(Press-News.org) Mosquitoes and other insects can carry human diseases such as dengue and Zika virus, but when those insects are infected with certain strains of the bacteria Wolbachia, this bacteria reduces levels of disease in their hosts. Humans currently take advantage of this to control harmful virus populations across the world.

New research led at UC Santa Cruz reveals how the bacteria strain Wolbachia pipientis also enhances the fertility of the insects it infects, an insight that could help scientists increase the populations of mosquitoes that do not carry human disease.

“With insect population replacement approaches, they keep all the mosquitos and just add Wolbachia so that fewer viruses are carried in those mosquitoes and transmitted to humans when they bite them — and it's working really, really well,” said Shelbi Russell, an assistant professor of biomolecular engineering at UCSC who led this research. “If there is some fertility benefit of Wolbachia that could evolve over time, then we could use that to select for higher rates of mosquitos that suppress our viral transmission.”

These results were detailed in a new paper led by Russell, published today in the journal PLOS Biology. UCSC Professor of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology William Sullivan is the paper’s senior author.

Humans and Wolbachia

Different strains of Wolbachia bacteria naturally infect a number of different animals worldwide, such as mosquitos, butterflies, and fruit flies. Once they infect an insect, the bacteria are able to manipulate the reproduction and development of their host to increase their own population. Humans take advantage of this to control the population size of insects that carry diseases that threaten us.

Wolbachia have developed a mechanism to poison the sperm of infected males so that if the male mates with an uninfected female, most of the potential offspring die at the very first cell division, and the rest are lost soon after. Humans have taken advantage of this to kill off insect populations.

However, research shows that later down the line once they have killed off as many uninfected hosts as possible, Wolbachia switch their evolutionary strategy to increase population levels of infected hosts. Understanding how this happens is important for avoiding unexpected consequences of human efforts to control insect populations.

“We need to understand all of these factors and their evolutionary potential if we're going to be releasing bacteria into new ecosystems,” Russell said. “They're evolving in real time, so we need to understand where these trajectories are going.”

Beyond disease prevention, controlling insect populations and range via bacteria could be an effective mechanism for crop security in the face of the changing climate.

Understanding increased fertility

The new results show that Wolbachia pipientis, which is native to fruit flies, has evolved to increase the fertility, and therefore the population size, of its fruit fly host. Previous research has found that the Wolbachia pipientis achieves this by manipulating a protein in fruit flies called Meiotic-P26 that affects fertility, but how exactly this happens was unclear.

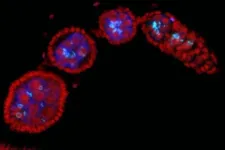

To investigate, Russell and her colleagues bred fruit flies with various defects affecting Mei-P26, which caused them to have reduced fertility. These defects occasionally occur naturally in the wild, but are hard to track in that setting. The researchers then examined what happened when they infected the flies with Wolbachia pipientis.

They found that Wolbachia infection restored the fruit fly’s fertility, enabling them to produce even more offspring than uninfected flies. The researchers found that Wolbachia can essentially undo gene defects in their host that would otherwise cause the population to go extinct. The Wolbachia rescue their host population through several strategies, including restoring fruit fly stem cells and ensuring that egg cells properly develop.

In further experiments, the researchers also found that, beyond rescuing fruit flies with defects, the Wolbachia pipientis infection also enhances the health and fertility of fruit flies without defects, resulting in higher egg lay and hatch rates for those insects.

Wolbachia in the lab

Russell focuses on Wolbachia because it and its fruit fly hosts are relatively easy to keep alive and reproduce in the lab. Oftentimes when scientists study bacteria, their efforts are hindered because either the host, the bacteria, or both are difficult to keep alive in the lab setting — even research into common bacteria important to humans such as Chlamydia are slowed by this problem. Wolbachia and their fruit fly hosts offer a rare opportunity to understand how bacteria can change the DNA and biological processes of their host.

“Through studying this system, I can learn a lot about how these weird bacteria work and how they integrate with host biology,” Russell said. “Bacteria are able to hop into these eukaryotes and leverage some of those mechanisms that their ancestors didn't even contain the genes for. It's a really fascinating thing in general, and it's cool that we can leverage this for biological control applications.”

Russell and her lab will continue to hone in on the specific changes that occur in the genomes and gene expression of host species, and look at the fertility benefits that Wolbachia may bring to their hosts in other insect populations.

Russell led this research primarily during her time as a postdoctoral scholar in Sullivan’s lab, where she was supported by the UC Santa Cruz Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship and funding from the National Institutes of Health.

END

Bacteria can enhance host insect’s fertility with implications for disease control

2023-10-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research Brief: U of M study suggests even more reasons to eat your fiber

2023-10-24

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (10/24/2023) — Health professionals have long praised the benefits of insoluble fiber for bowel regularity and overall health. New research from the University of Minnesota suggests even more reasons we should be prioritizing fiber in our regular diets. In a new study published in Nutrients, researchers found that each plant source of insoluble fiber contains unique bioactives — compounds that have been linked to lower incidence of cardiovascular disease, cancer and Type 2 diabetes — offering potential health benefits beyond ...

