(Press-News.org)

All animals need to regulate their body temperature and cannot survive for long if it gets too high or too low. Warm-blooded organisms like humans have various ways to do this. They release heat by sweating or expanding the blood vessels in their skin, while shivering or burning fat in their brown adipose tissue has the opposite effect.

Cold-blooded animals such as the zebrafish, by contrast, cannot do any of these, so they have a different strategy. They look for places nearby that are at their “comfortable temperature,” just like how we might go out into the sun when we feel chilly or seek out some shade once it gets too hot. “We formed the idea that cold-blooded organisms use similar brain mechanisms to humans to find the ideal temperature conditions for them and that these help them to know where to go,” explains Professor Ilona Grunwald Kadow from the Institute of Physiology II at the University of Bonn and the University Hospital Bonn.

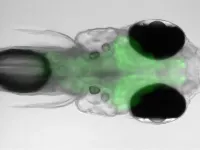

Fish larvae observed “thinking”

The zebrafish is perfect for testing this idea because its larvae are transparent. This allows scientists to look inside their brains while they perform certain tasks in the laboratory—and these researchers did just that. “The animals had been genetically modified to make their nerve cells produce a dye,” explains Grunwald Kadow from the University Hospital Bonn, who is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Life & Health” at the University of Bonn. “This caused their neurons to light up when they were active, enabling us to see under the microscope which areas of their brains were working at that precise moment.”

In their experiments, the researchers surrounded the animals with water that they made hotter or colder. “Then we watched to see how they’d react,” Virginia Palieri explains. For her doctorate at TUM, she studied the degree of similarity between the mechanisms for regulating body temperature used by cold-blooded animals and their warm-blooded counterparts such as humans. “This told us that the fish prefer a temperature of 25.3 degrees Celsius. As soon as it got a few tenths of a degree cooler or warmer, they began to seek out more comfortable surroundings.”

“Satnav” increases the chances of finding ideal living conditions quickly

Two parts of their brain are activated in this process, the preoptic area of the hypothalamus (POA) and the dorsal habenula. The POA seems to be primarily responsible for detecting deviations from the fish’s ideal temperature. “When we switched off the animals’ POA, they stopped embarking on searches, even when the temperature of their water was some way off what made them comfortable,” Palieri says. Interestingly, mammals like us have a POA too. “And this region of the brain is likewise responsible for regulating temperature, even in these much more highly developed organisms,” Grunwald Kadow explains. “In them, however, it’s mainly responsible for automatic actions such as sweating or shivering—behavior less so.” Nevertheless, the study has revealed that the brain’s “thermostat” is extremely ancient, meaning that it developed very early on in the evolutionary process.

The habenula, for its part, clearly acts as a kind of “satnav,” showing the fish where it can locate a comfortable temperature and guiding it straight back there. “Thanks to their navigation system, the animals can find their way around very efficiently and make their way back quickly to the spot with the best temperature,” adds Professor Ruben Portugues from the Institute of Neuroscience at TUM and researcher in the Cluster of Excellence “SyNergy”, who led the study together with Ilona Grunwald Kadow.

Deactivating the habenula region robs the fish of its ability to find its way around and forces it to adopt a different search strategy similar to bacteria and other single-celled organisms: it swims in a straight line for a while and then checks whether the temperature has changed to its liking. If so, it carries on in the same direction; if not, it picks a different direction at random and swims off again, repeating the process until it has found somewhere with a more suitable temperature.

Although we still know very little about how exactly the zebrafish’s navigation system works, it is believed to involve special “compass cells.” The habenula might potentially store its location, enabling it to reconstruct sequences of movement. “We now want to examine this hypothesis more closely,” Professor Portugues says. What is also intriguing is that this navigation system is clearly not only used to hunt for places at the right temperature. It also helps to re-locate areas with a good salt level, pH or similar conditions or resources that the fish need in order to survive.

This shows how efficient the brain is: once it has found a solution to a certain problem, it is only too happy to use it for other, similar tasks as well. And this is not just true of individual species, since these solutions have been retained and improved on over the course of evolution.

Institutions involved and funding secured:

TUM, the University of Bonn, the University Hospital Bonn and Ohio State University in the US were involved in the study, which was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Volkswagen Foundation and the European Research Council (ERC).

