Rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and scleroderma are examples of autoimmune disorders marked by lopsided female-to-male ratios. The ratio for lupus is 9 to 1; for Sjogren’s syndrome, it’s 19 to 1.

Stanford Medicine scientists and their colleagues have traced this disparity to the most fundamental feature differentiating biological female mammals from males, possibly paving the way for a better way to predict autoimmune disorders before they develop.

“As a practicing physician, I see a lot of lupus and scleroderma patients, because those autoimmune disorders manifest in skin,” said Howard Chang, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and of genetics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “The great majority of these patients are women.”

Chang, the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor in Cancer Research and director of the RNA Medicine Program, is the senior author of the study, to be published Feb. 1 in Cell. Basic life research scientist Diana Dou, PhD, is its lead author.

The silence of the second X

Women have too much of a good thing: It’s called the X chromosome.

Throughout the mammalian kingdom, biological sex is determined by the presence, in every female cell, of two X chromosomes. Males cells pack just one X chromosome, paired with a much shorter one designated the Y chromosome.

The stubby Y chromosome contains only a handful of active genes. It’s quite possible to live a full life without a Y chromosome. In fact, more than half of the people on Earth — women — lack Y chromosomes and do just fine. But no mammalian cell, male or female, can survive without at least one copy of the X chromosome, which holds many hundreds of active protein-specifying genes.

Still, having two X chromosomes risks the production, in every female cell, of twice the amount of the myriad proteins specified by the X but not the Y chromosome. Such massive overproduction of so many proteins would be lethal.

Nature has devised a clever, if complicated, workaround called X-chromosome inactivation. Early in embryogenesis, each cell in the nascent female mammal makes an independent decision to shut down the activity of one or the other of its two X chromosomes. Once that decision is made, it’s handed down to these cells’ progeny in the developing fetus. That way, the same amount of each X-chromosome-specified protein is produced in a female cell as in a male cell.

As the researchers discovered, X-chromosome inactivation can lead to autoimmune disorders, but other factors can also cause these disorders — which is why men sometimes develop them.

The great equalizer

X-chromosome inactivation is achieved courtesy of a molecule called Xist. The gene for Xist is present on all X chromosomes, including the single one male cells have. But Xist itself is produced only when the X chromosome that its gene resides on is one of a matched XX pair — and is produced and deployed on only one member of that pair.

Xist consists of RNA, a substance best known for being a simple-minded messenger that shuttles genes’ instructions for making proteins to the intracellular machines that make them. Yet RNA can do a whole lot more than schlep genetic information. There are as many different kinds of so-called long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) molecules — lengthy RNA stretches that don’t carry instructions for making proteins — as there are of the protein-encoding RNA variety. These lncRNA molecules can park themselves on stretches of chromosomes and change the likelihood that the cellular machinery charged with reading the genes in those locations will do so.

Xist, a type of lncRNA, is much longer than most. Xist coats long sections of one of a female mammalian cell’s two X chromosomes — but always just one — cutting that chromosome’s output to zero or close to it. The other X chromosome, left undisturbed, pumps out just enough RNA-encoded instructions to keep the cell humming.

But Xist’s nestling into the extra X chromosome generates odd combinations of lncRNA, proteins that bind to it, other proteins that bind to those proteins, and DNA some of those proteins cling to. These complexes can trigger a strong immune response, Chang and his colleagues have learned.

In 2015, Chang’s group identified close to 100 proteins that either bound to Xist or that bound to those proteins, collectively enabling this molecule to lay anchor along gene-specifying regions of the X chromosome.

Inspecting this Xist “parts list,” Chang realized that many of Xist’s collaborator proteins were known to be associated with autoimmune disorders. Might the RNA-protein-DNA complexes generated in the course of X-chromosome inactivation be triggering the notoriously high rate of autoimmunity in women compared with men? That question was the impetus for the new study.

What if males made Xist?

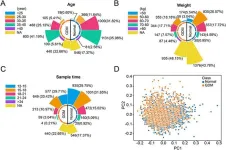

To eliminate possible competing causes such as female hormonal action or aberrant protein production by the supposedly silenced second X chromosome, the researchers tossed the Xist ball into the male court. They sewed the gene for Xist into the genomes of two different strains of male lab mice. One strain is quite susceptible to autoimmune symptoms mimicking lupus, with females more susceptible than males. The other is resistant to it.

The inserted Xist gene had been modified in two ways. It could be turned on or off by chemical means, pumping out Xist only when the scientists wanted it to. The Xist gene was also tweaked slightly so that its RNA product would no longer silence the genes of the male mouse’s chromosome into which it was stitched.

Merely inserting that modified Xist gene had no noticeable effect on the mice. But the Xist produced from the inserted gene, once that gene was activated, still formed characteristic complexes with almost all the proteins found earlier to be collaborating closely with Xist.

Now, the scientists could ask: Is a bioengineered male mouse that’s been coaxed to produce Xist more prone to autoimmunity than a normal male mouse, which never produces it, or than a male in whom the gene for Xist has been inserted but not activated?

By injecting an irritant known to induce a lupus-like autoimmune condition in the susceptible mouse strain, the investigators could compare its effect on males who made Xist with its effect on normal males, who made none.

In these susceptible mice, males in which the Xist gene was activated developed lupus-like autoimmunity at a rate approaching that of females — and considerably more so than non-bioengineered males.

The absence of autoimmunity in some female or Xist-activated male mice in the susceptible strain showed that not just activation of Xist but also some kind of tissue-damaging stress (caused, in this case, by injection of the irritant) is required to get the autoimmunity ball rolling.

In the autoimmune-resistant strain, activating Xist in bioengineered male mice wasn’t enough to induce autoimmunity — as might be predicted by the fact that in this strain even females seldom develop autoimmunity. That suggests that not only Xist activation but also an appropriate genetic background is necessary for autoimmunity to develop.

These constraints on autoimmunity are fortunate, because if there were none all women might be more susceptible to develop immunity, Chang noted.

Toward a better autoimmunity-screening panel

An early step in the development of autoimmunity is the appearance of autoantibodies: antibodies targeting one’s own tissues or cell products. Autoantibodies to the contents of cell nuclei are called anti-nuclear antibodies. Close examination of blood samples from about 100 patients with autoimmunity showed the presence of autoantibodies to many of the complexes associated with Xist. Some of these autoantibodies were specific to one or another autoimmune disorder, indicating their potential utility in identifying particular emergent autoimmune disorders before symptoms develop. Autoantibodies to still other Xist-associated proteins spanned several disorders, designating them as possible common markers of autoimmunity.

“Every cell in a woman’s body produces Xist,” Chang said. “But for several decades, we’ve used a male cell line as the standard of reference. That male cell line produced no Xist and no Xist/protein/DNA complexes, nor have other cells used since for the test. So, all of a female patient’s anti-Xist-complex antibodies — a huge source of women’s autoimmune susceptibility — go unseen.”

Researchers from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, in Stockholm; and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, in Zurich, contributed to the work.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants T32AR007422, K99/R00 and T32AR050942), the Scleroderma Research Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END