(Press-News.org) Apes recognize photos of groupmates they haven’t seen for more than 25 years and respond even more enthusiastically to pictures of their friends, a new study finds.

The work, which demonstrates the longest-lasting social memory ever documented outside of humans, and underscores how human culture evolved from the common ancestors we share with apes, our closest relatives, was published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Chimpanzees and bonobos recognize individuals even though they haven’t seen them for multiple decades,” said senior author Christopher Krupenye, an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies animal cognition. “And then there’s this small but significant pattern of greater attention toward individuals with whom they had more positive relationships. It suggests that this is more than just familiarity, that they’re keeping track of aspects of the quality of these social relationships.”

Adds lead author Laura Lewis, a biological anthropologist and comparative psychologist at University of California, Berkeley: “We tend to think about great apes as quite different from ourselves but we have really seen these animals as possessing cognitive mechanisms that are very similar to our own, including memory. And I think that is what’s so exciting about this study.”

The research team was inspired to pursue the question of how long apes remember their peers because of their own experiences working with apes—the sense that the animals recognized them when they’d visit, even if they’d been away for a long while.

“You have the impression that they’re responding like they recognize you and that to them you’re really different from the average zoo guest,” Krupenye said. “They’re excited to see you again. So our goal with this study was to ask, empirically, if that’s the case: Do they really have a robust lasting memory for familiar social partners?”

The team worked with chimpanzees and bonobos at Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland, Planckendael Zoo in Belgium, and Kumamoto Sanctuary in Japan. The researchers collected photographs of apes that had either left the zoos or died, individuals that participants hadn’t seen for at least nine months and in some cases for as long as 26 years. The researchers also collected information about the relationships each participant had with former groupmates—if there had been positive or negative interactions between them, etc.

The team invited apes to participate in the experiment by offering them juice, and while they sipped it, the apes where shown two side-by-side photographs—apes they’d once known and total strangers. Using a non-invasive eye-tracking device, the team measured where the apes looked and for how long, speculating they’d look longer at apes they recognized.

The apes looked significantly longer at former groupmates, no matter how long they’d been apart. And they looked longer still at their former friends, those they’d had more positive interactions with.

In the most extreme case during the experiment, bonobo Louise had not seen her sister Loretta nor nephew Erin for more than 26 years at the time of testing. She showed a strikingly robust looking bias toward both of them over eight trials.

The results suggest great ape social memory could last beyond 26 years, the majority of their 40 to 60-year average lifespan, and could be comparable to that of humans, which begins to decline after 15 years but can persist as long as 48 years after separation. Such long lasting social memory in both humans and our closest relatives suggests that this kind of memory was likely already present millions of years ago in our common evolutionary ancestors. This memory likely forged a foundation for the evolution of human culture and enabled the emergence of uniquely-human forms of interaction such as intergroup trade where relationships are maintained over many years of separation, the authors said.

The idea that apes remember information about the quality of their relationships, years beyond any potential functionality, is another novel and human-like finding of the work, Krupenye said.

“This pattern of social relationships shaping long-term memory in chimpanzees and bonobos is similar to what we see in humans, that our own social relationships also seem to shape our long-term memory of individuals,” Lewis said.

The work also raises the questions of whether the apes are missing individuals they’re no longer with, especially their friends and family.

“The idea that they do remember others and therefore they may miss these individuals is really a powerful cognitive mechanism and something that's been thought of as uniquely human,” Lewis said. “Our study doesn’t determine they are doing this, but it raises questions about the possibility that they may have the ability to do so.”

The team hopes the findings deepen people’s understanding of the great apes, all of which are endangered species, while shedding new light on how deeply they could be affected when poaching and deforestation separate them from their groupmates.

“This work clearly shows how fundamental and long lasting these relationships are. Disruption to those relationships is likely very damaging,” Krupenye said.

The team would next like to explore whether these long-lasting social memories are special to great apes or something experienced by other primates. They would also like to test how rich the memories of apes are, if, for instance, they possess lasting memories for experiences as well as individuals.

The work was made possible by Templeton World Charity Foundation grant TWCF-20647 and CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholars program.

Authors include: Erin G. Wessling, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University and the University of Göttingen; Fumihiro Kano, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior; Jeroen M. G. Stevens of Odisee University in Belgium, and Josep Call of University of St Andrews.

END

Apes remember friends they haven’t seen for decades

Study finds the longest lasting non-human social memories ever documented

2023-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists might be using a flawed strategy to predict how species will fare under climate change

2023-12-18

EMBARGO LIFTS DEC. 18, 2023, AT 3:00 PM U.S. EASTERN TIME

As the world heats up, and the climate shifts, life will migrate, adapt or go extinct. For decades, scientists have deployed a specific method to predict how a species will fare during this time of great change. But according to new research, that method might be producing results that are misleading or wrong.

University of Arizona researchers and their team members at the U.S. Forest Service and Brown University found that the method – commonly referred to as space-for-time substitution – failed to accurately predict how a widespread tree of the Western U.S. called the ...

