(Press-News.org) A microscopic discovery will not only enable scientists to understand the microbial world around us but could also provide a new way to control CRISPR-Cas biotechnologies.

An international team of researchers led by Professor Peter Fineran from the University of Otago and Dr Rafael Pinilla-Redondo from the University of Copenhagen has published a study in the prestigious journal Nature revealing new way viruses suppress the CRISPR-Cas immune systems of bacteria.

Co-first author Dr David Mayo-Muñoz, of the Phage-host interactions (Phi) laboratory in Otago’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology, says this finding could teach us about microbial dynamics in the environment, be used to make gene editing safer, and lead to more efficient alternatives to antibiotics.

“The discovery is exciting for the scientific community because it provides a greater understanding of how CRISPR-Cas defences can be stopped,” he says.

CRISPR-Cas are immune systems bacteria have that protect them from getting infected by bacterial viruses – called phages. It works by taking pieces of phage DNA and adding it to the bacterium’s genome. Bacteria end up with a memory bank of past phage infections which it files like mugshots, using them to identify and degrade that specific phage when it attacks again.

“If a virus comes in, part of its DNA is added to the memory bank, and then turned from DNA to RNA in the process. Each RNA acts like a guide so the CRISPR-Cas system can correctly identify and destroy the invading phage. Each addition to the memory bank is divided by a CRISPR repeat sequence, which stacks up like bookends between each phage sequence.

“The interesting thing is that phages have evolved different ways to overcome these defence systems – it’s like an evolutionary arms race. Bacteria have CRISPR-Cas so the phages have developed anti-CRISPRs, which enables them to block the immune complexes of the bacteria.

“What we’ve discovered is a whole new way that phages can stop CRISPR-Cas systems,” Dr Mayo-Muñoz says.

Previous researchers showed that some phages have CRISPR repeat sequences in their genomes and, in the current study, the Otago and Copenhagen team demonstrated that phages load bacteria with these RNA repeats to stop CRISPR–Cas.

Professor Fineran, head of the Phi laboratory at Otago, says these RNA anti-CRISPRs blind the immune complexes of the bacteria.

“Phages have components of bacterial CRISPR-Cas systems in their own genomes. They use these as molecular mimics for their own benefit to silence the immune system of bacteria and allow phage replication,” he says.

The group also found that when the phage loads RNA repeats onto the CRISPR-Cas proteins, not all of the right proteins load, forming a non-functional complex.

“This molecular mimic ruins the defences of the bacteria and the function of the system; it’s basically a decoy.”

A major interest in CRISPR-Cas lies in its programmable nature to precisely edit genomes – the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was recently awarded for this technology. Interestingly, anti-CRISPRs can be used as a safety switch to turn off or tune this technology.

“To harness the potential of CRISPR-Cas technologies, it is important to be able to control it, turn it on and off, and tune it, improving its accuracy and therapeutic benefit.

“Our discovery is the first evidence of an RNA anti-CRISPR, which has a shorter genetic sequence than previously discovered protein anti-CRISPRs, and since they are based on known CRISPR repeat sequences, we have the possibility to design RNA anti-CRISPRs for all CRISPR-Cas systems and their specific applications,” Dr Mayo-Muñoz says.

CRISPR-Cas will eventually be used for gene therapy – to repair mutated genes that cause disease – but to make it safer, anti-CRISPRs are needed to modulate the technology.

Phages can also be used as antimicrobials to kill pathogenic bacteria, offering an alternative to antibiotics, but if the infected bacterium has an active CRISPR-Cas system, phages with the right anti-CRISPRs will be needed to neutralise it.

“Being able to create a bespoke anti-CRISPR will be a powerful option to have in the toolbox.” Professor Fineran says.

“We are excited to be able to provide a whole new insight into how phages battle with their bacterial hosts. We hope that these RNA anti-CRISPRs will provide a new approach to help control CRISPR-Cas technologies.”

A microscopic discovery will not only enable scientists to understand the microbial world around us but could also provide a new way to control CRISPR-Cas biotechnologies.

An international team of researchers led by Professor Peter Fineran from the University of Otago and Dr Rafael Pinilla-Redondo from the University of Copenhagen has published a study in the prestigious journal Nature revealing new way viruses suppress the CRISPR-Cas immune systems of bacteria.

Co-first author Dr David Mayo-Muñoz, of the Phage-host interactions (Phi) laboratory in Otago’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology, says this finding could teach us about microbial dynamics in the environment, be used to make gene editing safer, and lead to more efficient alternatives to antibiotics.

“The discovery is exciting for the scientific community because it provides a greater understanding of how CRISPR-Cas defences can be stopped,” he says.

