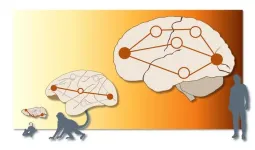

(Press-News.org) In a study comparing human brain communication networks with those of macaques and mice, EPFL researchers found that only the human brains transmitted information via multiple parallel pathways, yielding new insights into mammalian evolution.

When describing brain communication networks, EPFL senior postdoctoral researcher Alessandra Griffa likes to use travel metaphors. Brain signals are sent from a source to a target, establishing a polysynaptic pathway that intersects multiple brain regions “like a road with many stops along the way.”

She explains that structural brain connectivity pathways have already been observed based on networks (“roads”) of neuronal fibers. But as a scientist in the Medical Image Processing Lab (MIP:Lab) in EPFL’s School of Engineering, and a research coordinator at CHUV’s Leenaards Memory Centre, Griffa wanted to follow patterns of information transmission to see how messages are sent and received. In a study recently published in Nature Communications, she worked with MIP:Lab head Dimitri Van de Ville and SNSF Ambizione Fellow Enrico Amico to create “brain traffic maps” that could be compared between humans and other mammals.

To achieve this, the researchers used open-source diffusion (DWI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from humans, macaques, and mice, which was gathered while subjects were awake and at rest. The DWI scans allowed the scientists to reconstruct the brain “road maps”, and the fMRI scans allowed them to see different brain regions light up along each “road”, which indicated that these pathways were relaying neural information.

They analyzed the multimodal MRI data using information and graph theory, and Griffa says that it is this novel combination of methods that yielded fresh insights.

“What’s new in our study is the use of multimodal data in a single model combining two branches of mathematics: graph theory, which describes the polysynaptic ‘roadmaps’; and information theory, which maps information transmission (or ‘traffic’) via the roads. The basic principle is that messages passed from a source to a target remain unchanged or are further degraded at each stop along the road, like the telephone game we played as children.”

The researchers’ approach revealed that in the non-human brains, information was sent along a single “road”, while in humans, there were multiple parallel pathways between the same source and target. Furthermore, these parallel pathways were as unique as fingerprints, and could be used to identify individuals.

“Such parallel processing in human brains has been hypothesized, but never observed before at a whole-brain level,” Griffa summarizes.

Potential insights for evolution and medicine

Griffa says that the beauty of the researchers’ model is its simplicity, and its inspiration of new perspectives and research avenues in evolution and computational neuroscience. For example, the findings can be linked to the expansion of human brain volume over time, which has given rise to more complex connectivity patterns.

“We could hypothesize that these parallel information streams allow for multiple representations of reality, and the ability to perform abstract functions specific to humans.”

She adds that although this hypothesis is only speculative, as the Nature Communications study involved no testing of subjects’ computational or cognitive ability, these are questions that she would like to explore in the future.

“We looked at how information travels, so an interesting next step would be to model more complex processes to study how information is combined and processed in the brain to create something new.”

As a memory and cognition researcher, she is especially interested in using the model developed in the study to investigate if parallel information transmission could confer resilience to brain networks, and potentially play a role in neurorehabilitation after brain injury, or in the prevention of cognitive decline in pathologies of advanced age.

“Some people age healthily, while others experience cognitive decline, so we’d like to see if there is a relationship between this difference and the presence of parallel information streams, and whether they could be trained to compensate neurodegenerative processes.”

Griffa, A., Mach, M., Dedelley, J. et al. Evidence for increased parallel information transmission in human brain networks compared to macaques and male mice. Nat Commun 14, 8216 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43971-z.

END

More parallel ‘traffic' observed in human brains than in animals

In a study comparing human brain communication networks with those of macaques and mice, EPFL researchers found that only the human brains transmitted information via multiple parallel pathways, yielding new insights into mammalian evolution.

