(Press-News.org) RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Size does not matter. Certainly not when it comes to tiny worms securing the attention of biologists. One such biologist, Morris F. Maduro at the University of California, Riverside, has just been awarded a grant of nearly $1.3 million from the National Science Foundation, or NSF, to study a worm (or nematode) about a millimeter in length.

The research project will focus on the gut of Pristionchus pacificus. Like most nematodes, P. pacificus develops quickly, its growth from embryo to adult taking just four days. It is a complete animal, with a nervous system, skin, intestine, and muscles. Nematodes of the genus Pristionchus are a distant relative of the well-studied species Caenorhabditis elegans, used by biologists as a model organism to study animal development and behavior.

Funded for four years, the research project will focus on changes in the gene network that specify the early intestinal precursor cells in nematodes like P. pacificus. Gene networks describe how genes turn each other on and off. Precursor cells are stem cells that can differentiate — or specialize — into only one cell type.

“During embryonic development, gene networks cause cells to develop along pathways of differentiation, resulting in cells becoming specialized in their function,” said Maduro, a professor of molecular, cell and systems biology who has studied nematodes for more than two decades. “Changes in such networks occur over evolutionary time and in human disease. For more than 25 years, gut specification was studied in only a single species, C. elegans, and its close relatives. The NSF grant will allow us to extend our work into the genus Pristionchus.”

P. pacificus is usually found in association with a species of scarab beetle, while C. elegans is free-living and usually found on rotting fruit. P. pacificus has some adaptations, such as a mouth with a little tooth for eating the corpses of dead beetles. As a result, P. pacificus can attack other nematodes and is more predatory than C. elegans. C. elegans tends to eat mostly bacteria and fungi.

“Pristionchus embryos look a like those of C. elegans,” Maduro said. “But even when the phenotype, the outward form of the animal, doesn’t change, the genes behind the scenes can still change. This phenomenon is called developmental system drift, paralleling the term genetic drift. Entire sets of genes can change while their overall function does not. In other words, the endpoint, whether it’s C. elegans or P. pacificus or another nematode species, still looks like a nematode. This means Pristionchus makes its gut in a different way than C. elegans. This idea that genes change when the phenotype looks the same among species is probably quite widespread.”

Eric S. Haag, a professor of biology at the University of Maryland who will not be participating in the research project, said he is excited to learn more about Maduro’s work.

“Biologists have long sought to understand how new features of animal bodies get encoded by new genomic instructions. But we now know that even the genes that construct ancient traits still undergo evolutionary changes,” Haag said. “Dr. Maduro’s work uses a very manipulable type of nematode to explore this paradoxical fact. Within a group of worms with very similar digestive systems, some species have re-invented the genetic circuits that control their development. It’s so surprising, and I can’t wait to learn about what they find.”

Maduro explained that gene network changes can occur due to mutations or infection and can lead to diseases such as cancer.

“Nematodes are a powerful model system for us to study how gene networks can change, because we can get answers inexpensively and on a short time scale,” he said. “By comparing Pristionchus and C. elegans, we hope to learn fundamental principles about how gene networks can become more complex.”

The project will use a combination of bioinformatic and genetics methods to understand how the simple embryonic gene network in an ancestral Pristionchus species underwent expansion over evolutionary time to form a more complex network.

“Two technologies have allowed researchers to address the explosion of this and other evolutionary questions we see today,” Maduro said. “They are (a) rapid genome sequencing at low cost and (b) the ability to use CRISPR to knock out genes in the genome at low cost and high efficiency.”

Maduro added that nematode species can be found in almost every ecological niche on Earth.

“There are maybe a million different species,” he said. “We can only study a small number of them. Pristionchus garnered scientific interest only about 25 years ago and research took off in earnest in the past decade when CRISPR became available to simplify gene editing. P. pacificus has three genes that specify the gut, but other related species have fewer genes. We have an opportunity to study the stepwise evolution of how this network got bigger and more complicated.”

Preliminary work in Maduro’s lab identified two of these three expanded genes in Pristionchus. When the gene pair was deleted, the gut disappeared in about half of the worms.

“We now need to delete that third gene to make sure we know that’s the only other gene that leads to gut specification,” Maduro said. “This grant will help us do that.”

