(Press-News.org) Zika virus infection in pregnant rhesus macaques slows fetal growth and affects how infants and mothers interact in the first month of life, according to a new study from researchers at the California National Primate Research Center at the University of California, Davis. The work, published Oct. 25 in Science Translational Medicine, has implications for both humans exposed to Zika virus and for other viruses that can cross the placenta, including SARS-CoV2, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Initially I thought this was a story about Zika, but as I looked at the results I think this is also a story about how fetal infections in general affect developmental trajectories,” said Eliza Bliss-Moreau, professor of psychology at UC Davis and senior author on the paper.

In most people, Zika virus infection causes mild or no symptoms and leaves long-lasting immunity. But during pregnancy, the virus can cross the placenta and cause damage to the nervous system of the fetus. In extreme cases, it can cause microcephaly in humans.

While no local transmission of the virus has been reported in the U.S. since 2018, the mosquitoes that carry Zika virus continue to expand their range throughout Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific.

UC Davis researchers previously showed that Zika virus could enter the fetal brain in pregnant macaques. The new study, led by Bliss-Moreau with Associate Specialist Gilda Moadab, Project Scientist Florent Pittet and colleagues at the CNPRC and UC Davis Department of Psychology, looked at the effects of Zika infection during the second trimester of pregnancy on infants up to a month after birth.

Infection in second trimester

Pregnant animals did not become visibly ill with the virus, but ultrasounds showed fetal growth slowed after infection, Pittet said. At birth, Zika-exposed infants were “at the low end” of the range for head size in rhesus macaques.

“They were smaller overall,” he said. Higher levels of circulating Zika virus corresponded with longer delays in growth.

After birth, the researchers tracked the development of sensory and motor skills – using tests similar to those used for human babies – and interaction with the mother.

“The trajectory was quite different,” Pittet said. Right after birth, infant monkeys spend a lot of time on their mother but start to separate after about two weeks. But the Zika infants spent much more time clinging to their mothers through the first month.

It’s not clear whether the mother or the infant is initiating this contact, Bliss-Moreau said.

“We know that moms will keep hold of infants that are having challenges,” she said.

Males more affected

Surprisingly, growth delays and effects on mother-infant interactions were greater in male than in female infants, although both showed delays compared to uninfected controls. Infectious disease studies in animals tend to use one sex (usually male) to avoid confounding effects, but potentially missing such sex differences.

Additionally, the animals were housed in established social groups of multiple adult females (including their mother), a single male and other male and female infants of about the same age. This allows the infants to learn from each other and from the adults, Pittet said.

“The presence of unrelated adults and infants in the social group is a critical factor for normative development,” he said. “Offering such a social rearing environment is tons of additional work but ensures a lot more relevance to developmental studies.”

Upcoming papers will describe the monkeys’ growth through the first two years of life. Zika virus exposure during pregnancy sets off a cascade of consequences that may not appear until later in development, Pittet said.

The finding that outcomes correlate with viral load during pregnancy offers opportunities to intervene, the researchers said. A drug or vaccine would not have to completely eliminate the virus to be beneficial. This may be generally true for other infections that can affect the fetus, such as COVID.

“Anything you can do to reduce viral load is a good thing for infant development,” Bliss-Moreau said. A 2019 study by CNPRC scientists, in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, found that an experimental Zika vaccine lowered levels of circulating viruses in pregnant macaques.

Additional coauthors are: Jeffrey Bennett, Christopher Taylor, Olivia Fiske and Koen van Rompay at the CNPRC; and Anil Singapuri and Lark Coffey, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

END

Zika infection in pregnant macaques slows fetal growth

2023-10-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Chloroplasts do more than photosynthesis: They’re also a key player in plant immunity

2023-10-25

Scientists have long known that chloroplasts help plants turn the sun’s energy into food, but a new study, led by plant biologists at the University of California, Davis, shows that they are also essential for plant immunity to viral and bacterial pathogens.

Chloroplasts are generally spherical, but a small percentage of them change their shape and send out tube-like projections called “stromules.” First observed over a century ago, the biological function of stromules has remained ...

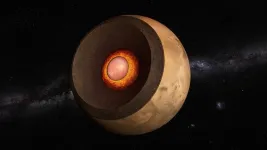

Mystery of the Martian core solved

2023-10-25

For four years, NASA’s InSight lander recorded tremors on Mars with its seismometer. Researchers at ETH Zurich collected and analysed the data transmitted to Earth to determine the planet’s internal structure. “Although the mission ended in December 2022, we’ve now discovered something very interesting,” says Amir Khan, a Senior Scientist in the Department of Earth Sciences at ETH Zurich.