2023-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

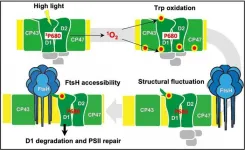

The role of oxidized tryptophan residues in repairing damaged photosystem II protein

2023-12-18

Photosynthesis refers to the fundamental biological process of the conversion of light energy into chemical energy by chlorophyll (a green pigment) containing plants. This seemingly routine process in plants sustains all the biological life and activities on Earth. First reaction of photosynthesis occurs at a site called photosystem II (PSII), present on the thylakoid membrane in the chloroplast where light energy is transferred to chlorophyll molecules. PSII is made up of a complex group of proteins, including the D1 and D2 reaction center proteins.

Light ...

Breaking the mold: Zarbio and Georgia State scientists unveil game-changing theory on Alzheimer's disease

2023-12-18

Despite affecting millions worldwide, Alzheimer's disease (AD) has long lacked effective treatments due to a fundamental inadequacy of our understanding of its etiology and pathogenesis. The absence of an integrative theory connecting the molecular origins of AD with disturbances at the organelle and cell levels, changes in relevant biomarkers, and population-level prevalence has hindered progress. Even though most scientists only hope that an integrative theory of AD will emerge soon, scientists from Zarbio and Georgia State University discovered sufficient data to formulate a framework for such a theory.

The molecular and cellular ...

Scientists collect aardvark poop to understand how the species is impacted by climate in Africa

2023-12-18

CORVALLIS, Ore. – In a first-of-its-kind study of aardvarks, Oregon State University researchers spent months in sub-Saharan Africa collecting poop from the animal and concluded that aridification of the landscape is isolating them, which they say could have implications for their long-term survival.

“Everyone had heard of aardvarks and they are considered very ecologically important but there has been little study of them,” said Clint Epps, a wildlife biologist at Oregon State. “We wanted to see if we could collect enough data to begin to understand them.”

In ...

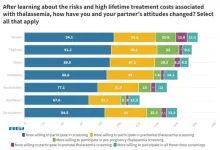

Thalassemia screening in Thailand: Medical Sciences Dean advocates for elevated trust

2023-12-18

- Insights from Professor Sakorn Pornprasert, Dean, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences at Chiang Mai University, on raising thalassemia awareness in Thailand.

Thalassemia, a genetic disorder affecting hemoglobin production, poses a significant public health challenge in Thailand, with a high prevalence and substantial healthcare costs. According to Thailand's Ministry of Public Health, approximately 18-24 million or 30-40 percent of the Thai population carries the thalassemia gene.

Professor Sakorn Pornprasert, Dean, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, shared his views on BGI Genomics Global 2023 State of Thalassemia Awareness ...

Lung nodule program provides benefits patients ineligible for lung cancer screening

2023-12-18

(Denver—December 18, 2023) – Adopting a lung nodule program (LNP) may increase the detection of early lung cancer for patients who are not eligible for lung cancer screening under existing age eligibility criteria, according to a study published in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology, an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

LNPs are established to follow up on lung nodules that are frequently identified during routine imaging for reasons other than suspected lung cancer or lung cancer screening.

The research was conducted by a team led by Dr. Raymond U. Osarogiagbon, MBBS, FACP, chief scientist ...

Multi-site study reveals addressable socioeconomic barriers to prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects

2023-12-18

Prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defects – the most common birth defects in the United States – is associated with improved outcomes. Despite its importance, however, overall prevalence of prenatal diagnosis is low (12-50 percent). A recent multi-center study surveyed caretakers of infants who received congenital heart surgery in the Chicago area and found that social determinants or influencers of health constitute significant barriers to prenatal diagnosis from the patients’ perspective.

In ...

Wildfires increasing across eastern U.S., new study reveals

2023-12-18

In a new analysis of data spanning more than three decades in the eastern United States, a team of scientists found a concerning trend – an increasing number of wildfires across a large swath of America.

“It’s a serious issue that people aren’t paying enough attention to: We have a rising incidence of wildfires across several regions of the U.S., not only in the West,” said Victoria Donovan, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of forest management at the UF/IFAS ...

