(Press-News.org) When two, three or four apples are placed in front of us, we are able to recognize the number of apples very quickly. However, we need significantly more time if there are five or more apples and we often also guess the wrong number. In fact, the brain does actually register smaller numbers of things differently than larger ones. This has been demonstrated in a recent study by the University of Tübingen, University of Bonn and the University Hospital Bonn. The results were published in the magazine Nature Human Behaviour.

Imagine that somebody shows us a photo of a string quartet and asks us to say how many people there are in the picture. There is not enough time to count them but we can all answer like a shot: “Four!” The next picture shows a septet and again we are only given enough time to take a quick look. We hesitate and are not quite so confident this time: “Eight.” The correct number is actually seven but we were very close.

There seems to be two distinctive ways in which we as humans tend to process numbers of things: We are usually able to detect small numbers of things very quickly and correctly. This is also described as “subitizing” in research circles. However, this method changes suddenly when there are five elements or more: We need more and more time to answer and our answers become increasingly imprecise.

Some researchers have thus speculated that there are two different processing methods in the brain – a precise one for small numbers and an estimation mechanism for larger numbers of things. “However, this idea has been disputed up to now,” explains Prof. Florian Mormann from the Department of Epileptology at the University Hospital Bonn, who carries out research at the University of Bonn. “It could also be that our brain always makes an estimate but the error rates for smaller numbers of things are so low that they simply go unnoticed.”

The neurons for smaller numbers of things are more selective

The recent study actually indicates, however, that we do indeed process small and large numbers of things differently. The research groups involved in the project were able to demonstrate some years ago that the brain has nerve cells responsible for each number. Some neurons fire, for example, primarily for two elements, other for four elements and again others for seven elements. “However, the neurons also fire in response to slight variations in the number,” explains Prof. Andreas Nieder from the University of Tübingen, who was the other main author of the study alongside Mormann. “A brain cell for a number of “seven” elements thus also fires for six and eight elements but more weakly. The same cell is still activated but even less so for five or nine elements.”

Nieder has already been able to demonstrate this “numerical distance effect” in experiments on monkeys. Interestingly, this effect only appears to occur in humans at higher numbers. “There seems to be an additional mechanism for numbers of around less than five elements that makes these neurons more precise,” says the neurobiologist.

When a brain cell for a number of three things fires, it simultaneously inhibits the brain cells for the numbers two and four. This reduces the risk that these cells will also incorrectly fire for the number three. However, this mechanism does not exist for the neurons activated for numbers five, six or eight. This is why there is a higher error rate for these numbers.

Observing individual brain cells at work

A special feature of the University Hospital Bonn benefited the researchers in their study: The Department of Epileptology at the hospital specializes in brain surgery. The doctors there try to treat epilepsy by carrying out operations to remove the diseased nerve tissue. In order to identify the location of the epileptogenic focus, they sometimes first insert electrodes into the affected person’s brain.

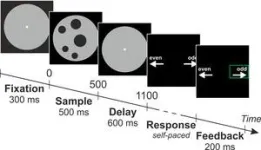

Seventeen patients participated in the latest study. In preparation for their operations, microelectrodes as fine as a human hair were inserted into the temporal lobe. “We were able to use them to measure the reaction of individual nerve cells to visual stimuli,” explains Esther Kutter, who carried out a large proportion of the experiments for her doctorate in the research group headed by Prof. Mormann.

The test subjects were seated in front of a computer screen on which different numbers of dots appeared for half a second. The participants were then asked to state whether they had seen an even or odd number of dots. They were able to respond very quickly and made practically no mistakes up to a number of four dots. After that, the number of errors increased with the number of dots, as did the amount of thinking time that the participants needed to complete their task.

This work will open up new insights into how numbers are processed in the human brain. In the long term, the findings could lead to a better understanding of dyscalculia, a developmental disorder associated with a poor understanding of numbers.

Participating institutes and funding:

The University of Tübingen, the University of Bonn and the University Hospital Bonn participated in the study. The research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) and the iBehave Research Network in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Publication: Esther F. Kutter, Gert Dehnen, Valeri Borger, Rainer Surges, Florian Mormann, Andreas Nieder: Distinct neuronal representation of small and large numbers in the human medial temporal lobe; Nature Human Behaviour; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01709-3

Media contact:

Prof. Dr. Dr. Florian Mormann

Department of Epileptology

University Hospital Bonn and University of Bonn

Tel. +49 (0)228/28715738

E-mail: florian.mormann@ukbonn.de

Prof. Dr. Andreas Nieder

Institute for Neurobiology, University of Tübingen

Tel. +49 (0)7071 29-75347

E-mail: andreas.nieder@uni-tuebingen.de

END

Nerve cells can detect small numbers of things better than large numbers of things

A study carried out in Tübingen and Bonn finds evidence of two separate processing mechanisms

2023-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Boston Children’s Hospital researchers uncover insights into the developmental trajectory of autism

2023-10-02

In a groundbreaking study published in JAMA Pediatrics on October 2, 2023, researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital shed new light on the evolving nature of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnoses in early childhood. Diagnosing ASD at a young age is important for early intervention and treatment, but this new study suggests that not all kids continue to meet the criteria for ASD as they get older.

