(Press-News.org) How deeply someone can be hypnotized — known as hypnotizability — appears to be a stable trait that changes little throughout adulthood, much like personality and IQ. But now, for the first time, Stanford Medicine researchers have demonstrated a way to temporarily heighten hypnotizablity — potentially allowing more people to access the benefits of hypnosis-based therapy.

In the new study, to be published Jan. 4 in Nature Mental Health, the researchers found that less than two minutes of electrical stimulation targeting a precise area of the brain could boost participants’ hypnotizability for about one hour.

“We know hypnosis is an effective treatment for many different symptoms and disorders, in particular pain,” said Afik Faerman, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in psychiatry and lead author of the study. “But we also know that not everyone benefits equally from hypnosis.”

Focused attention

Approximately two-thirds of adults are at least somewhat hypnotizable, and 15% are considered highly hypnotizable, meaning they score 9 or 10 on a standard 10-point measure of hypnotizability.

“Hypnosis is a state of highly focused attention, and higher hypnotizability improves the odds of your doing better with techniques using hypnosis,” said David Spiegel, MD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and a senior author of the study.

Spiegel, the Jack, Lulu, and Sam Willson Professor in Medicine, has devoted decades to studying hypnotherapy and using it to help patients control pain, lower stress, stop smoking and more. Several years ago, Spiegel led a team that used brain imaging to uncover the neurobiological basis of the practice. They found that highly hypnotizable people had stronger functional connectivity between the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is involved in information processing and decision making; and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, involved in detecting stimuli.

“It made sense that people who naturally coordinate activity between these two regions would be able to concentrate more intently,” Spiegel said. “It’s because you’re coordinating what you are focusing on with the system that distracts you.”

Shifting a stable trait

With these insights, Spiegel teamed up with Nolan Williams, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, who has pioneered non-invasive neurostimulation techniques to treat conditions such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and suicidal ideation.

The hope was that neurostimulation could alter even a stable trait like hypnotizability.

In the new study, the researchers recruited 80 participants with fibromyalgia, a chronic pain condition that can be treated with hypnotherapy. They excluded those who were already highly hypnotizable.

Half of the participants received transcranial magnetic stimulation, in which paddles applied to the scalp deliver electrical pulses to the brain. Specifically, they received two 46-second applications that delivered 800 pulses of electricity to a precise location in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The exact locations depended on the unique structure and activity of each person’s brain.

“A novel aspect of this trial is that we used the person’s own brain networks, based on brain imaging, to target the right spot,” said Williams, also a senior author of the study.

The other half of participants received a sham treatment with the same look and feel, but without electrical stimulation.

Hypnotizability was assessed by clinicians immediately before and after the treatments, with neither patients nor clinicians knowing who was in which group.

The researchers found that participants who received the neurostimulation showed a statistically significant increase in hypnotizability, scoring roughly one point higher. The sham group experienced no effect.

When the participants were assessed again one hour later, the effect had worn off and there was no longer a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

“We were pleasantly surprised that we were able to, with 92 seconds of stimulation, change a stable brain trait that people have been trying to change for 100 years,” Williams said. “We finally cracked the code on how to do it.”

The researchers plan to test whether different dosages of neurostimulation could enhance hypnotizability even more.

“It’s unusual to be able to change hypnotizability,” Spiegel said. A study of Stanford University students that began in the 1950s, for example, found that the trait remained relatively consistent when the students were tested 25 years later, as consistent as IQ over that time period. Recent research by Spiegel’s lab also suggests that hypnotizability may have a genetic basis.

Bigger implications

Clinically, a transient bump in hypnotizability may be enough to allow more people living with chronic pain to choose hypnosis as an alternative to long-term opioid use. Spiegel will follow up with the study participants to see how they fare in hypnotherapy.

The new results could have implications beyond hypnosis. Faerman noted that neurostimulation may be able to temporarily shift other stable traits or enhance people’s response to other forms of psychotherapy.

“As a clinical psychologist, my personal vision is that, in the future, patients come in, they go into a quick, non-invasive brain stimulation session, then they go in to see their psychologist,” he said. “Their benefit from treatment could be much higher.”

The study was supported by funding from the National Institute of Health (grant R33AT009305-03).

