(Press-News.org) Press release – Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology

EMBARGO: 8 JANUARY 2024 AT 11:00 AM ET (US)

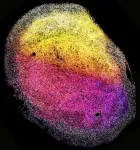

Scientists have developed 3D mini-organs from human fetal brain tissue that self-organize in vitro. These lab-grown organoids open up a brand-new way of studying how the brain develops. They also offer a valuable means to study the development and treatment of diseases related to brain development, including brain tumors.

Scientists use different ways to model the biology of healthy tissue and disease in the lab. These include cell lines, laboratory animals and, since a few years, 3D mini-organs. These so-called organoids have characteristics and a level of complexity that allows scientists to closely model the functions of an organ in the lab. Organoids can be formed directly from cells of a tissue. Scientists can also ‘guide’ stem cells – found in embryos or in some adult tissues – to develop into the organ they aim to study.

Until now, brain organoids were grown in the lab by coaxing embryonic or pluripotent stem cells to grow into structures representing different areas of the brain. Using a specific cocktail of molecules, they would try to mimic the natural development of the brain – with the ‘recipe’ for each cocktail taking a lot of research to develop.

Now, scientists at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology and the Hubrecht Institute, both based in Utrecht, the Netherlands, developed brain organoids directly from human fetal brain tissue. The study was published in the prestigious journal Cell today (Monday), and was part-funded by the Dutch Research Council.

The researchers, led by Dr. Delilah Hendriks, Prof. Dr. Hans Clevers and Dr. Benedetta Artegiani, were surprised to find that using small pieces of fetal brain tissue rather than individual cells was vital in growing mini-brains. To grow other mini-organs such as gut, scientists normally break down the original tissue to single cells. Instead working with small pieces of fetal brain tissue, the team found that these pieces could self-organize into organoids.

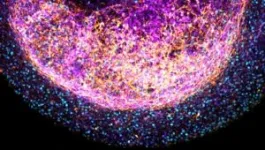

The brain organoids were roughly the size of a grain of rice. The tissue’s 3D make-up was complex, and it contained a number of different types of brain cells. Importantly, the brain organoids contained many so-called outer radial glia – a cell type found in humans and our evolutionary ancestors. This underlines the organoids’ close similarity to – and use in studying – the human brain.

The whole pieces of brain tissue also produced proteins that make up extracellular matrix – a kind of ‘scaffolding’ around cells. The team believes these proteins could be the reason why the pieces of brain tissue were able to self-organize into 3D brain structures. The presence of extracellular matrix in the organoids will allow further study of the environment of brain cells, and what happens when this goes wrong.

The researchers found that the tissue-derived organoids kept various characteristics of the specific region of the brain from which they were derived. They responded to signaling molecules known to play an important role in brain development. This finding suggests that the tissue-derived organoids could play an important role in untangling the complex network of molecules involved in directing the development of the brain.

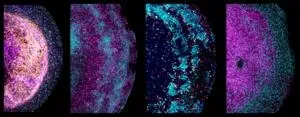

Given the ability of the tissue-derived organoids to quickly expand, the team next investigated their potential in modeling brain cancer. The researchers used gene-editing technique CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce faults in the well-known cancer gene TP53 in a small number of cells in the organoids. After three months, the cells with defective TP53 had completely overtaken the healthy cells in the organoid – meaning they had acquired a growth advantage, a typical feature of cancer cells.

They then used CRISPR-Cas9 to switch off three genes linked to the brain tumor, glioblastoma: TP53, PTEN and NF1. The researchers also used these mutant organoids to look at their response to existing cancer drugs. These experiments showed the organoids’ potential for cancer drug research to link certain drugs to specific gene mutations.

The tissue-derived organoids continued to grow in a dish for more than six months. Importantly, the scientists could multiply them, allowing them to grow many similar organoids from one tissue sample. The mini-tumors with the glioblastoma gene changes – were also capable of multiplying, keeping the same mix of mutations. This feature means scientists can carry out repeat experiments with the tissue-derived organoids, increasing the reliability of their findings.

Next, the researchers aim to further explore the potential of their new tissue-derived brain organoids. They also plan to continue their work with bioethicists – who were already involved in shaping this research – to guide the future development and applications of the new brain organoids.