Nurse aide turnover linked to scheduling decisions

2023-12-18

Long-term care facilities that scheduled part-time Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) with more hours and more consistently with the same co-workers had reduced turnover, according to research led by Washington State University. The findings could help address staffing challenges that affect millions of patients at long-term care facilities nationwide.

Using a model based on real scheduling data of thousands of nurse aides, the researchers estimated that a one-hour increase in CNAs’ weekly hours worked could reduce turnover by 1.9%. Also, the analysis found that by scheduling ...

TAMEST names Nidhi Sahni, Ph.D., as the Recipient of the 2024 Mary Beth Maddox Award & Lectureship

2023-12-18

AUSTIN/HOUSTON – TAMEST (Texas Academy of Medicine, Engineering, Science and Technology) has announced Nidhi Sahni, Ph.D., The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, as the recipient of the 2024 Mary Beth Maddox Award and Lectureship in cancer research. She was chosen for her role in identifying novel biomarkers and drug targets, which are expected to have a significant impact on cancer by translating into more effective prognosis and therapy for the disease.

The Mary Beth Maddox Award and Lectureship recognizes women scientists in Texas bringing new ideas and innovations to the fight ...

Do genes that code athletic heart enlargement carry a risk of future heart problems?

2023-12-18

A new landmark study involving 281 elite athletes from Australia and Belgium has revealed one in six have measures that would normally suggest reduced heart function.

Genetic analysis published in Circulation conducted by scientists in Australia and Belgium revealed those athletes also had an enrichment of genes associated with heart muscle disease.

Thus, a genetic predisposition may be ‘stressed’ by exercise to cause profound heart changes. The international collaboration will continue to monitor the athletes over the long-term to determine the consequences on their heart health.

Associate Professor Andre la Gerche, who heads the HEART Laboratory that is jointly ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

White House autism briefing linked to swift shifts in prescribing patterns, study finds

Specialist palliative care can save the NHS up to £8,000 per person and improves quality of life

New research warns charities against ‘AI shortcut’ to empathy

Cannabis compounds show promise in fighting fatty liver disease

Study in mice reveals the brain circuits behind why we help others

Online forum to explore how organic carbon amendments can improve soil health while storing carbon

Turning agricultural plastic waste into valuable chemicals with biochar catalysts

Hidden viral networks in soil microplastics may shape the future of sustainable agriculture

Americans don’t just fear driverless cars will crash — they fear mass job losses

Mayo Clinic researchers find combination therapy reduces effects of ‘zombie cells’ in diabetic kidney disease

Preventing breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors using genomic findings

Carbon nanotube fiber ‘textile’ heaters could help industry electrify high-temperature gas heating

Improving your biological age gap is associated with better brain health

Learning makes brain cells work together, not apart

Engineers improve infrared devices using century-old materials

Physicists mathematically create the first ‘ideal glass’

Microbe exposure may not protect against developing allergic disease

Forest damage in Europe to rise by around 20% by 2100 even if warming is limited to 2°C

Rapid population growth helped koala’s recovery from severe genetic bottleneck

CAR-expressing astrocytes target and clear amyloid-β in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease

Unique Rubisco subunit boosts carbon assimilation in land plants

Climate change will drive increasing forest disturbances across Europe throughout the next century

Enhanced brain cells clear away dementia-related proteins

This odd little plant could help turbocharge crop yields

Flipped chromosomal segments drive natural selection

Whole-genome study of koalas transforms how we understand genetic risk in endangered species

Worcester Polytechnic Institute identifies new tool for predicting Alzheimer’s disease

HSS studies highlight advantages of osseointegration for people with an amputation

Buck Institute launches Healthspan Horizons to turn long-term health data into Actionable healthspan insights

University of Ottawa Heart Institute, the University of Ottawa and McGill University launch ARCHIMEDES to advance health research in Canada

[Press-News.org] More parallel ‘traffic' observed in human brains than in animalsIn a study comparing human brain communication networks with those of macaques and mice, EPFL researchers found that only the human brains transmitted information via multiple parallel pathways, yielding new insights into mammalian evolution.