(Press-News.org) Settling a half century of debate, researchers have discovered that tiny linear defects can propagate through a material faster than sound waves do.

These linear defects, or dislocations, are what give metals their strength and workability, but they can also make materials fail catastrophically – which is what happens every time you pop the pull tab on a can of soda.

The fact that they can travel so fast gives scientists a new appreciation of the unusual types of damage they might do to a broad range of materials in extreme conditions – from rock ripped apart by an earthquake rupture to aircraft shielding materials deformed by extreme stress, said Leora Dresselhaus-Marais, a professor at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University who co-led the study with Professor Norimasa Ozaki at Osaka University.

“Until now, no one has been able to directly measure how fast these dislocations spread through materials,” she said. Her team used X-ray radiography – similar to medical X-rays that reveal the inside of the body – to clock the speed of the propagating dislocations through diamond, yielding lessons that should apply to other materials, too. They described the results today in Science.

Chasing the speed of sound

Scientists have been debating whether dislocations can travel through materials faster than sound does for nearly 60 years. A number of studies concluded that they could not. But some computer models indicated that yes, they could – provided that they started out moving at faster-than-sound speed.

Getting them instantaneously up to this speed would require a tremendous shock. For one thing, sound travels a lot faster through solid materials than it does through air or water, depending on the nature and temperature of the material, among other factors. While the speed of sound through air is generally given as 761 mph, it’s 3,355 mph through water and an incredible 40,000 mph in diamond, the hardest material of all.

Complicating things even more, there are two types of sound waves in solids. Longitudinal waves are like the ones in air. But because solids put up some resistance to the passage of sound, they also host slower-moving waves known as transverse sound waves.

Knowing whether ultrafast dislocations can break either of these sound barriers is important from both the fundamental science and practical points of view. When dislocations move faster than sound speed, they behave quite differently and result in unexpected failures that have thus far only been modeled. Without measurements, no one knows how much damage those ultrafast dislocations can do.

“If a structural material fails more catastrophically than anyone expected because of its high rate of failure, that’s not so good,” said Kento Katagiri, a postdoctoral scholar in the research group and first author of the paper. “If it’s a fault rupturing through rock during an earthquake, for instance, it could cause more damage to everything. We need to learn more about this type of catastrophic failure.”

The results of this study, Dresselhaus-Marais added, “could suggest that what we thought we knew about the fastest possible materials failure was wrong.”

The pop-top effect

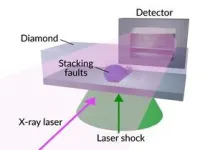

To get the first direct images of how fast dislocations can travel, Dresselhaus-Marais and her colleagues performed experiments at the SACLA X-ray free-electron laser in Japan. They did the experiments on tiny crystals of synthetic diamond.

Diamond offers a unique platform to study how crystalline materials fail, Katagiri said. For one thing, its deformation mechanism is simpler than those observed in metals, making it easier to interpret these challenging ultrafast X-ray imaging experiments.

“To understand the damage mechanisms, we need to identify features in our images that are unambiguously dislocations, and not other types of defects,” he said.

When two dislocations meet, they attract or repel each other and generate even more dislocations. Pop open a can of soda made from an aluminum alloy, and the many dislocations that are already in the lid – created when it was shaped into its final form – interact and spawn new dislocations by the trillions, which cascade into absolute critical failure as the top of the can flexes and the pop top snaps open. Those interactions and how they behave govern all the mechanical properties of materials we observe.

“In diamond, there are only four types of dislocation, while iron, for instance, has 144 different possible types of dislocations,” Dresselhaus-Marais said.

Diamond may be much harder than metal, the researchers said. But much like a soda can, it will still bend by forming billions of dislocations if it’s shocked hard enough.

Making X-ray images of shock waves

At SACLA, the team used intense laser light to generate shock waves in diamond crystals. Then they essentially took a series of ultrafast X-ray images of the dislocations forming and spreading on a timescale of billionths of a second. Only X-ray free-electron lasers can provide X-ray pulses short enough and bright enough to capture this process.

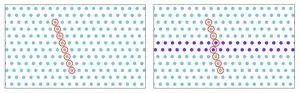

The initial shock wave split into two types of waves that continued to travel through the crystal. The first wave, called an elastic wave, temporarily deformed the crystal; its atoms bounced back into their original positions right away, like a rubber band that’s been stretched and released. The second wave, known as a plastic wave, permanently deformed the crystal by creating small errors in the repeating patterns of atoms that make up the crystal structure.

These tiny shifts, or dislocations, create “stacking faults” where adjacent layers of the crystal shift with respect to each other so they don’t line up the way they should. The stacking faults propagate outward from where the laser hit the diamond, and there is a moving dislocation at the leading tip of each stacking fault.

With X-rays, the researchers discovered that the dislocations spread through diamond faster than the speed of the slower type of sound waves, the transverse waves – a phenomenon that had never been seen in any material before.

Now, Katagiri said, the team plans to go back to an X-ray free-electron facility, such as SACLA or SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source, LCLS, to see if dislocations can travel faster than the higher, longitudinal speed of sound in diamond, which will require even more powerful laser shocks. If and when they break that sound barrier, he said, they will be considered truly supersonic.

