(Press-News.org) Stem cells can differentiate to replace dead and damaged cells. But how do stem cells decide which type of cell to become in a given situation? Using intestinal organoids, the group of Bon-Kyoung Koo at IMBA and the Institute for Basic Science identified a new gene, Daam1, that plays an essential role, switching on the development of secretory cells in the intestine. This finding, published on November 24 in Science Advances, opens new perspectives in cancer research.

Our bodies are, in some ways, like cars – to keep functioning, they need to be checked and repaired regularly. In the case of our bodies, any cells that are damaged or dead need to be replaced to keep organs functioning. This replacement occurs thanks to tissue-resident adult stem cells. In contrast with embryonic stem cells, which can form any cell type in the body, adult stem cells will only form the cell types that are found in the tissue they belong to. But how do tissue-specific stem cells know which cell type to give rise to? Gabriele Colozza, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Bon-Kyoung Koo at IMBA – now director at the Center for Genome Engineering, Institute for Basic Science in South Korea – decided to investigate this question using intestinal stem cells.

Intestines – a constant construction site

“In our intestines, cells are exposed to extreme conditions”, Colozza explains. Mechanical wear and tear, but also digestive enzymes and varying pH values all affect intestinal cells. In turn, stem cells in the intestine’s mucosa differentiate to form new intestinal cells. “Damaged cells have to be replaced, but it is a delicate balance between stem cell renewal and differentiation into other cell types: uncontrolled stem cell proliferation may lead to tumor formation; on the other hand, if too many stem cells differentiate, the tissue will be depleted of stem cells and ultimately unable to self-renew.”

This balance is delicately tuned by signaling pathways and feedback loops, which allow cells to communicate with each other. One important pathway is called Wnt. The Wnt pathway is known for its role in embryonic development, and if left unchecked, an overactive Wnt pathway can lead to excessive cell division and the formation of tumors.

Molecular partner identified

A well-known antagonist of Wnt signalling – keeping Wnt in check – is Rnf43, which was originally identified by Bon-Kyoung Koo. Prior to this study, Rnf43 was known to target the Wnt receptor Frizzled and mark it for degradation. “We wanted to know how Rnf43 works, and also what – in turn – controls Rnf43 and helps it to regulate Wnt signalling.” From earlier research, the scientists knew that Rnf43 on its own was not sufficient to break down the Wnt receptor Frizzled, which sits in the plasma membrane. “In our project, we used biochemical assays to identify which proteins interact with Rnf43.” A key partner of Rnf43 turned out to be the protein Daam1.

To understand how Daam1 regulates Rnf43 and affects the tissues it acts in, Colozza turned to intestinal organoids. “We found that Daam1 is required for Rnf43 to be active, so for Rnf43 to regulate Wnt signaling at all. Further work in cells showed Rnf43 needs Daam1 to move the Wnt receptor Frizzled into vesicles called endosomes. From the endosomes, Frizzled is shuttled to the lysosomes where it is degraded, dampening Wnt signaling”, Colozza adds.

Intestinal organoids are three-dimensional cell cultures grown from adult intestinal stem cells, allowing the researchers to mimic the intestinal mucosa. For Colozza, organoids were an opportunity to understand how Rnf43 and Daam1 affect the delicate balance of stem cell renewal and differentiation in the intestine. “We found that when we knock-out Rnf43 or Daam1, the organoids grow into tumor-like structures. These tumor-like organoids keep on growing, even if we withdraw the growth factors they usually depend on, such as R-spondin.”

Switching on Paneth cell formation

When Colozza followed up this result in mouse tissue, the researchers were in for a surprise. “When Rnf43 was missing, the intestines grew tumors – as expected. But when Daam1 was missing, no tumors grew. We were puzzled by this striking difference: how can the loss of factors in the same pathway, that behave similarly in organoids, lead to such different outcomes?”

Looking closely at the intestines, Colozza saw that intestines lacking Rnf43 were full of a specific type of secretory cells, the Paneth cells. Intestines lacking Daam1, on the other hand, contained no extra Paneth cells. Paneth cells secrete growth factors, such as Wnt, that stimulate cell division. “Daam1 is required for the efficient formation of Paneth cells. When Daam1 is active, stem cells differentiate to form Paneth cells. When Daam1 is not active, the stem cells differentiate into another cell type.”

Tumors modify their niche to grow

This link between the molecular results and Paneth cells explains the puzzling difference between intestines and organoids. “In organoid culture, we scientists provide growth factors, so the knockout of both Rnf43 and Daam1 lead to tumor-like organoids. But in the intestine, there is no little scientist providing growth factors. Instead, Paneth cells provide growth factors, like Wnt, and create the right conditions for stem cells to survive and divide. When Paneth cells are lacking – such as when Daam1 is not active to drive cells into becoming Paneth cells – stem cells will not divide much. But when there are too many Paneth cells – such as in intestines lacking Rnf43 – the excessive growth factors can contribute to the formation of tumors.”

Colozza’s and colleagues’ study is the first genetic proof that Daam1, a member of the non-canonical Wnt pathway, is important for specifying Paneth cells, and directly involved in the development of this crucial secretory cell. The results also shed light on the importance of the stem cell niche. “We show that tumor cells modify their microenvironment, and influence their supporting environment so that they can grow better.”

END

Decoding cell fate: Key mechanism in stem cell switch identified

2023-11-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The Fens of eastern England once held vast woodlands, study finds

2023-11-24

The Fens of eastern England, a low-lying, extremely flat landscape dominated by agricultural fields, was once a vast woodland filled with huge yew trees, according to new research.