Dr. Benedetta Artegiani, research group leader at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology who co-led the research, says:

‘Brain organoids from fetal tissue are an invaluable new tool to study human brain development. We can now more easily study how the developing brain expands, and look at the role of different cell types and their environment.

‘Our new, tissue-derived brain model allows us to gain a better understanding of how the developing brain regulates the identity of cells. It could also help understand how mistakes in that process can lead to neurodevelopmental diseases such as microcephaly, as well as other diseases that can stem from derailed development, including childhood brain cancer.’

Dr. Delilah Hendriks, affiliated group leader at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology, postdoctoral researcher at the Hubrecht Institute and Oncode Investigator, who co-led the research, says:

‘These new fetal tissue-derived organoids can offer novel insights into what shapes the different regions of the brain, and what creates cellular diversity. Our organoids are an important addition to the brain organoid field, that can complement the existing organoids made from pluripotent stem cells. We hope to learn from both models to decode the complexity of the human brain.

‘Being able to keep growing and using the brain organoids from fetal tissue also means that we can learn as much as possible from such precious material. We’re excited to explore the use of these novel tissue organoids for new discoveries about the human brain.’

Prof. dr. Hans Clevers, pioneer in organoid research and former research group leader at the Hubrecht Institute and the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology and Oncode Investigator, co-led the research. He says:

‘With our study, we’re making an important contribution to the organoid and brain research fields. Since we developed the first human gut organoids in 2011, it’s been great to see that the technology has really taken off. Organoids have since been developed for almost all tissues in the human body, both healthy and diseased – including an increasing number of childhood tumors.

‘Until now, we were able to derive organoids from most human organs, but not from the brain – it’s really exciting that we’ve now been able to jump that hurdle as well.’

The study was performed in collaboration with Leiden University Medical Center, Utrecht University, Maastricht University, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and National University of Singapore.

- ENDS -

Notes to editors

The human fetal tissue was derived from healthy abortion material, between gestational weeks 12-15, from fully anonymous donors. The anonymous women donated the tissue voluntarily and upon informed consent. They were informed that the material would be used for research purposes only, and that the research included the understanding of how organs normally develop, including the possibility to grow cells derived from the donated material.

About the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology

When a child is seriously ill from cancer, only one thing matters: a cure.

Every year, 600 children in the Netherlands are diagnosed with cancer. Sadly, one in four of these children dies. That is why in the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology, we work together with passion and without limits every day to improve the survival rate and quality of life of children with cancer. Now, and in the long term. Because children have their whole lives ahead of them.

The Princess Máxima Center is no ordinary hospital, but a research hospital. All children with cancer in the Netherlands are treated here, and it’s where all research into childhood cancer in the country takes place. This makes the Princess Máxima Center the largest pediatric cancer center in Europe. More than 900 healthcare professionals and 450 scientists work closely with Dutch and international hospitals to find better treatments and new perspectives for a cure.

In this way, we offer children today the best possible care, and we take important steps to improve survival for children who cannot not yet be cured.

END

Novel tissue-derived brain organoids could revolutionize brain research

2024-01-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 is less resistant to vaccine, but may be a problem in the lung

2024-01-08

COLUMBUS, Ohio – New research shows that the recently emerged BA.2.86 omicron subvariant of the virus that causes COVID-19 can be neutralized by bivalent mRNA vaccine-induced antibodies in the blood, which explains why this variant did not cause a widespread surge as previously feared.

However, the study in cell cultures showed this SARS-CoV-2 variant can infect human cells that line the lower lung and engage in virus-host cell membrane fusion more efficiently, two features linked to severe disease symptoms.

The study is published today (Jan. 8, 2024) in the journal Cell.

The BA.2.86 variant of omicron is the ancestor of the currently dominating JN.1 and has about ...

Sibling death in childhood and early adulthood and risk of early-onset cardiovascular disease

2024-01-08

About The Study: In this study of more than 2 million individuals born in Denmark, sibling death in childhood and early adulthood was associated with increased risks of overall and most type-specific early-onset cardiovascular diseases, with the strength of associations varying by cause of death and age difference between sibling pairs. The findings highlight the need for extra attention and support to the bereaved siblings to reduce cardiovascular disease risk later in life.

Authors: Guoyou Qin, Ph.D., and Yongfu Yu, Ph.D., ...

