(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Dec. 14, 2023 – Spinal cord stimulation can elicit sensation in the missing foot and alleviate phantom limb pain in people with lower limb amputations, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine rehabilitation scientists report today.

Pressure sensors on the insole of a prosthetic foot triggered electrical pulses that were then delivered to a participants’ spinal cord. Researchers found that this sensory feedback also improved balance and gait stability. The proof-of-concept study was done in collaboration with Carnegie Mellon University and University of Chicago researchers and reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“We are using electrodes and stimulation devices that are already frequently used in the clinic and that physicians know how to implant,” said senior author Lee Fisher, Ph.D., associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Pitt. “We are leveraging those technologies to produce meaningful improvement in function and reduction of pain. That’s exciting and we’ve been building it for a while.”

Among 1.5 million Americans who live with lower-limb amputation, 8 out of 10 experience some degree of chronic pain perceived as though coming from the missing leg or foot. This phantom limb pain often does not respond to pain medications and dramatically impairs the quality of life. In addition, because even the most technically sophisticated prosthetics are not equipped with sensory feedback functionality, amputees remain prone to balance deficits and falls, which limit their mobility even further.

Unlike the typical stimulation system that works by shutting down pain neurons by overriding them with another sensory signal — similar to how rubbing your sore elbow helps relieve the pain — Fisher’s group leveraged the existing spinal cord stimulation technology to restore sensory feedback by replacing the severed connections between sensory neurons in the missing foot and the central nervous system.

To enable researchers to modulate the intensity of sensations in response to varying pressure on a prosthetic foot during walking, a pair of thin electrode strands implanted over the top of the spinal cord in the lower back was connected to a cell phone-sized stimulation device delivering electric pulses of varying amplitude and frequency. The leads were implanted for one to three months and removed after the trial ended, in accordance with the study design.

Unlike previous research done by other groups, Fisher and team were able to exert active control of spinal cord stimulation parameters to control stimulation in real-time while subjects engaged their prosthetic leg to stand or walk.

In addition to clinically meaningful improvement in balance control and gait even in the most challenging conditions, such as standing on a moving platform with eyes closed, participants reported an average 70% reduction in phantom limb pain — a highly meaningful outcome given the lack of clinically available treatment options.

The beauty of this technology lies in its versatility: the pilot study showed that it can work in people with extensive peripheral nerve damage due to chronic conditions, such as diabetes, or in people with traumatic amputations. It also doesn’t require costly custom-made electrodes or uncommon surgical procedures, making it easier to scale up on a national level.

“We are able to produce sensations as long as the spinal cord is intact,” said Fisher. “Our approach has the potential to become an important intervention for lower-limb amputation and, with proper support from industry partners, translated into the clinic in the next five years.”

Other authors of this study are Ameya Nanivadekar, Ph.D., Rohit Bose, B.S., Bailey Petersen, D.P.T., Ph.D., Tyler Madonna, B.S., Beatrice Barra, Ph.D., Isaiah Levy, M.D., Eric Helm, M.D., Vincent Miele, M.D., Michael Boninger, M.D., and Marco Capogrosso, Ph.D., all of Pitt; Devapratim Sarma, Ph.D., Juhi Farooqui, B.S., Ashley Dalrymple, Ph.D., and Douglas Weber, Ph.D., all of Carnegie Mellon University; and Elizaveta Okorokova, Ph.D., and Sliman Bensmaia, Ph.D., of the University of Chicago.

END

Spinal cord stimulation reduces pain, improves balance in people with lower limb amputation

2023-12-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Eating meals early could reduce cardiovascular risk

2023-12-14

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death in the world according to the Global Burden of Disease study, with 18.6 million annual deaths in 2019, of which around 7.9 are attributable to diet. This means that diet plays a major role in the development and progression of these diseases. The modern lifestyle of Western societies has led to specific eating habits such as eating dinner late or skipping breakfast. In addition to light, the daily cycle of food intake (meals, snacks, etc.) alternating with periods of fasting synchronizes the peripheral clocks, or circadian rhythms, of the body’s various organs, thus ...

What do Gifted dogs have in common?

2023-12-14

All dog owners think that their pup is special. Science now has documented that some rare dogs are…even more special! They have a talent for learning hundreds of names of dog toys. Due to the extreme rarity of this phenomenon, until recently, very little was known about these dogs, as most of the studies that documented this ability included only a small sample of one or two dogs. In a new study published in the Journal Scientific Reports, researchers from the Family Dog Project (ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest) shed new light on the characteristics of these exceptional dogs.

