(Press-News.org) UC Riverside scientists have discovered a tiny worm species that infects and kills insects. These worms, called nematodes, could control crop pests in warm, humid places where other beneficial nematodes are currently unable to thrive.

This new species is a member of a family of nematodes called Steinernema that have long been used in agriculture to control insect parasites without pesticides. Steinernema are not harmful to humans or other mammals and were first discovered in the 1920s.

“We spray trillions of them on crops every year, and they’re easy to buy,” said UCR nematology professor Adler Dillman, whose lab made the discovery. “Though there are more than 100 species of Steinernema, we’re always on the lookout for new ones because each has unique features. Some might be better in certain climates or with certain insects.”

Hoping to gain a deeper understanding of a different Steinernema species, Dillman’s laboratory requested samples from colleagues in Thailand. “We did DNA analysis on the samples and realized they weren’t the ones we had requested. Genetically, they didn’t look like anything else that has ever been described,” Dillman said.

Dillman and his colleagues have now described the new species in the Journal of Parasitology. They are nearly invisible to the naked eye, about half the width of a human hair and just under 1 millimeter long. “Several thousand in a flask looks like dusty water,” Dillman said.

They’ve named the new species Steinernema adamsi after the American biologist Byron Adams, Biology Department chair at Brigham Young University.

“Adams has helped refine our understanding of nematode species and their important role in ecology and recycling nutrients in the soil,” Dillman said. “He was also my undergraduate advisor and the person who introduced me to nematodes. This seemed a fitting tribute to him.”

Adams, who is currently doing research on nematodes in Antarctica, said he is honored to have such a “cool” species bear his name in the scientific literature.

“The biology of this animal is absolutely fascinating,” Adams said. “Aside from its obvious applications for alleviating human suffering caused by pest insects, it also has much to teach us about the ecological and evolutionary processes involved in the complex negotiations that take place between parasites, pathogens, their hosts, and their environmental microbiomes.”

Learning about these worms’ life cycles as an undergraduate is what hooked Dillman on studying them. As juveniles, nematodes live in the soil with sealed mouths, in a state of arrested development. In that stage, they wander the soil looking for insects to infect. Once they find a victim, they enter the mouth or anus and defecate highly pathogenic bacteria.

“A parasite that poops out pathogenic stuff to help kill its host, that’s unusual right out of the gate,” Dillman said. “It’s like something out of a James Cameron movie.”

Within 48 hours of infection, the insect dies. “It essentially liquefies the insect, then you’re left with a bag that used to be its body. You might have 10 or 15 nematodes in a host, and 10 days later you have 80,000 new individuals in the soil looking for new insects to infect,” Dillman said.

The researchers are certain that S. adamsi kills insects. They confirmed this by putting some of them in containers with wax moths. “It killed the moths in two days with a very low dose of the worms,” Dillman said.

Going forward, the researchers hope to discover the nematode’s unique properties. “We don’t know yet if it can resist heat, UV light, or dryness. And we don’t yet know the breadth of insects it is capable of infecting.

However, S. adamsi are members of a genus that can infect hundreds of types of insects. Therefore, the researchers are confident it will be beneficial on some level whether it turns out to be a specialist or a generalist parasite of multiple types of insects.

“This is exciting because the discovery adds another insect-killer that could teach us new and interesting biology,” Dillman said. “Also they’re from a warm, humid climate that could make them a good parasite of insects in environments where currently, commercially available orchard nematodes have been unable to flourish.”

END

Surprise discovery of tiny insect-killing worm

New nematode species could protect crops without pesticides

2024-02-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Are environmental toxins putting future generations at risk?

2024-02-08

In a study that signals potential reproductive and health complications in humans, now and for future generations, researchers from McGill University, the University of Pretoria, Université Laval, Aarhus University, and the University of Copenhagen, have concluded that fathers exposed to environmental toxins, notably DDT, may produce sperm with health consequences for their children.

The decade-long research project examined the impact of DDT on the sperm epigenome of South African Vhavenda and Greenlandic ...

Protecting the protector boosts plant oil content

2024-02-08

UPTON, NY—Biologists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have demonstrated a new way to boost the oil content of plant leaves and seeds. As described in the journal New Phytologist, the scientists identified and successfully altered key portions of a protein that protects newly synthesized oil droplets. The genetic alterations essentially protect the oil-protector protein so more oil can accumulate.

“Implementing this strategy in bioenergy or oil crop plants could ...