Scientists from the University of Cambridge studied hundreds of tree trunks, dug up by Fenland farmers while ploughing their fields. The team found that most of the ancient wood came from yew trees that populated the area between four and five thousand years ago.

These trees, which are a nuisance when they jam farming equipment during ploughing, contain a treasure trove of perfectly preserved ...

Premature death of autistic people in the UK investigated for the first time

2023-11-24

A new study led by UCL researchers confirms that autistic people experience a reduced life expectancy, however the number of years of life lost may not be as high as previously claimed.

The research, published in The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, is the first to estimate the life expectancy and years of life lost by autistic people living in the UK.

The team used anonymised data from GP practices throughout the UK to study people who received an autism diagnosis between 1989 to 2019. They ...

How do plants determine where the light is coming from ?

2023-11-23

Plants have no visual organs, so how do they know where light comes from? In an original study combining expertise in biology and engineering, the team led by Prof Christian Fankhauser at UNIL, in collaboration with colleagues at EPFL, has uncovered that a light-sensitive plant tissue uses the optical properties of the interface between air and water to generate a light gradient that is 'visible' to the plant. These results have been published in the journal Science.

The majority of living organisms (micro-organisms, plants and animals) have the ability to determine the origin of a light source, even in the absence of a sight organ comparable to the eye. This information is invaluable ...

Study provides fresh insights into antibiotic resistance, fitness landscapes

2023-11-23

E. coli bacteria may be far more capable at evolving antibiotic resistance than scientists previously thought, according to a new study published in Science on November 24.

Led by SFI External Professor Andreas Wagner, the researchers experimentally mapped more than 260,000 possible mutations of an E. coli protein that is essential for the bacteria’s survival when exposed to the antibiotic trimethoprim.

Over the course of thousands of highly realistic digital simulations, the researchers then found that 75% of all possible evolutionary paths of the E. coli protein ultimately ...

Separating out signals recorded at the seafloor

2023-11-23

Blame it on plate tectonics. The deep ocean is never preserved, but instead is lost to time as the seafloor is subducted. Geologists are mostly left with shallower rocks from closer to the shoreline to inform their studies of Earth history.

“We have only a good record of the deep ocean for the last ~180 million years,” said David Fike, the Glassberg/Greensfelder Distinguished University Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “Everything else is just shallow-water deposits. So it’s really important to understand the bias that might be present when we look ...

Dolomite crystals require cycles of saturation conditions to grow

2023-11-23

Addressing the long-standing “dolomite problem,” an oddity that has vexed scientists for nearly 200 years, researchers report that dolomite crystals require cycling of saturation conditions to grow. The findings provide new insights into how dolomite is formed and why modern dolomite is primarily found in natural environments with pH or salinity fluctuations. Dolomite – a calcium magnesium carbonate – is one of the major minerals in carbonate rocks, accounting for nearly 30% of the sedimentary carbonate minerality in Earth’s crust. However, despite its geological abundance, dolomite does not readily grow under laboratory conditions, ...

FLSHclust, a new algorithm, reveals rare and previously unknown CRISPR-Cas systems

2023-11-23

Using a new algorithm called FLSHclust (“flash clust”), researchers have discovered 188 rare and previously unknown CRISPR-linked gene modules – including a novel type VII CRISPR-Cas system – among billions of protein sequences. The approach and its findings provide novel opportunities for harnessing CRISPR systems and understanding the vast functional diversity of microbial proteins. CRISPR systems have been leveraged to develop a growing suite of novel biomolecular approaches, including CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing. The discovery ...

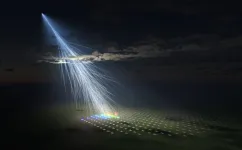

Extremely energetic cosmic ray detected, but with no obvious source

2023-11-23

An extremely energetic cosmic ray – an extragalactic particle with an energy exceeding ~240 exa-electron volts (EeV) – has been detected by the Telescope Array experiment’s surface detector, researchers report. However, according to the findings, its arrival direction shows no obvious source. Ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) are subatomic charged particles from space with energies greater than 1 EeV – roughly a million times as high as the energy reached by human-made particle accelerators. Although low-energy cosmic rays primarily emanate from the sun, the origins of rarer UHECRs are thought to be related to the most energetic phenomena in the Universe, ...

Telescope Array detects second highest-energy cosmic ray ever

2023-11-23

In 1991, the University of Utah Fly’s Eye experiment detected the highest-energy cosmic ray ever observed. Later dubbed the Oh-My-God particle, the cosmic ray’s energy shocked astrophysicists. Nothing in our galaxy had the power to produce it, and the particle had more energy than was theoretically possible for cosmic rays traveling to Earth from other galaxies. Simply put, the particle should not exist.

The Telescope Array has since observed more than 30 ultra-high-energy cosmic rays, though none approaching the Oh-My-God-level energy. No observations have yet revealed ...

'Dolomite Problem': 200-year-old geology mystery resolved

2023-11-23

Images // Video

ANN ARBOR—For 200 years, scientists have failed to grow a common mineral in the laboratory under the conditions believed to have formed it naturally. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Michigan and Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan have finally pulled it off, thanks to a new theory developed from atomic simulations.

Their success resolves a long-standing geology mystery called the "Dolomite Problem." Dolomite—a key mineral in the Dolomite mountains in Italy, Niagara Falls, the White Cliffs of Dover and Utah's Hoodoos—is very abundant in rocks older than 100 million years, but nearly absent in younger ...