Leora Dresselhaus-Marais is an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC and the Stanford PULSE Institute. Researchers from Osaka University, the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute, RIKEN SPring-8 Center and Nagoya University in Japan; DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Culham Science Center in the UK; and École Polytechnique in France also contributed to this research. Major funding came from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Citation: Kento Katagiri et al., Science, 6 October 2023 (10.1126/science.adh5563)

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

END

Groundbreaking study shows defects spreading through diamond faster than the speed of sound

Defects can make a material stronger or make it fail catastrophically; Knowing how fast they travel can help researchers understand things like earthquake ruptures, structural failures and precision manufacturing

2023-10-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI-driven earthquake forecasting shows promise in trials

2023-10-05

A new attempt to predict earthquakes with the aid of artificial intelligence has raised hopes that the technology could one day be used to limit earthquakes’ impact on lives and economies. Developed by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin, the AI algorithm correctly predicted 70% of earthquakes a week before they happened during a seven-month trial in China.

The AI was trained to detect statistical bumps in real-time seismic data that researchers had paired with previous earthquakes. The outcome was a weekly forecast in which the AI successfully predicted 14 earthquakes within about 200 miles of where it estimated they would happen and at almost exactly the ...

MSU research shows plants could worsen air pollution on a warming planet

2023-10-05

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Images

Highlights:

New Michigan State University research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that plants such as oak and poplar trees will emit more of a compound called isoprene as global temperatures climb.

Isoprene from plants represents the highest flux of hydrocarbons to the atmosphere behind methane.

Although isoprene isn’t inherently bad — it actually helps plants better tolerate insect pests and high temperatures — it can worsen air pollution by reacting ...

Barrow Neurological Institute receives $16.7 million NIH award to help coordinate new national ALS research consortium

2023-10-05

The purpose of the award is to create the Access for All in ALS (ALL ALS) Consortium to conduct clinical research that will include ALS patients nationwide, generating a longitudinal biorepository linked to detailed clinical information that will be made available to research scientists throughout the world using a web-based portal. As part of this new consortium Barrow will manage half of 34 clinical sites in the study which spans the U.S. and Puerto Rico. The consortium will be led by researchers at Barrow, Massachusetts General Hospital and Columbia University.

“Barrow Neurological Institute is honored to be selected by the NIH to help coordinate this ...

How to protect self-esteem when a career goal dies

2023-10-05

Many people fail at achieving their early career dreams. But a new study suggests that those failures don’t have to harm your self-esteem if you think about them in the right way.

Researchers found that people who viewed career goal failures as a steppingstone to new opportunities never lost self-esteem, no matter how many times they failed. But those who thought their failures left them worse off showed a drop-off in how they felt about themselves.

“It’s not how many times you have had to give up. It is how you felt about the failures, and whether you thought they led to something better for you,” ...

Ultrasensitive blood test detects ‘pan-cancer’ biomarker

2023-10-05

Pathology experts engineered an ultrasensitive test capable of detecting a highly specific biomarker found in multiple common cancers

In collaboration with cancer researchers across the country and the globe, the team evaluated the tool’s ability to detect the biomarker in ovarian cancer, gastroesophageal cancer, colon cancer, and other cancers

Diagnostic assays have potential for early cancer detection, monitoring, and prognostics

Marker ‘LINE-1 ORF1p’ is a protein encoded by a human transposon that has further potential applications in tissue diagnostics and may also facilitate treatment of cancers for which no accurate biomarkers ...

Insilico Medicine founder and CEO Alex Zhavoronkov, Ph.D., to present on AI drug discovery at LSX Nordic Congress

2023-10-05

Alex Zhavoronkov, Ph.D., founder and CEO of Insilico Medicine (“Insilico”) will present at the 6th LSX Nordic Conference happening in Copenhagen Oct. 10-11. Zhavoronkov, a leader in generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for drug discovery and biomarker development, will present on Oct. 11, 2pm CET on “‘How Artificial Intelligence is Shaping the Future of Drug Discovery, Design, and Development.”

The LSX Nordic Congress is a leading strategy, investment and partnering conference for the Nordic region connecting life science and healthcare ...

Grape consumption benefits eye health in human study of older adults

2023-10-05

In a recent randomized, controlled human study, consuming grapes for 16 weeks improved key markers of eye health in older adults. The study, published in the scientific journal Food & Function looked at the impact of regular consumption of grapes on macular pigment accumulation and other biomarkers of eye health.[1] This is the first human study on this subject, and the results reinforce earlier, preliminary studies where consuming grapes was found to protect retinal structure and function.[2]

Science has shown that an aging population has a higher risk of eye disease and vision problems. Key risk factors for eye disease include 1) oxidative ...

Don’t feel appreciated by your partner? Relationship interventions can help

2023-10-05

When we’re married or in a long-term romantic relationship, we may eventually come to take each other for granted and forget to show appreciation. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign finds that it doesn’t have to stay this way.

The study examined why perceived gratitude from a spouse or romantic partner changes over time, and whether it can be improved through relationship intervention programs.

“Gratitude almost seems to be a secret sauce to relationships, and an important piece to the puzzle of romantic relationships that hasn’t gotten much attention ...

Study confirms age of oldest fossil human footprints in North America

2023-10-05

The 2021 results began a global conversation that sparked public imagination and incited dissenting commentary throughout the scientific community as to the accuracy of the ages.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist ...

More than 10,000 pre-Columbian earthworks remain hidden throughout Amazonian forests

2023-10-05

More than 10,000 Pre-Columbian archaeological sites likely rest undiscovered throughout the Amazon basin, estimates a new study. The findings, derived from remote sensing data and predictive spatial modeling, address questions about the influence of pre-Columbian societies on the Amazon region. “The massive extent of archaeological sites and widespread human-modified forests across Amazonia is critically important for establishing an accurate understanding of interactions between human societies, Amazonian forests, and Earth’s climate,” write the authors. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

[Press-News.org] Groundbreaking study shows defects spreading through diamond faster than the speed of soundDefects can make a material stronger or make it fail catastrophically; Knowing how fast they travel can help researchers understand things like earthquake ruptures, structural failures and precision manufacturing