The team found that 37% of children diagnosed with ASD as toddlers no longer meet the criteria for ASD around the age of six. Children with lower adaptive skills—essential everyday abilities encompassing communication, self-care, and decision-making—tend ...

Sustainable protection of rapidly subsiding coastlines with mangroves

2023-10-02

Vulnerable coastlines

Unfortunately, precisely in these rural densely populated Asian regions, mangroves have in the past been cleared to free up land for other uses such as aquaculture. This has made these coasts vulnerable to rapid erosion. Restoring mangroves seems a logical solution to reverse this process and protect these densely populated coastlines. However, this requires understanding if mangroves can cope with extreme rates of relative sea level rises, as experienced in these subsiding areas.

Since 2015 NIOZ researcher Celine van Bijsterveldt visited Indonesia regularly during her studies and her Phd. ...

Boreal and temperate forests now main global carbon sinks

2023-10-02

Using a new analysis method for satellite images, an international research team, coordinated by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) and INRAE, mapped for the first time annual changes in global forest biomass between 2010 and 2019. Researchers discovered that boreal and temperate forests have become the main global carbon sinks. Tropical forests, which are older and degraded by deforestation, fire and drought, are nearly carbon neutral. The findings, published in Nature Geoscience, highlight the importance of accounting for young forests and forest ...

Differences in mortality rates for fatal cerebral haemorrhage between Finnish university hospitals

2023-10-02

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is one of the most dangerous cerebrovascular disorders, with as many as 40% of patients dying within one month of the event.

A study recently published in the esteemed Neurology journal investigated whether there are differences in the prognosis of SAH patients between the university hospital districts in Finland. The research dataset was composed of nearly 10,000 SAH cases from 1998 to 2017, including information on patients who died before receiving neurosurgical care.

Prognoses ...

Smooth avatar-user synchronization for the metaverse

2023-10-02

Mobile phones, smartwatches and earbuds are some gadgets that we carry around physically without much thought. The increasingly digitalised world sees a shrinking gap between human and technology, and many researchers and companies are interested in how technology can be further integrated into our lives.

What if, instead of incorporating technology into our physical world, we assimilate ourselves into a virtual environment? This is what Assistant Professor Xiong Zehui from the Singapore University of Technology ...

Defense against the enemy within

2023-10-02

The research teams of Professor René Ketting at the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB) in Mainz, Germany, and Dr. Sebastian Falk at the Max Perutz Labs in Vienna, Austria, have identified a new enzyme called PUCH, which plays a key role in preventing the spread of parasitic DNA in our genomes. These findings may reveal new insights into how our bodies detect and fight bacteria and viruses to prevent infections.

Our cells are under constant attack from millions of foreign intruders, such as viruses and bacteria. To keep us from getting sick, ...

New tool reveals how drugs affect men, women differently -- and will make for safer medications

2023-10-02

UVA Health researchers have developed a powerful new tool to understand how medications affect men and women differently, and that will help lead to safer, more effective drugs in the future.

Women are known to suffer a disproportionate number of liver problems from medications. At the same time, they are typically underrepresented in drug testing. To address this, the UVA scientists have developed sophisticated computer simulations of male and female livers and used them to reveal sex-specific differences in how the tissues are affected by drugs.

The new model has already provided ...

Researchers develop mixture of compounds to help preserve organs before transplantation

2023-10-02

Using zebrafish as a model, investigators have determined a suitable combination of chemical compounds in which to store hearts, and potentially other organs, when frozen for extended periods of time before transplantation.

The work, which is published in The FASEB Journal, involved a variety of methods, including assays at multiple developmental stages, techniques for loading and unloading agents, and the use of viability scores to quantify organ function.

These methods allowed scientists to perform the largest and most comprehensive screen of cryoprotectant agents to determine their toxicity and efficiency at preserving ...

A surprising way to disrupt sleep

2023-10-02

Osaka, Japan - Circadian rhythms, the internal biological clocks that regulate our daily activities, are essential for maintaining health and well-being. While the role of transcription in these rhythms is well-established, a new study sheds light on the critical importance of post-transcriptional processes. The research, titled “Circadian ribosome profiling reveals a role for the Period2 upstream open reading frame in sleep,” to be published in PNAS, redefines our understanding of how translation and post-transcriptional processes influence the body’s internal clock and its impact on sleep patterns.

Timing Is Everything: ...

To Eat or Not to Eat: Targeting autophagy to enhance memory immune responses

2023-10-02

Osaka, Japan – Memory B cells depend on autophagy for their survival, but the protein Rubicon is thought to hinder this process. Researchers from Osaka University have discovered a shorter isoform of Rubicon called RUBCN100, which enhances autophagy in B cells. Mice that lacked the longer isoform, RUBCN130, produced more memory B cells in a way that relied on autophagy. These findings provide further insight into the role of Rubicon in autophagy.

Autophagy is a mechanism that degrades and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Increasing the number of coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction does not appear to reduce death rates

Tackling uplift resistance in tall infrastructures sustainably

Novel wireless origami-inspired smart cushioning device for safer logistics

Hidden genetic mismatch, which triples the risk of a life-threatening immune attack after cord blood transplantation

Physical function is a crucial predictor of survival after heart failure

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

[Press-News.org] Nerve cells can detect small numbers of things better than large numbers of thingsA study carried out in Tübingen and Bonn finds evidence of two separate processing mechanisms