(Press-News.org) Autophagy, which declines with age, may hold more mysteries than researchers previously suspected. In the January 4th issue of Nature Aging, it was noted that scientists from the Buck Institute, Sanford Burnham Prebys and Rutgers University have uncovered possible novel functions for various autophagy genes, which may control different forms of disposal including misfolded proteins—and ultimately affect aging.

“While this is very basic research, this work is a reminder that it is critical for us to understand whether we have the whole story about the different genes that have been related to aging or age-related diseases,” said Professor Malene Hansen, Ph.D., Buck’s chief scientific officer, who is also the study’s co-senior author. “If the mechanism we found is conserved in other organisms, we speculate that it may play a broader role in aging than has been previously appreciated and may provide a method to improve life span.”

These new observations provide another perspective to what was traditionally thought to be occurring during autophagy.

Autophagy is a cellular “housekeeping” process that promotes health by recycling or disposing of damaged DNA and RNA and other cellular components in a multi-step degradative process. It has been shown to be a key player in preventing aging and diseases of aging, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and neurodegeneration. Notably, research has shown that autophagy genes are responsible for prolonged life span in a variety of long-lived organisms.

The classical explanation of how autophagy works is that the cellular “garbage” to be dealt with is sequestered in a membrane-surrounded vesicle, and ultimately delivered to lysosomes for degradation. However, Hansen, who has studied the role of autophagy in aging for most of her career, was intrigued by an accumulation of evidence that indicated that this was not the only process in which autophagy genes can function.

“There had been this growing notion over the last few years that genes in the early steps of autophagy were ‘moonlighting’ in processes outside of this classical lysosomal degradation,” she said. Additionally, while it is known that multiple autophagy genes are required for the increased life span, the tissue-specific roles of specific autophagy genes are not well defined.

To comprehensively investigate the role that autophagy genes play in neurons—a key cell type for neurodegenerative diseases—the team analyzed Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny worm that is frequently used to model the genetics of aging and which has a very well-studied nervous system. The researchers specifically inhibited autophagy genes functioning at each step of the process in the neurons of the animals, and found that neuronal inhibition of early-acting, but not late-acting, autophagy genes, extended life span. These initial observations were made in Dr. Hansen’s lab at Sanford Burnham Prebys in La Jolla, California, before she moved to the Buck Institute in 2021.

An unexpected aspect was that this life span extension was accompanied by a reduction in aggregated protein in the neurons (an increase is associated with Huntington’s disease, for example), and an increase in the formation of so-called exophers. These giant vesicles extruded from neurons were identified in 2017 by Dr. Monica Driscoll, a collaborator and professor at Rutgers University.

“Exophers are thought to be essentially another cellular garbage disposal method, a mega-bag of trash,” said Dr. Caroline Kumsta, co-senior author and assistant professor at SBP. “When there is either too much trash accumulating in neurons, or when the normal ‘in-house’ garbage disposal system is broken, the cellular waste is then being thrown out in these exophers.”

Interestingly, worms that formed exophers had reduced protein aggregation and lived significantly longer. This finding suggests a link between this process of this massive disposal event to overall health, said Kumsta. The team found that this process was dependent on a protein called ATG-16.2.

The study identified several new functions for the autophagy protein ATG-16.2, including in exopher formation and life span determination, which led the team to speculate that this protein plays a nontraditional and unexpected role in the aging process. If this same mechanism is operating in other organisms, it may provide a method of manipulating autophagy genes to improve neuronal health and increase life span.

“But first we have to learn more—especially how ATG-16.2 is regulated and whether it is relevant in a broader sense, in other tissues and other species,” Hansen said. The Hansen and Kumsta teams are planning on following up with a number of longevity models, including nematodes, mammalian cell cultures, human blood and mice.

“Learning if there are multiple functions around autophagy genes like ATG-16.2 is going to be super important in developing potential therapies,” Kumsta said. “It is currently very basic biology, but that is where we are in terms of knowing what those genes do.”

The traditional explanation that aging and autophagy are linked because of lysosomal degradation may need to expand to include additional pathways, which would have to be targeted differently to address the diseases and the problems that are associated with that. “It will be important to know either way,” Hansen said. “The implications of such additional functions may hold a potential paradigm shift.”

CITATION: Autophagy protein ATG-16.2 and its WD40 domain mediate the beneficial effects of inhibiting early-acting autophagy genes in C. elegans neurons'

DOI:10.1038/s43587-023-00548-1

Other Buck researchers involved in the study are Ling-Hsuan Sun, Michael Broussalian, Saam Doroodian and Dr. Hiroshi Ebata.Other SBP researchers involved in the study are Dr. Yongzhi Yang, Caitlin Lange, Elizabeth Choy, Karie Poon, Tatiana Moreno and Dr. Anupama Singh. Another Rutger researcher involved in the study is Dr. Meghan Arnold.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported in part through funds from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Aging, a Paul F. Glenn Center Fellowship, a Larry L. Hillblom Fellowship, a Taiwan Global Fellowship, a Larry L. Hillblom Fellowship, and a Breakthrough in Gerontology Award from the American Association for Aging Research.

COI: The authors declare no competing interests.

About the Buck Institute for Research on Aging

At the Buck, we aim to end the threat of age-related diseases for this and future generations. We bring together the most capable and passionate scientists from a broad range of disciplines to study mechanisms of aging and to identify therapeutics that slow down aging. Our goal is to increase human health span, or the healthy years of life. Located just north of San Francisco, we are globally recognized as the pioneer and leader in efforts to target aging, the number one risk factor for serious diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, cancer, macular degeneration, heart disease, and diabetes. The Buck wants to help people live better longer. Our success will ultimately change healthcare. Learn more at: https://buckinstitute.org

END

New roles for autophagy genes in cellular waste management and aging

Autophagy genes help extrude protein aggregates from neurons in the nematode C. elegans

2024-01-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The surprisingly resourceful ways bacteria thrive in the human gut

2024-01-04

The gut microbiome is so useful to human digestion and health that it is often called an extra digestive organ. This vast collection of bacteria and other microorganisms in the intestine helps us break down foods and produce nutrients or other metabolites that impact human health in a myriad of ways. New research from the University of Chicago shows that some groups of these microbial helpers are amazingly resourceful too, with a large repertoire of genes that help them generate energy for themselves and potentially influence human health as well.