END

While newly approved drugs for Alzheimer’s show some promise for slowing the memory-robbing disease, the current treatments fall far short of being effective at regaining memory. What is needed are more treatment options targeted to restore memory, said Buck Assistant Professor Tara Tracy, PhD, the senior author of a study that proposes an alternate strategy for reversing the memory problems that accompany Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Since most current research on potential treatments for Alzheimer’s focuses on reducing the toxic proteins, such as tau and amyloid beta, that accumulate in ...

(Boston)—One of the major challenges in cancer research and clinical care is understanding the molecular basis for therapeutic resistance as a major cause of long term treatment failures. In cases of melanoma, the main targeted therapeutic strategy is directed against the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Unfortunately, in the vast majority of these patients, resistance to MAPK inhibitor therapies develops within one year of treatment.

In a new study from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, ...

During the COVID-19 pandemic, lower occupancy in buildings led to reduced water use, raising concerns about water quality due to stagnation. Government warnings highlighted increased risks of chemical and microbiological contamination in water systems. Studies showed that reduced usage and stagnation could elevate heavy metal levels and decrease disinfectant effectiveness, affecting microbial growth. To address this, regular fixture flushing was recommended, which temporarily improved water quality but also revealed the complexities of managing building water systems effectively.

In a recent study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2023.100314) ...

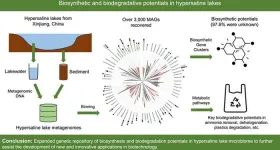

The study delves into hypersaline lakes in Xinjiang, China, exploring the genetic and metabolic diversity of microbial communities termed "microbial dark matters". Hypersaline lake ecosystems, characterized by extreme salinity, harbor unique microorganisms with largely unexplored biosynthesis and biodegradation capabilities. The research seeks to uncover novel biological compounds and pathways, potentially revolutionizing biotechnology, medicine, and environmental remediation by tapping into the untapped potential of these extremophiles.

A recent study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2023.100359) published ...

While surgery to remove rectal cancer can be necessary and lifesaving, it can sometimes come with significant drawbacks, like loss of bowel control. According to a study led by Wilmot Cancer Institute researchers, patients with rectal cancer who respond well to radiation and chemotherapy are increasingly foregoing surgery and opting for a watch-and-wait approach.

The study, published in JAMA Oncology, shows that the number of patients opting out of surgery rose nearly 10 percent between 2006 and 2020. These data reflect a shift toward what ...

Somewhere between 24 and 50 million Americans have an autoimmune disease, a condition in which the immune system attacks our own tissues. As many as 4 out of 5 of those people are women.

Rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and scleroderma are examples of autoimmune disorders marked by lopsided female-to-male ratios. The ratio for lupus is 9 to 1; for Sjogren’s syndrome, it’s 19 to 1.

Stanford Medicine scientists and their colleagues have traced this disparity to the most fundamental feature differentiating ...

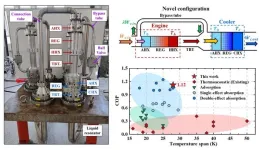

Researchers led by Prof. LUO Ercang from the Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry (TIPC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and their collaborators have developed an innovative heat-driven thermoacoustic refrigerator (HDTR) with a novel bypass configuration that significantly improves the efficiency of this technology.

The study was published in Cell Reports Physical Science on Feb. 1.

HDTR is recognized as a new, promising cooling technology with many advantages. For example, it has no moving parts, uses eco-friendly substances (e.g., helium and nitrogen), and is highly reliable. However, its relatively low efficiency ...

Small long-nosed (or dolichocephalic) dog breeds such as Whippets have the highest life expectancies in the UK, whilst male dogs from medium-sized flat-faced (or brachycephalic) breeds such as English Bulldogs have the lowest. The results, published in Scientific Reports, have been calculated from data on over 580,000 individual dogs from over 150 different breeds, and could help to identify those dogs most at risk of an early death.

Kirsten McMillan and colleagues assembled a database of 584,734 individual dogs using data from 18 different UK sources, including breed registries, vets, pet insurance companies, animal welfare ...

About The Study: Physical activity was associated with better late-life cognition, but the association was weak in this systematic review and meta-analysis including 104 studies with 341,000 participants. However, even a weak association is important from a population health perspective.

Authors: Paula Iso-Markku, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Helsinki, Finland is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54285)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

About The Study: In this study of 205 adolescent football players and 70 noncontact control athletes, there was evidence of discernible structural and physiological differences in the brains of adolescent football players compared with their noncontact controls. Many of the affected brain regions were associated with mental health well-being.

Authors: Keisuke Kawata, Ph.D., of Indiana University in Bloomington, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54235)

Editor’s ...