Over the past decades, scientists have made substantial progress unveiling the underlying mechanisms behind many psychiatric disorders. Every year, new genetic mutations or protein dysregulations are identified as potential culprits for the symptoms, and sometimes even the root causes of complex neurological diseases, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s.

Despite these efforts, the precise roles of several proteins involved in brain function remain obscure. Such is the case for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 (IDO2), an enzyme expressed in the brain and metabolized by the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway (TKP). Changes in the metabolites of this pathway have already been linked to many psychiatric disorders, and genetically modified mice have been invaluable tools in such studies. However, the detailed functions of IDO2 in the brain are not known.

Against this backdrop, a research team led by Associate Professor Yasuko Yamamoto, along with colleagues Masaki Ishikawa and Kuniaki Saito, all from Fujita Health University, Japan, conducted an in-depth study on how and why IDO2, and its lack thereof, affects behavioral patterns in mice. Their paper was published in The FEBS Journal online on November 30, 2023.

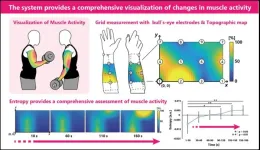

First, the researchers performed behavioral experiments involving normal and genetically modified mice which lacked the IDO2 gene also referred to as IDO2 knock out (KO) mice. These tests revealed many behavioral abnormalities that were representative of ASD. For example, these mice had difficulty acclimatizing to a new environment, exhibiting repetitive grooming and stereotyped behavior. Moreover, these mice spent less time burying marbles, which indicates limited interest in their surroundings. Finally, experiments on social interactions revealed that the KO mice had trouble learning behaviors from other mice.

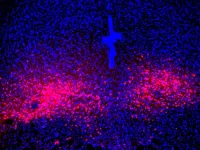

Following these tests, the team sought to clarify the biochemical effects of IDO2 in the brain to explain the abnormal behaviors observed. They first found that the deletion of IDO2 led to alterations in the levels of tryptophan metabolites as well as in the TKP. Most importantly, they found that IDO2 KO mice exhibited significant changes in the balance between dopamine release and uptake, especially in the striatum and amygdala regions of the brain. This imbalance led to the downregulation of many molecules that are downstream in the dopamine D1 receptor signaling pathway, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is important for the formation of new neurons (brain cells) and the ability of the brain to adapt to new stimuli (neuroplasticity).

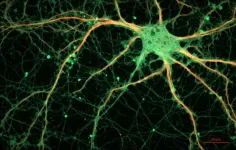

Through morphological analysis of neurons in the striatum, the researchers observed that these alterations in dopamine signaling caused IDO2 KO mice to exhibit a significantly higher density of immature dendritic spines. They also observed important changes in populations of cells known as microglia. “Microglia are resident immune cells that exist in the central nervous system (CNS) since the early embryonic stage when the nerves and cerebrovascular systems are being formed. During the development of the CNS, microglia regulate the pruning of excess synapses,” explains Assoc. Prof. Yamamoto.

It turns out that, in IDO2 KO mice, microglia in the striatum tend to convert from a ‘surveillant’ type to an ‘ameboid’ type. Since only surveillant microglia oversee the removal of excess neural synapses and controlling synaptic transmission, these synaptic abnormalities plus the dysregulation of BDNF could be responsible for the ASD-like behaviors observed in KO mice. Moreover, chemically restoring the production of IDO2 in genetically modified mice led to behaviors similar to those of normal mice.

Finally, through the genetic analysis of 309 clinical brain samples from ASD patients, the team found a case of a 16-year-old girl who had a mutation in the IDO2 gene. It is possible that her symptoms could be at least partially explained by alterations in IDO2.

Taken together, the findings of this study could serve as a steppingstone to understand the genetic and biochemical nature of certain psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders. “This work provides valuable insights into the pathophysiology associated with IDO2, although further research should be performed to clarify the underlying mechanisms in more detail,” concludes Assoc. Prof. Yamamoto, with eyes on the future.

Let us hope more studies on IDO2 and tryptophan-metabolizing enzymes lead to a better understanding of how autism develops and manifests.

***

Reference

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.17019

About Fujita Health University

Fujita Health University is a private university situated in Toyoake, Aichi, Japan. It was founded in 1964 and houses one of the largest teaching university hospitals in Japan in terms of the number of beds. With over 900 faculty members, the university is committed to providing various academic opportunities to students internationally. Fujita Health University has been ranked eighth among all universities and second among all private universities in Japan in the 2020 Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings. THE University Impact Rankings 2019 visualized university initiatives for sustainable development goals (SDGs). For the “good health and well-being” SDG, Fujita Health University was ranked second among all universities and number one among private universities in Japan. The university became the first Japanese university to host the "THE Asia Universities Summit" in June 2021. The university’s founding philosophy is “Our creativity for the people (DOKUSOU-ICHIRI),” which reflects the belief that, as with the university’s alumni and alumnae, current students also unlock their future by leveraging their creativity.

Website: https://www.fujita-hu.ac.jp/en/index.html

About Associate Professor Yasuko Yamamoto from Fujita Health University

Yasuko Yamamoto received a Ph.D. in Health Sciences from the Graduate School of Medicine at Osaka University. After working at the Kagawa Prefectural College of Health Sciences for over 6 years and at Kyoto University for a decade, she joined Fujita Health University in 2016, where she currently serves as Associate Professor. She specializes in the pathobiochemistry of diverse diseases, such as neuropsychiatric disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and COVID-19. She has published over 85 papers on these topics.

Funding information

This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 19K07490, 18K19761, and 17H04252 and a Research Grant from the Smoking Research Foundation.

END