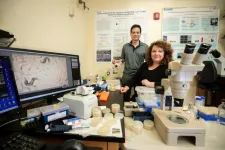

The project will provide teaching and training opportunities for graduate and undergraduate students, including through a freshman laboratory course in nematode genetics, bioinformatics, microscopy, and molecular biology. Four undergraduate students will receive summer support for each year of the grant to work on projects related to Pristionchus. The grant will support up to two graduate students. Maduro will be assisted in the research by his wife, Gina Broitman-Maduro, an associate specialist in his lab. The start date of the grant is January 15, 2024.

The University of California, Riverside is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment is more than 26,000 students. The campus opened a medical school in 2013 and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Center. The campus has an annual impact of more than $2.7 billion on the U.S. economy. To learn more, visit www.ucr.edu.

END

The early bird (or scientist) gets the worm

UC Riverside research on nematodes secures $1.3M NSF funding

2024-01-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

News media trigger conflict for romantic couples with differing political views

2024-01-12

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — By one estimate, as many as 30% of people in the U.S. are in romantic relationships with partners who do not share their political views. In today’s hyperpartisan climate, where Democrats and Republicans have difficulty talking to each other and their views are polarized about media outlets’ credibility, how do couples with differing political perspectives decide which media to follow? And how do these decisions affect their discussions on political issues and their relationship ...

Earth-sized planet discovered in ‘our solar backyard’

2024-01-12

MADISON — A team of astronomers have discovered a planet closer and younger than any other Earth-sized world yet identified. It’s a remarkably hot world whose proximity to our own planet and to a star like our sun mark it as a unique opportunity to study how planets evolve.

The new planet was described in a new study published this week by The Astronomical Journal. Melinda Soares-Furtado, a NASA Hubble Fellow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who will begin work as an astronomy professor at the university in the fall, and recent UW–Madison graduate Benjamin Capistrant, now a graduate student at the University of Florida, co-led the study with co-authors from ...

NASA analysis confirms 2023 as warmest year on record

2024-01-12

Earth’s average surface temperature in 2023 was the warmest on record, according to an analysis by NASA. Global temperatures last year were around 2.1 degrees Fahrenheit (1.2 degrees Celsius) above the average for NASA’s baseline period (1951-1980), scientists from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in New York reported.

“NASA and NOAA’s global temperature report confirms what billions of people around the world experienced last year; we are facing a climate ...

Incontinence could point to future disability

2024-01-12

If you are one of the 30% to 50% of women experiencing urinary incontinence, new research suggests that it could turn into a bigger health issue.

Having more frequent urinary incontinence and leakage amounts is associated with higher odds of disability, according to RUSH researchers in a study published in the January issue of Menopause.

“Often symptoms from urinary incontinence are ignored until they become bothersome or limit physical or social activities,” said Sheila Dugan, MD, chair of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at RUSH. “Because this study suggests that urinary incontinence is associated with disability, ...

Core-shell ‘chemical looping’ boosts efficiency of greener approach to ethylene production

2024-01-12

Ethylene is sometimes called the most important chemical in the petrochemical industry because it serves as the feedstock for a huge range of everyday products. It’s used in the production of antifreeze, vinyl, synthetic rubber, foam insulation, and plastics of all kinds.

Currently, ethylene is produced through an energy- and resource-intensive process called steam cracking, where extremes of temperature and pressure produce ethylene from crude oil in the presence of steam—and in the process, emit tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Another way ...

Targeting Microbiota 2024: Shaping the future of medicine – International leaders unite at the 11th World Congress

2024-01-12

The International Society of Microbiota (ISM) is pleased to announce its 11th World Congress, Targeting Microbiota 2024. This congress is scheduled to take place on October 17-18 in Malta, and will convene international leading experts, researchers, and professionals to explore and discuss the latest advancements in the field of microbiota. Under the new presidency of Maria Cecilia Giron, University of Padova, we anticipate a transformative era, propelling the ISM to new heights in microbiota research.

Thorough Investigation through Specialized Tracks

Recent Advances & Challenges in Microbiota

Microbiota-Host Cross-Talk and Signaling

Metabolomics: Innovations ...

How should boards handle visionary CEOs?