Mesopotamian bricks unveil the strength of Earth’s ancient magnetic field

2023-12-18

Ancient bricks inscribed with the names of Mesopotamian kings have yielded important insights into a mysterious anomaly in Earth’s magnetic field 3,000 years ago, according to a new study involving UCL researchers.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), describes how changes in the Earth’s magnetic field imprinted on iron oxide grains within ancient clay bricks, and how scientists were able to reconstruct these changes from the names of the kings inscribed on the bricks.

The team hopes that using this “archaeomagnetism,” which looks for signatures ...

Move over dolphins. Chimps and bonobos can recognize long-lost friends and family — for decades

2023-12-18

Researchers led by a University of California, Berkeley, comparative psychologist have found that great apes and chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, can recognize groupmates they haven't seen in over two decades — evidence of what’s believed to be the longest-lasting nonhuman memory ever recorded.

The findings also bolster the theory that long-term memory in humans, chimpanzees and bonobos likely comes from our shared common ancestor that lived between 6 million and 9 million years ago.

The team used infrared eye-tracking cameras to record where bonobos and chimps gazed when they were shown side-by-side images of other bonobos ...

First observation of how water molecules move near a metal electrode

2023-12-18

A collaborative team of experimental and computational physical chemists from South Korea and the United States have made an important discovery in the field of electrochemistry, shedding light on the movement of water molecules near metal electrodes. This research holds profound implications for the advancement of next-generation batteries utilizing aqueous electrolytes.

In the nanoscale realm, chemists typically utilize laser light to illuminate molecules and measure spectroscopic properties to visualize molecules. However, studying the behavior of ...

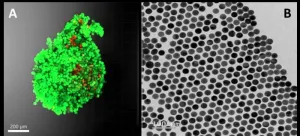

Harnessing nanotechnology to understand tumor behavior

2023-12-18

A study conducted by pre-PhD researcher Pablo S. Valera and recently published in PNAS demonstrates the potential of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to explore metabolites secreted by cancer cells in cancer research. The study, which has been led by Ikerbasque Research Professors Luis Liz-Marzán (from CIC biomaGUNE) and Arkaitz Carracedo (of CIC bioGUNE) and in which other researchers from both centers, also members of the Networking Biomedical Research Centre (CIBER), have participated as well, provides valuable information to guide more specific experiments to reveal ...

Exercise-induced Pgc-1α expression inhibits fat accumulation in aged skeletal muscles

2023-12-18

Myosteatosis, or aging-related fat accumulation in skeletal muscles, is a leading cause of declines in muscle strength and quality of life in elderly adults.

Older adults who are sedentary and develop accumulated fat in the skeletal muscle are often prescribed exercise by their doctors to combat the condition. If scientists were to develop a new therapy, such as medications, to combat myosteatosis, they would need to replicate the mechanism by which exercise might reduce fat accumulation in muscles.

Fibro-adipogenic ...

NASA’s Webb rings in holidays with ringed planet Uranus

2023-12-18

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope recently trained its sights on unusual and enigmatic Uranus, an ice giant that spins on its side. Webb captured this dynamic world with rings, moons, storms, and other atmospheric features – including a seasonal polar cap. The image expands upon a two-color version released earlier this year, adding additional wavelength coverage for a more detailed look.

With its exquisite sensitivity, Webb captured Uranus’ dim inner and outer rings, including the ...

Memory research: Breathing in sleep impacts memory processes

2023-12-18

How are memories consolidated during sleep? In 2021, researchers led by Dr. Thomas Schreiner, leader of the Emmy Noether junior research group at LMU’s Department of Psychology, had already shown there was a direct relationship between the emergence of certain sleep-related brain activity patterns and the reactivation of memory contents during sleep. However, it was still unclear whether these rhythms are orchestrated by a central pacemaker. So the researchers joined up with scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin and the University of Oxford to reanalyze the data. Their results have identified ...

Alexander Zholents recognized with 2023 Dieter Möhl Award

2023-12-18

Zholents was honored for his work on the theory of optical stochastic cooling.

Alexander Zholents, a senior physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and distinguished fellow in the Accelerator Systems division is one of the recipients of this year’s Dieter Möhl Award.

The award is presented by CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics. It is in tribute to the late Dieter Möhl, a pioneer in the realm of particle beam cooling. The awards celebrate both early career and lifetime achievements in the field of beam cooling and its applications.

“I am deeply honored to receive this award,” said Zholents. “The ...

Unraveling predisposition in bilateral Wilms tumor

2023-12-18

(Memphis, Tenn.—December 18, 2023) Children with bilateral Wilms tumor have a tumor in each of their kidneys — a condition that strongly suggests an underlying genetic or epigenetic predisposition driving the disease. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital gathered a large cohort of bilateral Wilms tumor samples and conducted analyses to assess which factors contribute to predisposition comprehensively. The work has implications for counseling patient families, guiding treatment decisions and informing the design of future clinical trials. The study was published today in Nature Communications.

Having tumors in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Apes remember friends they haven’t seen for decadesStudy finds the longest lasting non-human social memories ever documented