Early-life digital media experiences and development of atypical sensory processing

2024-01-08

About The Study: Early-life digital media exposure was associated with atypical sensory processing outcomes in multiple domains in this study that included 1,471 children. These findings suggest that digital media exposure might be a potential risk factor for the development of atypical sensory profiles. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between screen time and specific sensory-related developmental and behavioral outcomes, and whether minimizing early-life exposure can improve subsequent sensory-related outcomes.

Authors: Karen F. Heffler, M.D., of the Drexel University ...

Diagnostic errors in hospitalized adults who died or were transferred to intensive care

2024-01-08

About The Study: Diagnostic errors in hospitalized adults who died or were transferred to the intensive care unit were common and associated with patient harm in this analysis of 2,428 patient records at 29 hospitals. Problems with choosing and interpreting tests and the processes involved with clinician assessment are high-priority areas for improvement efforts.

Authors: Andrew D. Auerbach, M.D., M.P.H., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

Putting your toddler in front of the TV? You might hurt their ability to process the world around them, new data suggests

2024-01-08

Babies and toddlers exposed to television or video viewing may be more likely to exhibit atypical sensory behaviors, such as being disengaged and disinterested in activities, seeking more intense stimulation in an environment, or being overwhelmed by sensations like loud sounds or bright lights, according to data from researchers at Drexel’s College of Medicine published today in the journal JAMA Pediatrics.

According to the researchers, children exposed to greater TV viewing by their second birthday were more likely to develop atypical sensory processing behaviors, such as “sensation seeking” and “sensation ...

Closing in on triple-negative breast cancer

2024-01-08

Cedars-Sinai Cancer investigators have analyzed the cells within triple-negative breast cancer tumors before and after radiation therapy with immunotherapy, identifying three patient groups with different responses to the treatment. Their study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Cancer Cell, found that for some patients with this difficult-to-treat cancer, radiation therapy plus immunotherapy could yield the best tumor-fighting immune response prior to surgery.

“Our most important finding was identifying these three different patient groups,” said Simon Knott, PhD, co-director of the Applied Genomics Shared Resource at ...

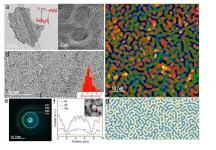

Revolutionizing stable and efficient catalysts with Turing structures for hydrogen production

2024-01-08

Hydrogen energy has emerged as a promising alternative to fossil fuels, offering a clean and sustainable energy source. However, the development of low-cost and efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction remains a crucial challenge. A research team led by scientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has recently developed a novel strategy to engineer stable and efficient ultrathin nanosheet catalysts by forming Turing structures with multiple nanotwin crystals. This innovative discovery paves the way for enhanced catalyst performance for green hydrogen production.

Producing hydrogen through the process of ...

Widespread population collapse of African Raptors

2024-01-08

An international team of researchers has found that Africa’s birds of prey are facing an extinction crisis.

The report, co-led by researchers from the School of Biology at the University of St Andrews and The Peregrine Fund, and published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution (4 January 2024), warns of declines among nearly 90% of 42 species examined, and suggests that more than two-thirds may qualify as globally threatened.

Led by Dr Phil Shaw from St Andrews and Dr Darcy Ogada of The Peregrine ...

Certain combinations of gut bacteria protect stem cell transplantation patients from dangerous immune reactions

2024-01-08

After stem cell transplantation, the donated immune cells sometimes attack the patients' bodies. This is known as graft versus host disease or GvHD. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Universitätsklinikum Regensburg (UKR) have shown that GvHD is much less common when certain microbes are present in the gut. In the future, it may be possible to deliberately bring about this protective composition of the microbiome.

Stem cell transplantation can save the lives of patients suffering ...

PKU scientists and collaborators invent ultrathin optical crystal for next-generation laser tech

2024-01-08

BEIJING, Dec. 19 (Xinhua) -- A team of Chinese researchers used a novel theory to invent a new type of ultrathin optical crystal with high energy efficiency, laying the foundation for next-generation laser technology.

Prof. Wang Enge from the School of Physics, Peking University, recently told Xinhua that the Twist Boron Nitride (TBN) made by the team, with a micron-level thickness, is the thinnest optical crystal currently known in the world. Compared with traditional crystals of the same thickness, its energy efficiency is raised by 100 to 10,000 times.

Wang, also an ...