(Press-News.org) One of the great unresolved mysteries of human evolution is how pro-social, cooperative behavior could have evolved. What led to the establishment of a behavior that prioritizes the benefit of the community over that of the individual in a world where materially successful individuals reproduce, and others slowly perish?

The prevailing theory suggests that this occurred due to repeated interactions. Over generations, humans learned that cooperative behavior pays off in the long run. People collaborate because they anticipate interacting with the same individuals in the future. Therefore, those who behave antisocially suffer reputational damage and are punished by others with uncooperative behavior, manifesting that uncooperative behavior does not pay off in the long run.

Exchange experiment in Papua New Guinea

However, there is strong empirical evidence that people behave cooperatively even in non-recurrent and anonymous interactions where there is no risk of reputational damage. How can this be explained? Behavioral economists from the Universities of Zurich, Lausanne and Konstanz addressed this question by conducting an experiment among indigenous people in Papua New Guinea.

In a setup resembling a trust game, pairs of individuals had to exchange money with each other and to decide whether they wanted to act selfishly and uncooperatively or rather socially and cooperatively (see box). The conclusion: when paired with an anonymous member of their own community, participants exchanged very large amounts. In pairings with members of other communities, however, very little was transferred.

Prevailing paradigm challenged

In a comprehensive theoretical analysis linked with the experiment, the researchers show that the prevailing theory of repeated interactions alone cannot explain the evolution of human cooperation, since repeated interactions only enable the evolution of cooperation if the individual ability to reduce cooperation is arbitrarily restricted. Without such arbitrary restrictions, cooperation collapses.

This is because even in repeated interactions, there is an incentive to gain an advantage by always cooperating a little less than the partner. Over time, this leads to a breakdown in cooperation. "This is perhaps the most provocative result of our study, as it completely contradicts the mainstream,” says corresponding author Ernst Fehr of the University of Zurich.

Cooperating groups compete with each other

A second common thesis on how cooperation could evolve also falls short: the idea that groups with several team-oriented members fare better in competition – and that general cooperation spreads because less cooperative groups die out. However, the theoretical analysis shows that the migration of cooperative and non-cooperative individuals between groups weakens the cooperative groups. Furthermore, there is also competition between cooperative groups, which weakens overall cooperation in the population.

Combined, “super-additive” approach is key

So how can the obvious fact be explained that people often behave very cooperatively even in one-time interactions? The authors show that this can be explained by the simultaneous interaction of both mechanisms. They found that the two well-known mechanisms, “repeated interactions” and “group competition,” synergistically interact and lead to a form of super-additive cooperation.

First author Charles Efferson of the University of Lausanne summarizes the study’s results as follows: “Repeated interactions create an incentive for cooperation within the group. However, this is a fragile state. Group competition, on the other hand, has a stabilizing effect on this fragile state. This strengthens intra-group cooperation on the one hand and promotes uncooperative behavior with outsiders on the other.” Thus, social motives seem to have developed in human history under the combined influence of both mechanisms.

Literature:

Charles Efferson, Helen Bernhard, Urs Fischbacher, and Ernst Fehr (2024): Super-additive cooperation. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07077-w

((Box))

Experiment in Papua New Guinea

The participants were each given five monetary units in local currency, equivalent to half a day's wages. They were then divided into pairs and a one-time interaction between the people took place, an anonymous sequential exchange. Person 1 was asked to decide how much of the five monetary units they wanted give to person 2, knowing that the amount would be doubled and given to person 2. This decision was announced to person 2. Person 2 could now decide how much of their five monetary units they would like to give to person 1. This amount was also doubled. This lead to a situation in which the reciprocal transfer of monetary units (= co-operation) is advantageous for both parties. However, if person 2 acted selfishly and transferred nothing to person 1, and if person 1 expected this and also acted selfishly, they would also transfer nothing to person 2.

Contact:

Ernst Fehr

University of Zurich

Professor of Economics

Director of the UBS Center for Economics in Society

Phone : +41 44 634 37 09

E-mail: ernst.fehr@econ.uzh.ch

Charles Efferson

University of Lausanne

Professor of Economics

Phone: +41 21 692 61 34

E-mail: charles.efferson@unil.ch

END

Combination of group competition and repeated interactions promotes cooperation

2024-02-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A new beginning: The search for more temperate Tatooines

2024-02-22

New Haven, Conn. — Luke Skywalker’s childhood might have been slightly less harsh if he’d grown up on a more temperate Tatooine — like the ones identified in a new, Yale-led study.