The paper, published January 4, 2024, in Nature ...

Genomic ‘tweezer’ ushers in a new era of precision in microbiome research

2024-01-04

In a landmark study recently published in the journal Nature Methods, researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have unveiled mEnrich-seq—an innovative method designed to substantially enhance the specificity and efficiency of research into microbiomes, the complex communities of microorganisms that inhabit the human body.

Unlocking the Microbial World with mEnrich-seq

Microbiomes play a crucial role in human health. An imbalance or a decrease in the variety of microbes in our bodies can lead to an increased risk of several diseases. However, in many microbiome applications, the focus is on studying specific ...

Scientists tame chaotic protein fueling 75% of cancers

2024-01-04

Meet MYC, the shapeless protein responsible for making the majority of human cancer cases worse. UC Riverside researchers have found a way to rein it in, offering hope for a new era of treatments.

In healthy cells, MYC helps guide the process of transcription, in which genetic information is converted from DNA into RNA and, eventually, into proteins. “Normally, MYC’s activity is strictly controlled. In cancer cells, it becomes hyper active, and is not regulated properly,” said UCR associate professor of chemistry Min Xue.

“MYC is less like food for cancer cells and more like a steroid ...

Breakthrough in designing complicated all-α protein structures

2024-01-04

A team of researchers has developed an innovative method to design complicated all-α proteins, characterized by their non-uniformly arranged α-helices as seen in hemoglobin. Employing their novel approach, the team successfully created five unique all-α protein structures, each distinguished by their complicated arrangements of α-helices. This capability holds immense potential in designing functional proteins.

This research has been published in the journal Nature Structural and Molecular Biology on January 4, 2024.

Proteins fold into unique three-dimensional structures based on their amino acid sequences, which then dictate their ...

Scientists solve mystery of how predatory bacteria recognizes prey

2024-01-04

A decades-old mystery of how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria are able to recognize and kill other bacteria may have been solved, according to new research.

In a study published today (4th January) in Nature Microbiology, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham have discovered how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria, called Bdellovibrio bacterivorous, produce fibre-like proteins on their surface to ensnare prey.

This discovery may enable scientists to use these predators to target and kill ...

Scientists engineer plant microbiome for the first time to protect crops against disease

2024-01-04

Breakthrough could dramatically cut the use of pesticides and unlock other opportunities to bolster plant health

Scientists have engineered the microbiome of plants for the first time, boosting the prevalence of ‘good’ bacteria that protect the plant from disease.

The findings published in Nature Communications by researchers from the University of Southampton, China and Austria, could substantially reduce the need for environmentally destructive pesticides.

There is growing public awareness about the significance of our microbiome – the myriad of microorganisms that live in and around our bodies, most notably in our guts. Our gut ...

Chiba University is pleased to announce the International Conference: “Humanities In The Age Of Space Exploration”

2024-01-04

Introduction to the Event: As the world witnesses rapid technological advancements and the increasing reality of space travel and habitation, Chiba University is taking the lead in shaping the dialogue on the future of space development and humanity. The upcoming conference will feature distinguished speakers from Chiba University and international institutions, converging to facilitate interdisciplinary discussions. Through diverse lenses encompassing philosophy, ethics, law, political science, and horticulture, the conference aims to gain profound insights, welcoming active ...

US study offers a different explanation why only 36% of psychology studies replicate

2024-01-04

In light of an estimated replication rate of only 36% out of 100 replication attempts conducted by the Open Science Collaboration in 2015 (OSC2015), many believe that experimental psychology suffers from a severe replicability problem.

In their own study, recently published in the open-access peer-reviewed scientific journal Social Psychological Bulletin, Drs Brent M. Wilson and John T. Wixted at the University of California San Diego (USA) suggest that what has since been referred to as a “replication crisis” might not be as bad as it seems.

“No one asks a critical question,” the scientists argue, “if ...

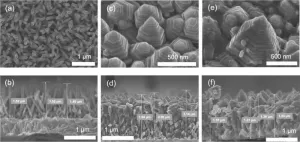

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode

2024-01-04

Overview

A research team consisting of members of the Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute and the Functional Materials Engineering Laboratory at the Toyohashi University of Technology, has developed a novel high-performance photoelectrode by constructing a zinc oxide nanopagoda array with a unique shape on a transparent electrode and applying silver nanoparticles to its surface. The zinc oxide nanopagoda is characterized by having many step structures, as it comprises stacks of differently sized hexagonal prisms. In addition, it exhibits very few crystal defects and excellent electron conductivity. By decorating its surface with silver nanoparticles, the zinc oxide nanopagoda ...

Vitamin discovered in rivers may offer hope for salmon suffering from thiamine deficiency disease

2024-01-04

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University researchers have discovered vitamin B1 produced by microbes in rivers, findings that may offer hope for vitamin-deficient salmon populations.

Findings were published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

The authors say the study in California’s Central Valley represents a novel piece of an important physiological puzzle involving Chinook salmon, a keystone species that holds significant cultural, ecological and economic importance in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Christopher ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

[Press-News.org] New roles for autophagy genes in cellular waste management and agingAutophagy genes help extrude protein aggregates from neurons in the nematode C. elegans