(Press-News.org) No one had ever seen one virus latching onto another virus, until anomalous sequencing results sent a UMBC team down a rabbit hole leading to a first-of-its-kind discovery.

It’s known that some viruses, called satellites, depend not only on their host organism to complete their life cycle, but also on another virus, known as a “helper,” explains Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences. The satellite virus needs the helper either to build its capsid, a protective shell that encloses the virus’s genetic material, or to help it replicate its DNA. These viral relationships require the satellite and the helper to be in proximity to each other at least temporarily, but there were no known cases of a satellite actually attaching itself to a helper—until now.

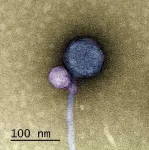

In a paper published in the Journal of the International Society of Microbial Ecology, a UMBC team and colleagues from Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) describe the first observation of a satellite bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacterial cells) consistently attaching to a helper bacteriophage at its “neck”—where the capsid joins the tail of the virus.

In detailed electron microscopy images taken by Tagide deCarvalho, assistant director of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Core Facilities and first author on the new paper, 80 percent (40 out of 50) helpers had a satellite bound at the neck. Some of those that did not had remnant satellite tendrils present at the neck. Erill, senior author on the paper, describes them as appearing like “bite marks.”

“When I saw it, I was like, I can’t believe this,” deCarvalho says. “No one has ever seen a bacteriophage—or any other virus—attach to another virus.”

A long-term virus relationship

After the initial observations, Elia Mascolo, a graduate student in Erill ‘s research group and co-first author on the paper, analyzed the genomes of the satellite, helper, and host, which revealed further clues about this never-before-seen viral relationship. Most satellite viruses contain a gene that allows them to integrate into the host cell’s genetic material after they enter the cell. This allows the satellite to reproduce whenever a helper happens to enter the cell from then on. The host cell also copies the satellite’s DNA along with its own when it divides.

A bacteriophage sample from WashU also contained a helper and a satellite. The WashU satellite has a gene for integration and does not directly attach to its helper, similar to previously observed satellite-helper systems.

However, the satellite in UMBC’s sample, named MiniFlayer by the students who isolated it, is the first known case of a satellite with no gene for integration. Because it can’t integrate into the host cell’s DNA, it must be near its helper—named MindFlayer—every time it enters a host cell if it is going to survive. Given that, although the team did not directly prove this explanation, “Attaching now made total sense,” Erill says, “because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

Additional bioinformatics analysis by Mascolo and Julia López-Pérez, another Ph.D. student working with Erill, revealed that MindFlayer and MiniFlayer have been co-evolving for a long time. “This satellite has been tuning in and optimizing its genome to be associated with the helper for, I would say, at least 100 million years,” Erill says, which suggests there may be many more cases of this kind of relationship waiting to be discovered.

Contamination or discovery?

This groundbreaking discovery could easily have been missed. The project started out as a typical semester in the SEA-PHAGES program—an investigative curriculum where undergraduates isolate bacteriophages from environmental samples, send them out for sequencing, and then use bioinformatics tools to analyze the results. When the sequencing lab at the University of Pittsburgh reported contamination in the sample from UMBC expected to contain the MindFlayer phage, the journey began.

The sample included one large sequence: the phage they expected. “But instead of just finding that, we also found a small sequence, which didn’t map to anything we knew,” says Erill, who is also one of the leads for UMBC’s SEA-PHAGES program, called Phage Hunters, along with Steven Caruso, principal lecturer of biological sciences. Caruso ran the isolation again, sent it out for sequencing—and got identical results.

That’s when the team pulled in deCarvalho to get a visual of what was going on with the transmission electron microscope (TEM) at UMBC’s Keith R. Porter Imaging Facility (KPIF). Without the images, the discovery would have been impossible.

“Not everyone has a TEM at their disposal,” deCarvalho notes. But with the instruments at the KPIF, deCarvalho says, “I’m able to follow up on some of these observations and validate them with imaging. There’s elements of discovery we can only make using the TEM.”

The team’s discovery sets the stage for future work to figure out how the satellite attaches, how common this phenomenon is, and much more. “It’s possible that a lot of the bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite-helper systems,” deCarvalho says, “so now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems.”

END

UMBC team makes first-ever observation of a virus attaching to another virus

Results suggest many more similar systems exist to discover

2023-11-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research connecting gut bacteria and oxytocin provides a new mechanism for microbiome-promoted health benefits

2023-11-02

The gut microbiome, a community of trillions of microbes living in the human intestines, has an increasing reputation for affecting not only gut health but also the health of organs distant from the gut. For most microbes in the intestine, the details of how they can affect other organs remain unclear, but for gut resident bacteria L. reuteri the pieces of the puzzle are beginning to fall into place.

“L. reuteri is one of such bacteria that can affect more than one organ in the body,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Sara Di Rienzi, ...

