-07

Who can forget the stomach-churning moments when “Survivor” contestants forced down crunchy insects, among other unappetizing edibles, for a chance to win $1 million? In daring culinary challenges, the TV show’s contestants exhibited gastronomic bravery as viewers watched in discomfort.

Digesting a crunchy critter starts with the audible grinding of its rigid protective covering — the exoskeleton. Unpalatable as it may sound, the hard cover might be good for the metabolism, according to a new study, in mice, from Washington University School of Medicine ...