(Press-News.org) When researchers want to study how COVID makes us sick, or what diseases such as Alzheimer's do to the body, one approach is to look at what's happening inside individual cells.

Researchers sometimes grow the cells in a 3D scaffold called a "hydrogel." This network of proteins or molecules mimics the environment the cells would live in inside the body.

New research led by the University of Washington demonstrates a new class of hydrogels that can form not just outside cells, but also inside of them. The team created these hydrogels from protein building blocks designed using a computer to form a specific structure. These hydrogels exhibited similar mechanical properties both inside and outside of cells, providing researchers with a new tool to group proteins together inside of cells.

The team published these results Jan. 30 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"In the past 10 years, there's been a shift in the world of cell biology," said co-senior author Cole DeForest, a UW associate professor of chemical engineering and of bioengineering. "Classically, folks have attributed much of the cell’s interior organization to membrane-bound organelles, such as mitochondria or the nucleus. But now scientists are realizing that the cell actually has other ways to locally concentrate certain molecules or proteins without using membranes, for example, by protein-protein interactions. This concentrating allows the cell to turn on or off specific functions that can be helpful or ultimately lead to disease."

DeForest continued: "What I think is pretty exciting here is that we have good mechanical control of our hydrogels — even when they are made inside human cells. This means we can tune them to essentially function as a synthetic version of whatever sequestering phenomenon we want to study, such as how protein aggregation can lead to Alzheimer's."

One key element of this research was that the protein building blocks were designed from scratch — they don't exist anywhere in nature — using computers.

"You can imagine a protein as a string of subunits called amino acids. That string folds up to form a three-dimensional structure. There are 20 different amino acids, and a typical protein is made up of 100 to 200 of them. That makes the system very complex, because how do you know how it's going to fold?" said co-lead author Rubul Mout, who completed this research as a UW postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Protein Design and is now a research fellow at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital. "That's where the computer comes into play — it does calculations to estimate the most likely three-dimensional shape. And similarly, you can tell it what shape you want and it tells you what sequence you need to build the protein."

To make a variety of hydrogels with different properties, the team used computational design to control how floppy or rigid the protein building blocks were and how the building blocks organized and connected to create the hydrogel. The researchers also used two different methods to link the building blocks together: One linked them irreversibly and the other allowed the proteins to disconnect and reconnect.

"Irreversibly crosslinked systems are going to be intrinsically more stable, making them better for long-term cell culture and functional tissue engineering," said DeForest, who is also a faculty member with the UW Molecular Engineering and Sciences Institute and the UW Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine. "But the reversibly crosslinked systems are more fluid, which may be better for driving specific protein-protein interactions within living cells."

To determine if the hydrogels in cells had similar characteristics compared to their extracellular counterparts, the researchers examined whether building blocks within the hydrogels could move around. A stiffer hydrogel would be more likely to trap the proteins in one position compared to a more fluid gel. The mechanical properties of each type of hydrogel remained even when inside a cell.

The team plans to further explore this system, including being able to better control how hydrogels form and localize within cells.

The most crucial part of this project, the researchers said, was the collaboration between protein designers and chemical and biological engineers.

"Our cross-disciplinary collaboration with Cole’s group has been very exciting, and has opened up routes to new classes of biomaterials with a wide range of applications," said co-senior author David Baker, the director of the Institute for Protein Design.

Ross Bretherton, a UW doctoral student in bioengineering, is co-lead author on this paper. Additional co-authors are Justin Decarreau, a UW research scientist in the Institute for Protein Design; Sangmin Lee, an assistant professor at Pohang University of Science and Technology who completed this research as a UW postdoc at the Institute for Protein Design; Nicole Gregorio, a UW doctoral student in bioengineering; Natasha Edman, a UW doctoral student in molecular and cellular biology; Maggie Ahlrichs, a UW doctoral student in biological physics, structure and design; Yang Hsia, a UW research scientist at the Institute for Protein Design; Danny Sahtoe, a group leader at the Hubrecht Institute who completed this research as a postdoc at the Institute for Protein Design; George Ueda, an acting instructor at the Institute for Protein Design; Alee Sharma, an undergraduate student at Northeastern University; and Rebecca Schulman, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Engineering. Mout and Sahtoe were part of the Washington Research Foundation fellowship program. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Audacious Project, the Open Philanthropy Project, the Wu Tsai Translational Investigator Fund, the Center for the Science of Synthesis Across Scales and the National Institutes of Health.

For more information, contact DeForest at profcole@uw.edu, Mout at rubul.mout@childrens.harvard.edu and Baker at dabaker@uw.edu.

END

Using computers to design proteins allows researchers to make tunable hydrogels that can form both inside and outside of cells

2024-01-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

BIPOC individuals bear greater post-COVID burdens

2024-01-31

A study study published today reports that BIPOC individuals who were infected with COVID-19 experienced greater negative aftereffects in health and work loss than did similarly infected white participants.

Despite similar symptom prevalence, Hispanic participants compared to non-Hispanic participants and BIPOC participants compared to white participants had more negative impacts following a COVID-19 infection in terms of health status, activity level and missed work, the authors wrote.