In ...

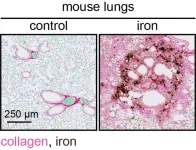

Iron accumulation: a new insight into fibrotic diseases

2023-12-14

Researchers at IRB Barcelona reveal the pivotal role of iron accumulation in the development of fibrotic diseases and propose that iron detection via MRI can serve to diagnose fibrosis.

Fibrotic diseases account for 45% of all mortality in developed countries.

Published in Nature Metabolism, the study points to new therapeutic opportunities that target iron.

Barcelona, 14 December 2023 – Fibrosis is associated with various chronic and life-threatening conditions, including pulmonary fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, kidney disease, and cardiovascular diseases, ...

Facial symmetry doesn’t explain “beer goggles”

2023-12-14

If you thought blurry eyes were to blame for the “beer goggles” phenomenon, think again.

Scientists from the University of Portsmouth have tested the popular theory that people are more likely to find someone attractive while drunk, because their faces appear more symmetrical.

The term “beer goggles” has been used for decades to describe when a person finds themselves sexually attracted to someone while intoxicated, but not sober.

One possible explanation for the effect is that alcohol impairs the drinker’s ability to detect facial asymmetry, ...

New study eyes nutrition-rich chia seed for potential to improve human health

2023-12-14

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University scientists have sequenced the chia genome and in doing so provided a blueprint for future research that capitalizes on the nutritional and human health benefits of the plant.

In the just-published paper, the researchers identified chia genes associated with improving nutrition and sought after properties for pharmaceuticals that could be used to treat everything from cancer to high blood pressure. The seeds of the chia plant have received widespread attention in recent years because of the nutritional punch they pack.

Others have sequenced the chia genome, but this paper provides a more detailed look at the molecular ...

Were Neanderthals morning people ?

2023-12-14

A new paper in Genome Biology and Evolution, published by Oxford University Press, finds that genetic material from Neanderthal ancestors may have contributed to the propensity of some people today to be “early risers,” the sort of people who are more comfortable getting up and going to bed earlier.

All anatomically modern humans trace their origin to Africa around 300 thousand years ago, where environmental factors shaped many of their biological features. Approximately seventy-thousand years ago, the ancestors ...

Mice with humanized immune systems to test cancer immunotherapies

2023-12-14

Mice with human immune cells are a new way of testing anti-cancer drugs targeting the immune system in pre-clinical studies. Using their new model, the Kobe University research team successfully tested a new therapeutic approach that blindfolds immune cells to the body’s self-recognition system and so makes them attack tumor cells.

Cancer cells display structures on their surface that identify them as part of the self and thus prevent them from being ingested by macrophages, a type of immune cell. Cancer immunotherapy aims at disrupting these recognition systems. Previous studies showed that a substance that blinds macrophages to one of ...

Quantum batteries break causality

2023-12-14

Batteries that exploit quantum phenomena to gain, distribute and store power promise to surpass the abilities and usefulness of conventional chemical batteries in certain low-power applications. For the first time, researchers including those from the University of Tokyo take advantage of an unintuitive quantum process that disregards the conventional notion of causality to improve the performance of so-called quantum batteries, bringing this future technology a little closer to reality.

When you hear the word “quantum,” the physics governing the subatomic world, developments in ...

Mothers and children have their birthday in the same month more often than you’d think – and here’s why

2023-12-14

Do you celebrate your birthday in the same month as your mum? If so, you are not alone. The phenomenon occurs more commonly than expected – a new study of millions of families has revealed.

Siblings also tend to share month of birth with each other, as do children and fathers, the analysis of 12 years’ worth of data shows, whilst parents are also born in the same month as one another more often than would be predicted.

Previous research has found that women’s season of ...

Bats declined as Britain felled trees for colonial shipbuilding

2023-12-14

Bat numbers declined as Britain’s trees were felled for shipbuilding in the early colonial period, new research shows.

The study, by the University of Exeter and the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT), found Britain’s Western barbastelle bat populations have dropped by 99% over several hundred years.

Animals’ DNA can be analysed to discover a “signature” of the past, including periods when populations declined, leading to more inbreeding and less genetic diversity.

Scientists used this method to discover the historic decline ...