(Press-News.org) Living cells resemble highly organized small towns - in addition to energy production, transportation systems, and construction, cells also require efficient waste disposal. Most proteins, which shape and sustain cellular function, have only a limited half-life and must eventually be disposed of, along with defective and unwanted proteins. This vital task falls upon specialized enzymes known as ubiquitin ligases, which tag obsolete proteins for degradation, guiding them to the cellular recycling center, the proteasome. Ubiquitin, acting as molecular label, ensures the targeted proteins are efficiently processed for disposal.

Yet, cells are not always able to recognize and mark every harmful protein with ubiquitin accordingly. Many diseases such as cancer or neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's can only arise because harmful proteins accumulate in cells. This is where the research of Georg Winter's group at CeMM comes in: with a technique called "targeted protein degradation," harmful or otherwise unwanted proteins can be marked with ubiquitin and destroyed in the proteasome, effectively reprogramming the cell's waste disposal system.

So far, this has worked in one of two ways: either by introducing a chemical agent (so-called PROTACs) into the cell, which attaches to one side of the protein to be degraded and to the ubiquitin ligase on the other side, thereby directly linking the two and marking the undesired protein for degradation. Or, by introducing a kind of "molecular glue" into the cell, which attaches to the ligase and thereby induces it to recognize and mark the unwanted protein for degradation. In the new study, now published in Nature (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07089-6), the team led by Georg Winter (CeMM) and Alessio Ciulli (University of Dundee) has revealed a third way that combines both of these existing strategies: so-called "intramolecular bivalent glues" (IBGs) attach to two points on the protein to be degraded, slightly bending it and thereby altering its surface. This alteration is recognized by a ubiquitin ligase, thus marking the protein for degradation.

"This method opens up completely new possibilities for the development of drugs that can be used against cancer, among other diseases" says Georg Winter. "Together with other targeted protein degradation methods, this could potentially treat many diseases that have previously been undruggable." "So far, we often discover drugs that lead to targeted protein degradation only by chance. However, the better we understand how this system works, the closer we come to being able to design such drugs deliberately," says Matthias Hinterndorfer, a postdoctoral researcher in Georg Winter's research group. Therefore, the new discovery provides important insights into the mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities of targeted protein degradation.

###

The CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences is an international, independent and interdisciplinary research institution for molecular medicine under the scientific direction of Giulio Superti-Furga. CeMM is oriented towards medical needs and integrates basic research and clinical expertise to develop innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for precision medicine. Research focuses on cancer, inflammation, metabolic and immune disorders, and rare diseases. The Institute's research building is located on the campus of the Medical University and the Vienna General Hospital.

www.cemm.at

For further information please contact:

Stefan Bernhardt

PR & Communications Manager

CeMM

Research Center for Molecular Medicine

of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

Lazarettgasse 14, AKH BT 25.3

1090 Vienna, Austria

Phone +43-1/40160-70 056

Fax +43-1/40160-970 000

sbernhardt@cemm.at

www.cemm.at

END

New system triggers cellular waste disposal

2024-02-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Possible trigger for autoimmune diseases discovered : B cells teach T cells which targets must not be attacked

2024-02-21

Immune cells must learn not to attack the body itself. A team of researchers from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) has discovered a previously unknown mechanism behind this: other immune cells, the B cells, contribute to the "training" of the T cells in the thymus gland. If this process fails, autoimmune diseases can develop. The study confirms this for Neuromyelitis optica, a disease similar to Multiple Sclerosis. Other autoimmune diseases may be linked to the failure ...

Detecting pathogens faster and more accurately by melting DNA

2024-02-21

A new analysis method can detect pathogens in blood samples faster and more accurately than blood cultures, which are the current state of the art for infection diagnosis. The new method, called digital DNA melting analysis, can produce results in under six hours, whereas culture typically requires 15 hours to several days, depending on the pathogen.

Not only is this method faster than blood cultures, it’s also significantly less likely to generate false positives compared to other emerging DNA detection-based technologies such as Next Generation Sequencing.

Why ...

MD Anderson research highlights for February 21, 2024

2024-02-21

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Recent developments at MD Anderson offer insights into drug-drug interactions for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes; patient-derived xenograft models as a viable translational ...

Engineers use AI to wrangle fusion power for the grid

2024-02-21

In the blink of an eye, the unruly, superheated plasma that drives a fusion reaction can lose its stability and escape the strong magnetic fields confining it within the donut-shaped fusion reactor. These getaways frequently spell the end of the reaction, posing a core challenge to developing fusion as a non-polluting, virtually limitless energy source.

But a Princeton-led team composed of engineers, physicists, and data scientists from the University and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have harnessed ...

UChicago scientists invent ultra-thin, minimally-invasive pacemaker controlled by light

2024-02-21

Sometimes our bodies need a boost. Millions of Americans rely on pacemakers—small devices that regulate the electrical impulses of the heart in order to keep it beating smoothly. But to reduce complications, researchers would like to make these devices even smaller and less intrusive.

A team of researchers with the University of Chicago has developed a wireless device, powered by light, that can be implanted to regulate cardiovascular or neural activity in the body. The featherlight membranes, ...

Accelerometer-measured physical activity, sedentary time, and heart failure risk in older women

2024-02-21

About The Study: The results of this study of 5,951 women ages 63 to 99 suggest that promoting regular physical activity and minimal sedentary time may be prudent for primary prevention of heart failure and its subtype with preserved ejection fraction for which treatment is limited.

Authors: Michael J. LaMonte, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University at Buffalo—SUNY, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2023.5692)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Lifetime suicide attempts in otherwise psychiatrically healthy individuals

2024-02-21

About The Study: In this study using data from 1,948 U.S. adults with lifetime suicide attempts from a nationally representative population-based survey, an estimated 19.6% reported not having met criteria for any psychiatric disorders prior to their first attempt. This finding challenges clinical notions of who is at risk for suicidal behavior and raises questions about the safety of limiting suicide risk screening to psychiatric populations.

Authors: Maria A. Oquendo, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media ...

Acupuncture for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder

2024-02-21

About The Study: The acupuncture intervention used in this randomized clinical trial including 93 participants was clinically efficacious and favorably affected the psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans. These data build on extant literature and suggest that clinical implementation of acupuncture for PTSD, along with further research about comparative efficacy, durability, and mechanisms of effects, is warranted.

Authors: Michael Hollifield, M.D., of the Tibor Rubin VA Medical Center in Long Beach, California, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5651)

Editor’s ...

Study finds high number of persistent COVID-19 infections in the general population

2024-02-21

New study finds that persistent COVID-19 infections are surprisingly common, with around one to three in every 100 infections lasting a month or longer.

Some persistent infections had a high number of mutations, suggesting they could act as reservoirs to seed new variants of concern.

People with persistent infections lasting for 30 days or longer were 55% more likely to report having Long Covid than people with more typical infections.

Reinfections with the same variant were rare.

A new study led by the University of Oxford has ...

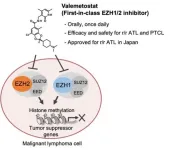

Researchers reveal mechanism of drug reactivating tumor suppressors

2024-02-21

Researchers have revealed the mechanism of a drug shown to be effective in treating certain types of cancer, which targets a protein modification silencing the expression of multiple tumor suppressor genes. They also demonstrated in clinical trials the efficacy of the drug in reducing tumor growth in blood cancer. The findings could lead to longer-term treatments for the disease and therapies for other types of cancer with similar underlying causes.

A team of researchers from the University of Tokyo and their collaborators focused on therapies targeting H3K27me3, a modification on a DNA-packaging histone protein, which plays a large role in regulating ...