Raining cats and dogs: research finds global precipitation patterns a driver for animal diversity

2023-10-24

Since the HMS Beagle arrived in the Galapagos with Charles Darwin to meet a fateful family of finches, ecologists have struggled to understand a particularly perplexing question: Why is there a ridiculous abundance of species some places on earth and a scarcity in others? What factors, exactly, drive animal diversity?

With access to a mammoth set of global-scale climate data and a novel strategy, a team from the Department of Watershed Sciences in Quinney College of Natural Resources and the Ecology Center identified several factors to help ...

SDMPH welcomes Charles Parks Richardson, MD

2023-10-24

Charles Parks Richardson, MD, has been elected as a Board Member of the Society for Disaster Medicine and Public Health.

Dr. Richardson is an American physician who is both an accomplished physician and a medical innovator. He has not only been the inventor of several medical devices and pharmaceutical processes but has translated these into successful business ventures in partnership with such prestigious organizations as the American Heart Association.

He is currently the CEO of Critical Medical Infrastructure (CMI), KRS Global Biotechnology, and GeneRx, ...

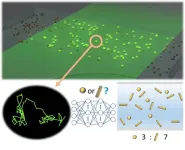

Deep learning solves long-standing challenges in identification of nanoparticle shape

2023-10-24

Innovation Center of NanoMedicine (iCONM; Center Director: Kazunori Kataoka; Location: Kawasaki, Japan) has announced with The University of Tokyo that a group led by Prof. Takanori Ichiki, Research Director of iCONM (Professor, Department of Materials Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo), proposed a new property evaluation method of nanoparticles’ shape anisotropy that solves long-standing issues in nanoparticle evaluation that date back to Einstein's time. The paper, titled " Analysis of Brownian motion trajectories of non-spherical nanoparticles ...

Large, real-world study compares modern treatment options for pulmonary embolism (REAL.PE)

2023-10-24

SAN FRANCISCO – A large, modern real-world analysis published today in the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (JSCAI), provides vital insights into the safety of novel therapies including ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis (USCDT) and mechanical thrombectomy (MT) that have been developed to address the increased morbidity and mortality of elevated risk pulmonary embolism (PE). Findings were presented today at TCT 2023.

Pulmonary embolism is a potentially life-threatening condition where a blood clot embolizes to the lungs, obstructing ...

NSF FABRIC project announces groundbreaking high-speed network infrastructure expansion

2023-10-24

The NSF-funded FABRIC project has completed installation of a unique network infrastructure connection, called the TeraCore—a ring spanning the continental U.S.—which boasts data transmission speeds of 1.2 Terabits per second (Tbps), or one trillion bits per second. FABRIC previously established preeminence with its cross-continental infrastructure, but the project has now hit another milestone as the only testbed capable of transmitting data at these speeds—the highest being twelve times faster than what was available ...

More animal welfare or more environmental protection?

2023-10-24

Which sustainability goals do people in Germany find more important: Animal welfare? Or environmental protection? Human health is another one of these competing sustainability goals. A team of researchers from the Department of Agricultural and Food Market Research at the University of Bonn have now found that consumers surveyed in their study would rather pay more for salami with an “antibiotic-free” label than for salami with an “open barn” label that indicates that the product promotes animal welfare. The results have now been published in the journal “Q Open.”

The animal husbandry sector ...

Mass General Brigham names Paul Anderson Chief Academic Officer

2023-10-24

Following a national search, Paul Anderson, MD, PhD, has been named Chief Academic Officer for Mass General Brigham. Anderson, who has been serving in this role on an interim basis since January 1, oversees Mass General Brigham’s world-class research and teaching enterprise, which includes two academic medical centers — Mass General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital — and three specialty hospitals. Mass General Brigham is the largest hospital system-based research enterprise in the nation, with an annual ...

Biological fingerprints in soil show where diamond-containing ore is buried

2023-10-24

Researchers have identified buried kimberlite, the rocky home of diamonds, by testing the DNA of microbes in the surface soil.

These ‘biological fingerprints’ can reveal what minerals are buried tens of metres below the earth’s surface without having to drill. The researchers believe it is the first use of modern DNA sequencing of microbial communities in the search for buried minerals.

The research published this week in Nature Communications Earth and Environment represents a new tool for mineral exploration, where a full toolbox could save prospectors time and a lot of money, says co-author Bianca Iulianella Phillips, a doctoral candidate at ...

Adding crushed rock to farmland pulls carbon out of the air

2023-10-24

Adding crushed volcanic rock to cropland could play a key role in removing carbon from the air. In a field study, scientists at the University of California, Davis, and Cornell University found the technology stored carbon in the soil even during an extreme drought in California. The study was published in the journal Environmental Research Communications.

Rain captures carbon dioxide from the air as it falls and reacts with volcanic rock to lock up carbon. The process, called rock weathering, can take millions of years ...