The findings appeared in the journal Frontiers ...

Anchoring single Co sites on bipyridine-based CTF for photocatalytic oxygen evolution

2024-01-31

Photocatalytic water splitting using semiconductors is regarded as a promising technique for producing hydrogen fuel from solar energy. The oxygen evolution half reaction has proven to be the bottleneck for photocatalytic overall water splitting owing to the high energy barrier and the sluggish kinetics. It is a big challenge to develop efficient photocatalysts for the advancement of water oxidation.

Similar to graphene carbon nitride, π-stacked covalent triazine frameworks (CTFs) have gained much attention in photocatalytic water splitting in recent years. The fully conjugated structure with the regular channels in the crystalline network will provide defined pathways for ...

AI-powered app can detect poison ivy

2024-01-31

Poison ivy ranks among the most medically problematic plants. Up to 50 million people worldwide suffer annually from rashes caused by contact with the plant, a climbing, woody vine native to the United States, Canada, Mexico, Bermuda, the Western Bahamas and several areas in Asia.

It’s found on farms, in woods, landscapes, fields, hiking trails and other open spaces. So, if you go to those places, you’re susceptible to irritation caused by poison ivy, which can lead to reactions that require medical attention. Worse, most people don’t know ...

Up to three daily servings of kimchi may lower men’s obesity risk

2024-01-31

Eating up to three daily servings of the Korean classic, kimchi, may lower men’s overall risk of obesity, while radish kimchi is linked to a lower prevalence of midriff bulge in both sexes, finds research published in the open access journal BMJ Open.

Kimchi is made by salting and fermenting vegetables with various flavourings and seasonings, such as onion, garlic, and fish sauce.

Cabbage and radish are usually the main vegetables used in kimchi, which contains few calories and is rich in dietary fibre, microbiome enhancing lactic acid bacteria, vitamins, and polyphenols.

Previously published experimental studies ...

Increase in annual cardiorespiratory fitness by 3%+ linked to 35% lower prostate cancer risk

2024-01-31

An increase in annual cardiorespiratory fitness by 3% or more is linked to a 35% lower risk of developing, although not dying from, prostate cancer, suggests research published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

The findings prompt the researchers to conclude that men should be encouraged to improve their level of fitness to help lower their chances of getting the disease.

There are relatively few known risk factors for prostate cancer, note the researchers. And while there’s good evidence for the beneficial effects of physical activity on ...

High quality diet in early life may curb subsequent inflammatory bowel disease risk

2024-01-31

A high quality diet at the age of 1 may curb the subsequent risk of inflammatory bowel disease, suggests a large long term study, published online in the journal Gut.

Plenty of fish and vegetables and minimal consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks at this age may be key to protection, the findings indicate.

A linked editorial suggests that it may now be time for doctors to recommend a ‘preventive’ diet for infants, given the mounting evidence indicative of biological plausibility.

Cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are increasing globally. Although there is no obvious ...

Next government should declare a national health and care emergency

2024-01-31

The government in post after the election should declare a national health and care emergency, calling on all parts of society to help improve health, care, and wellbeing, say experts in the first report of The BMJ Commission on the Future of the NHS.

The new government should, in effect, relaunch the NHS with a renewed long term vision and plan, they argue.

"The NHS has never seemed so embattled—and its core principle of ‘free to all at the point of use’ has never been so under threat,” said Kamran ...

Unprecedented success continues: 2023 employment gains for people with disabilities outshine those of counterparts without disabilities

2024-01-31

East Hanover, NJ – January 30, 2024 – Amidst the backdrop of a remarkable four-year streak of growth, the employment indicators for people with disabilities reached unprecedented milestones in 2023. This achievement stands in stark contrast to the experiences of people without disabilities who faced a more severe decline during the COVID-19 pandemic and a slower recovery, not surpassing their pre-pandemic employment levels until 2023. That’s according to the National Trends in Disability Employment (nTIDE) 2023 Year-End Special Edition, ...

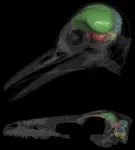

Scientists pinpoint growth of brain’s cerebellum as key to evolution of bird flight

2024-01-31

**EMBARGOED UNTIL 7:01 P.M. ET TUESDAY, JAN 30**

Evolutionary biologists at Johns Hopkins Medicine report they have combined PET scans of modern pigeons along with studies of dinosaur fossils to help answer an enduring question in biology: How did the brains of birds evolve to enable them to fly?

The answer, they say, appears to be an adaptive increase in the size of the cerebellum in some fossil vertebrates. The cerebellum is a brain region responsible for movement and motor control.

The research findings are published in the Jan. 31 issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Scientists have long thought that the cerebellum should be important ...

Machine learning informs a new tool to guide treatment for acute decompensated heart failure

2024-01-30

A recent study co-authored by Dr. Matthew Segar, a third-year cardiovascular disease fellow at The Texas Heart Institute and led by his research and residency mentor, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Dr. Ambarish Pandey, utilized a machine learning-based approach to identify, understand, and predict diuretic responsiveness in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

The study “A Phenomapping Tool and Clinical Score to Identify Low Diuretic Efficiency in Acute Decompensated ...