CRISPR-Cas are immune systems bacteria have that protect them from getting infected by bacterial viruses – called phages. It works by taking pieces of phage DNA and adding it to the bacterium’s genome. Bacteria end up with a memory bank of past phage infections which it files like mugshots, using them to identify and degrade that specific phage when it attacks again.

“If a virus comes in, part of its DNA is added to the memory bank, and then turned from DNA to RNA in the process. Each RNA acts like a guide so the CRISPR-Cas system can correctly identify and destroy the invading phage. Each addition to the memory bank is divided by a CRISPR repeat sequence, which stacks up like bookends between each phage sequence.

“The interesting thing is that phages have evolved different ways to overcome these defence systems – it’s like an evolutionary arms race. Bacteria have CRISPR-Cas so the phages have developed anti-CRISPRs, which enables them to block the immune complexes of the bacteria.

“What we’ve discovered is a whole new way that phages can stop CRISPR-Cas systems,” Dr Mayo-Muñoz says.

Previous researchers showed that some phages have CRISPR repeat sequences in their genomes and, in the current study, the Otago and Copenhagen team demonstrated that phages load bacteria with these RNA repeats to stop CRISPR–Cas.

Professor Fineran, head of the Phi laboratory at Otago, says these RNA anti-CRISPRs blind the immune complexes of the bacteria.

“Phages have components of bacterial CRISPR-Cas systems in their own genomes. They use these as molecular mimics for their own benefit to silence the immune system of bacteria and allow phage replication,” he says.

The group also found that when the phage loads RNA repeats onto the CRISPR-Cas proteins, not all of the right proteins load, forming a non-functional complex.

“This molecular mimic ruins the defences of the bacteria and the function of the system; it’s basically a decoy.”

A major interest in CRISPR-Cas lies in its programmable nature to precisely edit genomes – the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was recently awarded for this technology. Interestingly, anti-CRISPRs can be used as a safety switch to turn off or tune this technology.

“To harness the potential of CRISPR-Cas technologies, it is important to be able to control it, turn it on and off, and tune it, improving its accuracy and therapeutic benefit.

“Our discovery is the first evidence of an RNA anti-CRISPR, which has a shorter genetic sequence than previously discovered protein anti-CRISPRs, and since they are based on known CRISPR repeat sequences, we have the possibility to design RNA anti-CRISPRs for all CRISPR-Cas systems and their specific applications,” Dr Mayo-Muñoz says.

CRISPR-Cas will eventually be used for gene therapy – to repair mutated genes that cause disease – but to make it safer, anti-CRISPRs are needed to modulate the technology.

Phages can also be used as antimicrobials to kill pathogenic bacteria, offering an alternative to antibiotics, but if the infected bacterium has an active CRISPR-Cas system, phages with the right anti-CRISPRs will be needed to neutralise it.

“Being able to create a bespoke anti-CRISPR will be a powerful option to have in the toolbox.” Professor Fineran says.

“We are excited to be able to provide a whole new insight into how phages battle with their bacterial hosts. We hope that these RNA anti-CRISPRs will provide a new approach to help control CRISPR-Cas technologies.”

END

Scientists uncover new way viruses fight back against bacteria

2023-10-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Single vaccine protects against three deadly strains of coronavirus

2023-10-18

DURHAM, N.C. – A vaccine designed to protect against three different deadly coronaviruses shows success in mouse studies, demonstrating the viability of a pan-coronavirus vaccine developed by researchers at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute.

Publishing in the journal Cell Reports, the single nanoparticle vaccine included components of a previous vaccine that was shown to protect mice and primates against multiple variants of SARS-CoV-2, which is the virus that causes COVID-19. In this study, the vaccine protected mice from SARS-CoV-1, another form of SARS coronavirus that can infect humans, and a MERS coronavirus that has led to periodic, deadly outbreaks ...

Milestone: Miniature particle accelerator works

2023-10-18

Particle accelerators are crucial tools in a wide variety of areas in industry, research and the medical sector. The space these machines require ranges from a few square meters to large research centers. Using lasers to accelerate electrons within a photonic nanostructure constitutes a microscopic alternative with the potential of generating significantly lower costs and making devices considerably less bulky. Until now, no substantial energy gains were demonstrated. In other words, it has not been shown that electrons really have increased in speed significantly. A team of laser physicists at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg ...

Simple MRI scan could predict radiation side effects for prostate cancer

2023-10-18

A new Corewell Health study suggests that men who have longer prostatic urethras, the part of the urethra that travels through the prostate, may be at a higher risk of experiencing moderate, often chronic urinary side effects after receiving radiation for prostate cancer.