Physical activity is insufficient to counter cardiovascular risk associated with sugar-sweetened beverage consumption

2024-02-08

Québec, February 8, 2024 - Contrary to popular belief, the benefits of physical activity do not outweigh the risks of cardiovascular disease associated with drinking sugar-sweetened beverages, according to a new study led by Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Jean-Philippe Drouin-Chartier, professor at Université Laval’s Faculty of Pharmacy, was a co-author.

Sugar-sweetened beverages are the largest source of added sugars in the North American diet. Their consumption is associated with ...

CARB-X funds Visby Medical to develop a portable rapid diagnostic for gonorrhea including antibiotic susceptibility

2024-02-08

(BOSTON: Thursday, February 8, 2024) – Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will award up to US$1.8 million to biotechnology company, Visby Medical, to develop a portable rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnostic to detect the presence of the pathogen that causes gonorrhea, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), and its susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, a former frontline oral antibiotic that can no longer treat resistant NG. A rapid result on when ciprofloxacin may be effective could enable physicians to treat gonorrhea patients with confidence, while reserving ceftriaxone, the only antibiotic that remains effective against resistant NG.

Visby ...

Fusion research facility JET’s final tritium experiments yield new energy record

2024-02-08

GARCHING and OXFORD (8 February 2024) –

The Joint European Torus (JET), one of the world’s largest and most powerful fusion machines, has demonstrated the ability to reliably generate fusion energy, whilst simultaneously setting a world-record in energy output.

These notable accomplishments represent a significant milestone in the field of fusion science and engineering.

In JET's final deuterium-tritium experiments (DTE3), high fusion power was consistently produced for 5 seconds, resulting in a ground-breaking record of 69 megajoules using a mere 0.2 milligrams of fuel.

JET is a tokamak, a design which uses powerful ...

A new “metal swap” method for creating lateral heterostructures of 2D materials

2024-02-08

Electronically conducting two-dimensional (2D) materials are currently hot topics of research in both physics and chemistry owing to their unique properties that have the potential to open up new avenues in science and technology. Moreover, the combination of different 2D materials, called heterostructures, expands the diversity of their electrical, photochemical, and magnetic properties. This can lead to innovative electronic devices not achievable with a single material alone.

Heterostructures can be fabricated in two ways: vertically, with materials ...

Study visually captures a hard truth: Walking home at night is not the same for women

2024-02-08

An eye-catching new study shows just how different the experience of walking home at night is for women versus men.

The study, led by Brigham Young University public health professor Robbie Chaney, provides clear visual evidence of the constant environmental scanning women conduct as they walk in the dark, a safety consideration the study shows is unique to their experience.

Chaney and co-authors Alyssa Baer and Ida Tovar showed pictures of campus areas at four Utah universities — Utah Valley University, ...

Ice cores provide first documentation of rapid Antarctic ice loss in the past

2024-02-08

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and the British Antarctic Survey have uncovered the first direct evidence that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet shrunk suddenly and dramatically at the end of the Last Ice Age, around eight thousand years ago.

The evidence, contained within an ice core, shows that in one location the ice sheet thinned by 450 metres — that’s more than the height of the Empire State Building — in just under 200 years.

This is the first evidence anywhere in Antarctica for such a fast loss of ice. Scientists are worried that today’s rising temperatures ...

Faulty DNA disposal system causes inflammation

2024-02-08

LA JOLLA (February 8, 2024)—Cells in the human body contain power-generating mitochondria, each with their own mtDNA—a unique set of genetic instructions entirely separate from the cell’s nuclear DNA that mitochondria use to create life-giving energy. When mtDNA remains where it belongs (inside of mitochondria), it sustains both mitochondrial and cellular health—but when it goes where it doesn’t belong, it can initiate an immune response that promotes inflammation.

Now, Salk scientists ...

Breaking through barriers

2024-02-08

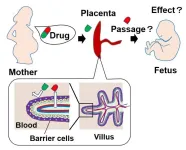

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) overcome scientific roadblocks and develop a model to assess the biology of the human placental barrier

Tokyo, Japan – During pregnancy, the human placenta plays multiple essential roles, including hormone production and nutrient/waste processing. It also serves as a barrier to protect the developing fetus from external toxic substances. However, the placental barrier can still be breached by certain drugs. In a recent article published in Nature Communications, a team led by researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

[Press-News.org] Surprise discovery of tiny insect-killing wormNew nematode species could protect crops without pesticides