How “blue” and “green” appeared in a language that didn’t have words for them

2023-11-02

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- The human eye can perceive about 1 million colors, but languages have far fewer words to describe those colors. So-called basic color terms, single color words used frequently by speakers of a given language, are often employed to gauge how languages differ in their handling of color. Languages spoken in industrialized nations such as the United States, for example, tend to have about a dozen basic color terms, while languages spoken by more isolated populations often have fewer.

However, the way that a language ...

Plant populations in Cologne are adapted to their urban environments

2023-11-02

A research team from the Universities of Cologne and Potsdam and the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research has found that the regional lines of the thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), a small ruderal plant which populates the streets of Cologne, vary greatly in typical life cycle characteristics, such as the regulation of flowering and germination. This allows them to adapt their reproduction to local environmental conditions such as temperature and human disturbances. The researchers from Collaborative Research Center / Transregio 341 “Plant Ecological Genetics” found that environmental ...

Making gluten-free, sorghum-based beers easier to brew and enjoy

2023-11-02

Though beer is a popular drink worldwide, it’s usually made from barley, which leaves those with a gluten allergy or intolerance unable to enjoy the frothy beverage. Sorghum, a naturally gluten-free grain, could be an alternative, but complex preparation steps have hampered its widespread adoption by brewers. Now, researchers reporting the molecular basis behind sorghum brewing in ACS’ Journal of Proteome Research have uncovered an enzyme that could improve the future of sorghum-based beers.

Traditionally, beer brewers start with barley grains, which they malt, mash, ...

Jurassic worlds might be easier to spot than modern Earth

2023-11-02

ITHACA, N.Y. –Things may not have ended well for dinosaurs on Earth, but Cornell University astronomers say the “light fingerprint” of the conditions that enabled them to emerge here provide a crucial missing piece in our search for signs of life on planets orbiting alien stars.

Their analysis of the most recent 540 million years of Earth’s evolution, known as the Phanerozoic Eon, finds that telescopes could better detect potential chemical signatures of life in the atmosphere of an Earth-like exoplanet more closely resembling the age the dinosaurs inhabited than the ...

Archaeology: Larger-scale warfare may have occurred in Europe 1,000 years earlier

2023-11-02

A re-analysis of more than 300 sets of 5,000-year-old skeletal remains excavated from a site in Spain suggests that many of the individuals may have been casualties of the earliest period of warfare in Europe, occurring over 1,000 years before the previous earliest known larger-scale conflict in the region. The study, published in Scientific Reports, indicates that both the number of injured individuals and the disproportionately high percentage of males affected suggest that the injuries resulted from a period of conflict, potentially lasting at least months.

Conflict during the European Neolithic period (approximately 9,000 ...

Study warns API restrictions by social media platforms threaten research

2023-11-02

University researchers from the UK, Germany and South Africa warn of a threat to scientific knowledge and the future of research in a paper published in Nature Human Behaviour, outlining the implications of changes to social media Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

Over the course of 2023, numerous social media platforms including X, TikTok, and Reddit made substantial changes to their APIs – drastically reducing access or increasing charges for access, which the researchers say will in many cases make research harder.

APIs have been routinely tapped by researchers ...

Researchers engineer colloidal quasicrystals using DNA-modified building blocks

2023-11-02

Evanston, IL. --- A team of researchers from the Mirkin Group at Northwestern University’s International Institute for Nanotechnology in collaboration with the University of Michigan and the Center for Cooperative Research in Biomaterials- CIC biomaGUNE, unveils a novel methodology to engineer colloidal quasicrystals using DNA-modified building blocks. Their study will be published in the journal Nature Materials under the title "Colloidal Quasicrystals Engineered with DNA."

Characterized ...

Nanoparticle quasicrystal constructed with DNA

2023-11-02

Images

Nanoengineers have created a quasicrystal—a scientifically intriguing and technologically promising material structure—from nanoparticles using DNA, the molecule that encodes life.

The team, led by researchers at Northwestern University, the University of Michigan and the Center for Cooperative Research in Biomaterials in San Sebastian, Spain, reports the results in Nature Materials.

Unlike ordinary crystals, which are defined by a repeating structure, the patterns in quasicrystals don't repeat. Quasicrystals built from atoms can have exceptional properties—for ...

Damaging thunderstorm winds increasing in central U.S.

2023-11-02

Destructive winds that flow out of thunderstorms in the central United States are becoming more widespread with warming temperatures, according to new research by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The new study, published this week in Nature Climate Change, shows that the central U.S. experienced a fivefold increase in the geographic area affected by damaging thunderstorm straight line winds in the past 40 years. The research uses a combination of meteorological observations, very high-resolution computer modeling, and analyses of fundamental ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

[Press-News.org] UMBC team makes first-ever observation of a virus attaching to another virusResults suggest many more similar systems exist to discover