An analysis of recorded marsquakes, combined with computer simulations, paint ...

Book examines history of standardized tests in American schools, why they persist

2023-10-25

LAWRENCE — For the past 50 years, standardized tests have been the norm in American schools, a method proponents say determines which schools are not performing and helps hold educators accountable. Yet for the past 20 years, it has become clear that testing has failed to improve education or hold many accountable, according to a University of Kansas researcher whose new book details its history.

“An Age of Accountability: How Standardized Testing Came to Dominate American Schools and Compromise Education” by John Rury, professor emeritus of educational leadership & policy studies at KU, tells the story of how testing became ...

On the trail of the silver king: Researchers at UMass Amherst reveal unprecedented look at tarpon migration

2023-10-25

October 25, 2023

On the Trail of the Silver King: Researchers at UMass Amherst Reveal Unprecedented Look at Tarpon Migration

Culmination of more than five-years’ research, $1.1 million in grants and collaborations with anglers, industry and Bonefish & Tarpon Trust promises to reshape conservation efforts

AMHERST, Mass. – New research led by the University of Massachusetts and published recently in Marine Biology unveils a first-of-its-kind dataset, gathered over five years, that gives the finest-grained ...

Stanford collaboration offers new method to analyze implications of large-scale flood adaptation

2023-10-25

During the summer of 2022, the Indus River in Pakistan overflowed its banks and swept through the homes of between 30-40 million people. Eight million were permanently displaced, and at least 1,700 people died. Damages to crops, infrastructure, industry, and livelihoods were estimated at $30 billion. In response to this, Stanford researchers from the Natural Capital Project (NatCap) and the Carnegie Institution for Science collaborated on a new way to quickly calculate the approximate depths of ...

Amid cocaine addiction, the brain struggles to evaluate which behaviors will be rewarding

2023-10-25

Rutgers researchers have used neuroimaging to demonstrate that cocaine addiction alters the brain’s system for evaluating how rewarding various outcomes associated with our decisions will feel. This dampens an error signal that guides learning and adaptive behavior.

The observed changes likely propagate a mysterious aspect of some addictive behavior—the tendency to keep doing harmful things that sometimes have no immediate benefit. Those changes also make it harder for long-term users of cocaine to correctly estimate how much benefit they’ll derive from other available actions.

Experts have long hypothesized that cocaine and other addictive ...

Study shows thyroid cancer is more common among transgender female veterans

2023-10-25

A new study by UC Davis Health endocrinology researchers has shown a high prevalence of thyroid cancer among transgender female veterans. It’s the first evidence of such a disparity in the transgender female population in the United States.

The researchers presented their findings this month at the American Thyroid Association Annual Meeting.

The study was prompted by what the doctors noticed while caring for patients.

“As a group of physicians, we observed anecdotally through clinical observation that among 50 transgender women in our clinic, two were diagnosed with thyroid ...

Study suggests marijuana use damages brain immune cells vital to adolescent development

2023-10-25

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

In a mouse study designed to explore the impact of marijuana’s major psychoactive compound, THC, on teenage brains, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say they found changes to the structure of microglia, which are specialized brain immune cells, that may worsen a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia. The findings, published Oct. 25 in Nature Communications, add to growing evidence of risk to brain development in adolescents who smoke or eat marijuana products.

“Recreational ...

NASA's Webb makes first detection of heavy element from star merger

2023-10-25

A team of scientists has used multiple space and ground-based telescopes, including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, to observe an exceptionally bright gamma-ray burst, GRB 230307A, and identify the neutron star merger that generated an explosion that created the burst. Webb also helped scientists detect the chemical element tellurium in the explosion’s aftermath.

Other elements near tellurium on the periodic table – like iodine, which is needed ...

A bold plan to 3D print artificial coral reef

2023-10-25

Inspired by the remarkable durability of ancient Roman construction materials in seawater, a University of Texas at Arlington civil engineering researcher is attempting to duplicate Roman concrete by developing 3D-printed materials to restore damaged or dying coral reefs.

Warda Ashraf, associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering, will lead a multidisciplinary team, funded by a $2 million National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, that aims to build 3D-printed artificial reefs. The team’s project is titled “Carbon Sequestration and Coastal Resilience Through 3D Printed Reefs” ...