According to the study’s authors, there are more climate-friendly planets in binary star systems — in other words, those with two suns — than previously known. And, they say, it may be a sign that, at least in some ways, the universe leans in the direction of orderly alignment rather than chaotic misalignment.

For the study, ...

Moffitt study highlights urgent need to address impact of extreme weather events on cancer survivorship

2024-02-22

TAMPA, Fla. — Hurricanes and other extreme weather events pose immediate threats to life and property and have long-lasting impacts on health outcomes, particularly for cancer survivors. In a mini-review published today in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal from the American Association for Cancer Research, Moffitt Cancer Center researchers shed light on the significant gaps in understanding and addressing the effects of hurricanes and extreme weather events on biological, psychosocial and clinical outcomes among cancer survivors.

Researchers ...

Scientists can tell where a mouse is looking and located based on its neural activity

2024-02-22

Researchers have paired a deep learning model with experimental data to “decode” mouse neural activity. Using the method, they can accurately determine where a mouse is located within an open environment and which direction it is facing just by looking at its neural firing patterns. Being able to decode neural activity could provide insight into the function and behavior of individual neurons or even entire brain regions. These findings, publishing February 22 in Biophysical Journal, could also inform the design of intelligent machines that currently ...

Artificial intelligence matches or outperforms human specialists in retina and glaucoma management, Mount Sinai study finds

2024-02-22

A large language model (LLM) artificial intelligence (AI) system can match, or in some cases outperform, human ophthalmologists in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with glaucoma and retina disease, according to research from New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai (NYEE).

The provocative study, published February 22, in JAMA Ophthalmology, suggests that advanced AI tools, which are trained on vast amounts of data, text, and images, could play an important role in providing decision-making support to ophthalmologists in the diagnosis and management of cases involving glaucoma and retina ...

A third of trans masculine individuals on testosterone ovulate

2024-02-22

"Trans masculine people are people born female but do not identify as such, for example they feel male, gender fluid or non-binary. Our examination of their ovarian tissue shows that 33% of them show signs of recent ovulation, despite being on testosterone and no longer menstruating," says Joyce Asseler, PhD candidate at Amsterdam UMC.

Trans masculine people often use hormone treatment with testosterone to masculinize physically. This hormone usually stops them from menstruating. In that ...

Researchers use deep brain stimulation to map therapeutic targets for four brain disorders

2024-02-22

A new study led by investigators from Mass General Brigham demonstrated the use of deep brain stimulation (DBS) to map a ‘human dysfunctome’ — a collection of dysfunctional brain circuits associated with different disorders. The team identified optimal networks to target in the frontal cortex that could be used for treating Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette's syndrome. Their results are published in Nature Neuroscience.

“We were able to use brain stimulation to precisely identify and target circuits for the optimal treatment of four different ...

Undiagnosed cancer cases in the US during the first 10 months of the pandemic

2024-02-22

About The Study: This study found that all-sites cancer incidence in the U.S. was significantly lower than expected in March through December 2020, with 134,395 potentially undiagnosed cancer cases. The overall and differential findings can be used to inform where the health care system should be looking to make up ground in cancer screening and detection.

Authors: Krystle A. Lang Kuhs, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of Kentucky in Lexington, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.6969)

Editor’s ...

Uncorrected refractive error in the African American eye disease study

2024-02-22

About The Study: The results of this study suggest a high burden of refractive error–associated correctable refractive error in African American adults, making it the leading cause of visual impairment in this population. Providing universal coverage for vision care and prescription glasses is an affordable and achievable health care intervention that could reduce the burden of visual impairment in African American adults by over two-thirds and likely raise the quality of life and work productivity, ...

Vision impairment and psychosocial function in older adults

2024-02-22

About The Study: Vision impairment was associated with several psychosocial outcomes, including symptoms of depression and anxiety and social isolation in this study including 2,822 U.S. adults age 65 and older. These findings provide evidence to support prioritizing research aimed at enhancing the health and inclusion of people with vision impairment.

Authors: Pradeep Y. Ramulu, M.D., M.H.S., Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed ...

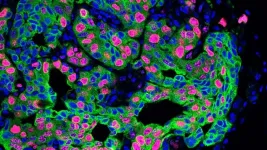

Chronic stress spreads cancer … here’s how

2024-02-22

Stress is inevitable. But too much of it can be terrible for our health. Chronic stress can increase our risk for heart disease and strokes. It may also help cancer spread. How this works has remained a mystery—a challenge for cancer care.

Xue-Yan He, a former postdoc in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Adjunct Professor Mikala Egeblad’s lab, says, “Stress is something we cannot really avoid in cancer patients. You can imagine if you are diagnosed, you cannot stop thinking about the disease or insurance ...