(Press-News.org) Researchers led by a University of California, Berkeley, comparative psychologist have found that great apes and chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, can recognize groupmates they haven't seen in over two decades — evidence of what’s believed to be the longest-lasting nonhuman memory ever recorded.

The findings also bolster the theory that long-term memory in humans, chimpanzees and bonobos likely comes from our shared common ancestor that lived between 6 million and 9 million years ago.

The team used infrared eye-tracking cameras to record where bonobos and chimps gazed when they were shown side-by-side images of other bonobos or chimps. One picture was of a stranger; the other was of a bonobo or chimp that the participant had lived with for a year or more.

Participants' eyes lingered significantly longer on images of those with whom they had previously lived, the researchers found, suggesting some degree of recognition. In one case, a bonobo named Louise had not seen her sister, Loretta, or nephew, Erin, for over 26 years. But when researchers showed Louise their images, her eyes homed in on the photos.

"These animals have a rich recognition of each other," said Laura Simone Lewis, a UC President's Postdoctoral Fellow in Berkeley's psychology department and lead author of the study, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

What's more, participants looked longer at individuals with whom they had had more positive, as compared with antagonistic, relationships. In other words, they seemed to recognize friends more than foes.

"We don't know exactly what that representation looks like, but we know that it lasts for years," she said. "This study is showing us not how different we are from other apes, but how similar we are to them and how similar they are to us."

The findings expand what was known about long-term memory in animals and also raise questions central to evolutionary biology and psychology. Chief among them: How did humans develop such good long-term memory?

Understanding the links between our vivid, episodic memory and the recall of other animals has long been a research puzzle. Previous studies have shown that ravens, for example, remember people who tricked them and can recall social relationships in uncanny ways. Social memory beyond just a few years had previously been documented only in dolphins, which studies have found can recognize vocalizations for up to 20 years.

"That, up until this point, has been the longest long-term social memory ever found in a nonhuman animal," Lewis said of the dolphin research. "What we're showing here is that chimps and bonobos may be able to remember that long — or longer."

Lewis's project was one born from a longtime observation among primate researchers, who often go months or years between seeing the animals they study. When they returned, bonobos and chimpanzees acted as if they were picking up right where they left off. So the researchers decided to see if that memory hunch was true.

To get answers, the team began what at times was equal parts genealogy and scrapbooking.

First, they needed to identify bonobos and chimps that had been separated from what we might view as friends or family. Sometimes, their groupmates had been relocated to other zoos to prevent in-breeding. Other times, a sibling or elder may have died while they all lived together.

With a list of pairs in hand, sprinkled across zoos in Europe and Japan, researchers needed to track down photos to show the participants. It couldn't be just any snapshot, however. They needed a quality image taken from around the time that the pair last saw one another. This was somewhat easy for the animals that were separated recently in an era rich with high-quality photos. It proved much trickier for others, like Louise's relatives, who were separated circa 1995.

The team ended up being able to show images to 26 bonobos and chimpanzees.

After setting up a computer system with sensitive cameras and non-invasive eye-tracking tools, participating animals were allowed to enter the room voluntarily. Their compensation? A bottle filled with diluted juice. (Bonobos and chimps love fruit juice and eat lots of fruit in the wild.)

As they sipped, the screens in front of them alternated between pairs of images. The cameras monitored where the animals' eyes wandered. And the computer logged the time spent on each image down to a fraction of a second — data the team would comb through months later.

"It was a really simple test: Do they look longer at their previous groupmate, or are they looking longer at the stranger?” Lewis said. “And we found that, yes, they are looking significantly longer at the pictures of their previous groupmates."

Lewis said she and others were especially concerned about how the participants might react when they were shown an image of a relative they hadn't seen in years. As the project began, zookeepers monitored the animals for signs of stress. But they didn't show any markers of agitation. Instead, when images of a once-close relative appeared on the screen, the participants would sometimes stop drinking the juice entirely, seemingly mesmerized by the image.

The study showed that something is happening with the mind in recognizing the images. What's unclear is what kind of memories they were. Could they have been rich, episodic narratives like humans have? Might there have been some fleeting curiosity about why they saw this? Can they extrapolate what those relatives might look like today?

These are the next questions for Lewis. Born and raised in Berkeley, Lewis attended Duke University and Harvard University and conducted a fellowship at the University of St. Andrews. Lewis' co-authors include researchers from Harvard, Johns Hopkins University, Kyoto University, the University of Antwerp in Belgium and the University of Konstanz in Germany.

Lewis returned to Berkeley earlier this year as a postdoctoral fellow. It was a homecoming of sorts, she said, and she plans to continue asking big questions about what our closest living ancestors can teach us about our memory. Partly it's out of a curiosity that drives science. It's also out of a determination to conserve the habitats that are home to endangered bonobos — animals that can teach us about ourselves.

"This study is reminding us how similar we are to other species walking on the planet," Lewis said. "And therefore, how important it is to protect them."

END

Move over dolphins. Chimps and bonobos can recognize long-lost friends and family — for decades

2023-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

First observation of how water molecules move near a metal electrode

2023-12-18

A collaborative team of experimental and computational physical chemists from South Korea and the United States have made an important discovery in the field of electrochemistry, shedding light on the movement of water molecules near metal electrodes. This research holds profound implications for the advancement of next-generation batteries utilizing aqueous electrolytes.