2024-01-12

AUSTIN, Texas — The recent firing and rapid rehiring of Sam Altman, the co-founder and CEO of ChatGPT creator OpenAI, illustrates the delicate dance between visionary CEOs and the boards who oversee them.

Some CEOs — often founders — are fueled by strong convictions about the strategic direction their companies should take. But their boards sometimes don’t share their visions.

When that happens, what is the board’s role in governance? Should it monitor or advise the CEO? Should it back off and approve the CEO’s strategy?

The answer depends on how deeply the CEO is invested in the strategy, says Volker Laux, professor of accounting at Texas ...

Drinkable, carbon monoxide-infused foam enhances effectiveness of experimental cancer therapy

2024-01-12

Did smokers do better than non-smokers in a clinical trial for an experimental cancer treatment? That was the intriguing question that led University of Iowa researchers and their colleagues to develop a drinkable, carbon monoxide-infused foam that boosted the effectiveness of the therapy, known as autophagy inhibition, in mice and human cells. The findings were recently published in the journal Advanced Science.

Looking for ways to exploit biological differences between cancer cells and healthy cells ...

Light-matter interaction: broken symmetry drives polaritons

2024-01-12

An international team of scientists provide an overview of the latest research on light-matter interactions. A team of scientists from the Fritz Haber Institute, the City University of New York and the Universidad de Oviedo has published a comprehensive review article in the scientific journal Nature Reviews Materials. In this article, they provide an overview of the latest research on polaritons, tiny particles that arise when light and material interact in a special way.

In recent years, researchers worldwide have discovered that there are different types of polaritons. Some of them can trap light in a very small space, about the size of a nanometer. That's ...

Neuroscientists identify 'chemical imprint of desire'

2024-01-12

Hop in the car to meet your lover for dinner and a flood of dopamine— the same hormone underlying cravings for sugar, nicotine and cocaine — likely infuses your brain’s reward center, motivating you to brave the traffic to keep that unique bond alive. But if that dinner is with a mere work acquaintance, that flood might look more like a trickle, suggests new research by University of Colorado Boulder neuroscientists.

“What we have found, essentially, is a biological signature of desire that helps us explain why we want to be with some people more than other people,” said senior author Zoe Donaldson, associate professor ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study finds Earth may have twice as many vertebrate species as previously thought

NYU Langone orthopedic surgeons present latest clinical findings and research at AAOS 2026

New journal highlights how artificial intelligence can help solve global environmental crises

Study identifies three diverging global AI pathways shaping the future of technology and governance

Machine learning advances non targeted detection of environmental pollutants

ACP advises all adults 75 or older get a protein subunit RSV vaccine

New study finds earliest evidence of big land predators hunting plant-eaters

Newer groundwater associated with higher risk of Parkinson’s disease

New study identifies growth hormone receptor as possible target to improve lung cancer treatment

Routine helps children adjust to school, but harsh parenting may undo benefits

IEEE honors Pitt’s Fang Peng with medal in power engineering

SwRI and the NPSS Consortium release new version of NPSS® software with improved functionality

Study identifies molecular cause of taste loss after COVID

Accounting for soil saturation enhances atmospheric river flood warnings

The research that got sick veterans treatment

Study finds that on-demand wage access boosts savings and financial engagement for low-wage workers

Antarctica has lost 10 times the size of Greater Los Angeles in ice over 30 years

Scared of spiders? The real horror story is a world without them

New study moves nanomedicine one step closer to better and safer drug delivery

Illinois team tests the costs, benefits of agrivoltaics across the Midwest

Highly stable self-rectifying memristor arrays: Enabling reliable neuromorphic computing via multi-state regulation

Composite superionic electrolytes for pressure-less solid-state batteries achieved by continuously perpendicularly aligned 2D pathways

Exploring why some people may prefer alcohol over other rewards

How expectations about artificial sweeteners may affect their taste

Ultrasound AI receives FDA De Novo clearance for delivery date AI technology

Amino acid residue-driven nanoparticle targeting of protein cavities beyond size complementarity

New AI algorithm enables scientific monitoring of "blue tears"

Insufficient sleep among US adolescents across behavioral risk groups

Long COVID and recovery among US adults

Trends in poverty and birth outcomes in the US

[Press-News.org] The early bird (or scientist) gets the wormUC Riverside research on nematodes secures $1.3M NSF funding