To date, researchers have struggled to determine any risk factors that could shed light on who might experience these types of side effects ahead of time. But now, a simple MRI scan and a new metric to determine urethra length could change that.

Results, now published in the journal Academic Radiology, indicate that for every 1-centimeter increase in length of the prostatic ...

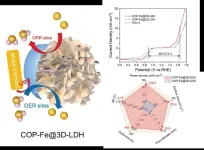

A newly hierarchically porous pyrolysis-free bifunctional catalyst to boost ultralong lifespan zinc-air batteries

2023-10-18

They published their work on Oct. 12 in Energy Material Advances.

"The development of cost-effective and high-performance zinc-air battery cathode catalyst is imperative," said paper author Zhonghua Xiang, professor with the Beijing University of Chemical Technology. "Currently, zinc-air batteries still not occupy the market, because they are limited in both stability and in their energy density."

Xiang explained that zinc-air batteries can only work for very limited time at high current density, because there are lots of problems of its cathode, anode and electrolyte.

"The air ...

Do adult periodical cicadas actually feed on anything?

2023-10-18

Annapolis, MD; October 18, 2023—Every so often, cicadas emerge above ground and blanket the earth with their exoskeletons while emitting a high-pitched chirp from sunrise to sunset. The periodical cicadas in the genus Magicicada come every 13 or 17 years, though other types of cicadas emerge much more frequently in our neighborhoods. A long-standing agricultural query related to the periodical cicadas was recently answered by an Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) research team at West Virginia's Appalachian Fruit Research Station. Simply: Once periodical ...

SwRI to host Life-Cycle Analysis for Transportation Symposium Nov. 16-17

2023-10-18

SAN ANTONIO — October 18, 2023 —Southwest Research Institute will host the Life-Cycle Analysis for Transportation Symposium on Nov. 16-17 in San Antonio. This year’s symposium will be in person for the first time.

The two-day event will highlight academic, industry and institutional research efforts to characterize the total greenhouse gas emissions produced during the entire life cycle of a vehicle, including its manufacture, service life and recycling or disposal.

“We often talk about getting to ‘zero-emissions,’ but this definition often ...

ASHG 2023 Annual Meeting to welcome thousands of researchers in Washington, DC to advance human genetics and genomics discoveries and applications

2023-10-18

Media Contact: Kara Flynn, 202.257.8424, press@ashg.org

For Immediate Release: Wednesday, October 18, 2023, 10:00am U.S. Eastern Time

ROCKVILLE, MD — More than ever before, human genetics and genomics is an essential part of making progress in research, biotechnology, and health. As a key leader supporting research innovation, the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) will convene more than 8,000 researchers and clinicians at the ASHG 2023 Annual Meeting in Washington DC, Nov. 1-5 to share emerging discoveries and celebrate the Society’s 75th anniversary.

“Human genetics is transforming science and health at a rapid ...

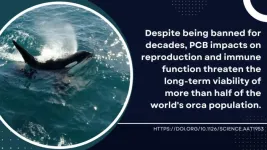

Map: Wildlife polluted by flame retardants on massive scale

2023-10-18

More than 150 species of wild animals across every continent are contaminated with flame retardant chemicals, according to a new map tracking peer-reviewed research worldwide. Polluted wildlife include killer whales, red pandas, chimpanzees and other endangered species. Added to furniture, electronics, vehicles, and other everyday products to meet flammability standards, the chemicals often do not work as intended. They also migrate out of products and into wildlife—and people.

“Flame retardants don’t actually make TV enclosures and car interiors more fire-safe, but they can harm people and animals,” ...

New insights into the genetics of the common octopus: genome at the chromosome level decoded

2023-10-18

Octopuses are fascinating animals – and serve as important model organisms in neuroscience, cognition research and developmental biology. To gain a deeper understanding of their biology and evolutionary history, validated data on the composition of their genome is needed, which has been lacking until now. Scientists from the University of Vienna together with an international research team have now been able to close this gap and, in a study, determined impressive figures: 2.8 billion base pairs - organized in ...

Researchers unveil fire-inhibiting nonflammable gel polymer electrolyte for lithium-ion batteries

2023-10-18

A collaborative research team, led by Professor Hyun-Kon Song in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST, Dr. Seo-Hyun Jung from Research Center for Advanced Specialty Chemicals at Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT), and Dr. Tae-Hee Kim from the Ulsan Advanced Energy Technology R&D Center at Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER), has achieved a groundbreaking milestone in battery technology. Their remarkable achievement in developing a non-flammable gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) is set to revolutionize the safety of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) by ...