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END

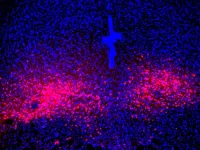

LA JOLLA (January 4, 2024)—Overwhelming fear, sweaty palms, shortness of breath, rapid heart rate—these are the symptoms of a panic attack, which people with panic disorder have frequently and unexpectedly. Creating a map of the regions, neurons, and connections in the brain that mediate these panic attacks can provide guidance for developing more effective panic disorder therapeutics.

Now, Salk researchers have begun to construct that map by discovering a brain circuit that mediates panic ...

New study reveals striking similarities in synaptic abnormalities and behavioral patterns between male and female mouse models of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The study challenges the traditional focus on male subjects in ASD research and highlights the critical importance of including both sexes in investigations. This finding urges a pivotal shift in the scientific community's approach to understanding and addressing ASD, emphasizing the necessity of considering both males and females to comprehensively ...

Researchers from Amsterdam UMC and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU) have discovered that the persistent fatigue in patients with long-COVID has a biological cause, namely mitochondria in muscle cells that produce less energy than in healthy patients. The results of the study were published today in Nature Communications.

"We're seeing clear changes in the muscles in these patients," says Michèle van Vugt, Professor of Internal Medicine at Amsterdam UMC.

25 long-COVID patients and 21 healthy ...

Autophagy, which declines with age, may hold more mysteries than researchers previously suspected. In the January 4th issue of Nature Aging, it was noted that scientists from the Buck Institute, Sanford Burnham Prebys and Rutgers University have uncovered possible novel functions for various autophagy genes, which may control different forms of disposal including misfolded proteins—and ultimately affect aging.

“While this is very basic research, this work is a reminder that it is critical for us to understand whether we have the whole story about the different genes that have been related to aging or age-related diseases,” said Professor ...

The gut microbiome is so useful to human digestion and health that it is often called an extra digestive organ. This vast collection of bacteria and other microorganisms in the intestine helps us break down foods and produce nutrients or other metabolites that impact human health in a myriad of ways. New research from the University of Chicago shows that some groups of these microbial helpers are amazingly resourceful too, with a large repertoire of genes that help them generate energy for themselves and potentially influence human health as well.

The paper, published January 4, 2024, in Nature ...

In a landmark study recently published in the journal Nature Methods, researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have unveiled mEnrich-seq—an innovative method designed to substantially enhance the specificity and efficiency of research into microbiomes, the complex communities of microorganisms that inhabit the human body.

Unlocking the Microbial World with mEnrich-seq

Microbiomes play a crucial role in human health. An imbalance or a decrease in the variety of microbes in our bodies can lead to an increased risk of several diseases. However, in many microbiome applications, the focus is on studying specific ...

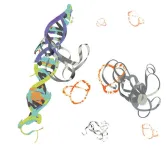

Meet MYC, the shapeless protein responsible for making the majority of human cancer cases worse. UC Riverside researchers have found a way to rein it in, offering hope for a new era of treatments.

In healthy cells, MYC helps guide the process of transcription, in which genetic information is converted from DNA into RNA and, eventually, into proteins. “Normally, MYC’s activity is strictly controlled. In cancer cells, it becomes hyper active, and is not regulated properly,” said UCR associate professor of chemistry Min Xue.

“MYC is less like food for cancer cells and more like a steroid ...

A team of researchers has developed an innovative method to design complicated all-α proteins, characterized by their non-uniformly arranged α-helices as seen in hemoglobin. Employing their novel approach, the team successfully created five unique all-α protein structures, each distinguished by their complicated arrangements of α-helices. This capability holds immense potential in designing functional proteins.

This research has been published in the journal Nature Structural and Molecular Biology on January 4, 2024.

Proteins fold into unique three-dimensional structures based on their amino acid sequences, which then dictate their ...

A decades-old mystery of how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria are able to recognize and kill other bacteria may have been solved, according to new research.

In a study published today (4th January) in Nature Microbiology, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham have discovered how natural antimicrobial predatory bacteria, called Bdellovibrio bacterivorous, produce fibre-like proteins on their surface to ensnare prey.

This discovery may enable scientists to use these predators to target and kill ...

Breakthrough could dramatically cut the use of pesticides and unlock other opportunities to bolster plant health

Scientists have engineered the microbiome of plants for the first time, boosting the prevalence of ‘good’ bacteria that protect the plant from disease.

The findings published in Nature Communications by researchers from the University of Southampton, China and Austria, could substantially reduce the need for environmentally destructive pesticides.

There is growing public awareness about the significance of our microbiome – the myriad of microorganisms that live in and around our bodies, most notably in our guts. Our gut ...