In the nanoscale realm, chemists typically utilize laser light to illuminate molecules and measure spectroscopic properties to visualize molecules. However, studying the behavior of ...

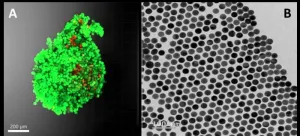

Harnessing nanotechnology to understand tumor behavior

2023-12-18

A study conducted by pre-PhD researcher Pablo S. Valera and recently published in PNAS demonstrates the potential of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to explore metabolites secreted by cancer cells in cancer research. The study, which has been led by Ikerbasque Research Professors Luis Liz-Marzán (from CIC biomaGUNE) and Arkaitz Carracedo (of CIC bioGUNE) and in which other researchers from both centers, also members of the Networking Biomedical Research Centre (CIBER), have participated as well, provides valuable information to guide more specific experiments to reveal ...

Exercise-induced Pgc-1α expression inhibits fat accumulation in aged skeletal muscles

2023-12-18

Myosteatosis, or aging-related fat accumulation in skeletal muscles, is a leading cause of declines in muscle strength and quality of life in elderly adults.

Older adults who are sedentary and develop accumulated fat in the skeletal muscle are often prescribed exercise by their doctors to combat the condition. If scientists were to develop a new therapy, such as medications, to combat myosteatosis, they would need to replicate the mechanism by which exercise might reduce fat accumulation in muscles.

Fibro-adipogenic ...

NASA’s Webb rings in holidays with ringed planet Uranus

2023-12-18

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope recently trained its sights on unusual and enigmatic Uranus, an ice giant that spins on its side. Webb captured this dynamic world with rings, moons, storms, and other atmospheric features – including a seasonal polar cap. The image expands upon a two-color version released earlier this year, adding additional wavelength coverage for a more detailed look.

With its exquisite sensitivity, Webb captured Uranus’ dim inner and outer rings, including the ...

Memory research: Breathing in sleep impacts memory processes

2023-12-18

How are memories consolidated during sleep? In 2021, researchers led by Dr. Thomas Schreiner, leader of the Emmy Noether junior research group at LMU’s Department of Psychology, had already shown there was a direct relationship between the emergence of certain sleep-related brain activity patterns and the reactivation of memory contents during sleep. However, it was still unclear whether these rhythms are orchestrated by a central pacemaker. So the researchers joined up with scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin and the University of Oxford to reanalyze the data. Their results have identified ...

Alexander Zholents recognized with 2023 Dieter Möhl Award

2023-12-18

Zholents was honored for his work on the theory of optical stochastic cooling.

Alexander Zholents, a senior physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and distinguished fellow in the Accelerator Systems division is one of the recipients of this year’s Dieter Möhl Award.

The award is presented by CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics. It is in tribute to the late Dieter Möhl, a pioneer in the realm of particle beam cooling. The awards celebrate both early career and lifetime achievements in the field of beam cooling and its applications.

“I am deeply honored to receive this award,” said Zholents. “The ...

Unraveling predisposition in bilateral Wilms tumor

2023-12-18

(Memphis, Tenn.—December 18, 2023) Children with bilateral Wilms tumor have a tumor in each of their kidneys — a condition that strongly suggests an underlying genetic or epigenetic predisposition driving the disease. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital gathered a large cohort of bilateral Wilms tumor samples and conducted analyses to assess which factors contribute to predisposition comprehensively. The work has implications for counseling patient families, guiding treatment decisions and informing the design of future clinical trials. The study was published today in Nature Communications.

Having tumors in ...

Feelings of impatience evolve over time, study says

2023-12-18

A new study answers a timely question: What is the hardest part of waiting? Consumers do plenty of it—online, in line, in traffic, or for deliveries. And now we know it’s the final phase that’s most problematic for them.

In this season of joyful—and not-so-joyful—anticipation, the research has deep implications for marketers and psychological insights for us all, says Annabelle Roberts, coauthor and assistant professor of marketing at the University of Texas McCombs School of Business. The paper shows:

It’s better for companies to communicate possible delays early in the wait;

It’s better for ...

Little bacterium may make big impact on rare-earth processing

2023-12-18

ITHACA, N.Y. - A tiny, hard-working bacterium – which weighs one-trillionth of a gram – may soon have a large influence on processing rare earth elements in an eco-friendly way.

In a new study, Cornell University scientists show that genetically engineering this bacterium could improve the efficiency for the purification of elements found in smartphones, computers, electric cars and wind turbines, and could even boost global economic supply chains.

Vibrio natriegens, the bacterium, offers a sustainable ...

AI generates proteins with exceptional binding strengths

2023-12-18

A new study Dec. 18 in Nature reports an AI-driven advance in biotechnology with implications for drug development, disease detection, and environmental monitoring. Scientists at the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington School of Medicine used software to create protein molecules that bind with exceptionally high affinity and specificity to a variety of challenging biomarkers, including human hormones. Notably, the scientists achieved the highest interaction strength ever reported between a computer-generated biomolecule and its target.

Senior author David Baker, professor of biochemistry at UW Medicine, ...