(Press-News.org)

TORONTO, March 5, 2024 – Will ice floating in the Arctic Ocean move faster or slower over the coming decades? The answer to this question will tell us whether marine transportation can be expected to get more or less hazardous. It might also have important implications for the rate of ice cover loss, which is hugely consequential for Northern Indigenous communities, ecosystems, and the global climate system.

While observational data suggest the trend has been towards faster sea ice speeds, climate models project that those speeds will slow down during the summer season. This contrast has led to some questions around the plausibility of the model projections.

In a new paper published today in The Cryosphere, Lassonde School of Engineering Associate Professor Neil Tandon and Postdoctoral Visitor Jamie Ward found that, while the mechanisms driving the ice slowdown remain plausible, questions remain regarding the timing of the slowdown.

“Understanding how sea ice motion is going to change is clearly of interest, and yet we didn’t really know if what the models were projecting was reasonable,” says Tandon, who is also with the Centre for Research in Earth and Space Science (CRESS) at York University. “It seems that we can expect sea ice to continue to speed up for some time, but there will be a point in the coming decades when the dynamics will shift.”

Floating sea ice presents a particular hazard for marine transportation, says Tandon, pointing to a dramatic example from 2017 when sea ice trapped and sunk two fishing boats around Newfoundland. And the faster the ice, the more hazardous the conditions.

To understand why sea ice has been speeding up, Tandon says a spring can be a useful analogy. As temperatures warm and the ice thins, it can expand and contract more readily, just as a spring made of thinner metal can expand and contract more easily compared to a spring made of thicker metal.

“As the thinner sea ice expands and contracts more, it generates more momentum for the sea ice, just like one of those spring-loaded toy cars goes faster the farther back you pull it,” explains Tandon.

However, this is not the only force acting on the ice, and when the ice gets thin enough, the internal stresses that produced “springiness” start to fade and other forces start to dominate.

“As ice enters what they call a free drift state, the internal stress becomes negligible, and the external forces of wind and the ocean surface tilt start to dominate. The models suggest that changes in the wind and ocean surface tilt will drive a slowdown of the sea ice during the summer season.”

Tandon says that while the models generally agree that this summertime slowdown will occur, they do not agree on when this slowdown will start. Some models suggest that the slowdown will start within the next decade while others suggest it will start toward the end of this century.

Faster ice drifts can create hazardous conditions for marine transport, so in that sense an ice slowdown could be seen as a positive, but Tandon says there are bigger considerations.

“It doesn't change the fact that sea ice cover is steadily declining, right? This is a concern because of the impact on ecosystems, the Indigenous populations that rely on being able to hunt certain animals, the animals’ ability to survive the changing habitat, and the overall effect on the global climate,” says Tandon. “But, I would say it's marginally good news in that the models are suggesting that some of the worst aspects we were expecting about ice cover decline are not being projected.”

About Lassonde School of Engineering

Located in the heart of the multicultural Greater Toronto Area, Lassonde School of Engineering at York University is home to engineers, scientists and entrepreneurs, representing a diverse community of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners. With 11 undergraduate programs, seven graduate programs and a host of certificates and accessible study options, Lassonde is shaping the next generation of creators who will tackle the world’s biggest challenges and devise creative solutions through interdisciplinary learning opportunities. Lassonde’s creators think in big systems rather than small silos, design with people in mind and embrace ambiguity.

About York University

York University is a modern, multi-campus, urban university located in Toronto, Ontario. Backed by a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners, we bring a uniquely global perspective to help solve societal challenges, drive positive change, and prepare our students for success. York's fully bilingual Glendon Campus is home to Southern Ontario's Centre of Excellence for French Language and Bilingual Postsecondary Education. York’s campuses in Costa Rica and India offer students exceptional transnational learning opportunities and innovative programs. Together, we can make things right for our communities, our planet, and our future.

Media Contact: Emina Gamulin, York University Media Relations, 437-217-6362, egamulin@yorku.ca

END

The Lundbeck Foundation has announced the recipients of The Brain Prize 2024, the world’s largest award for outstanding contributions to neuroscience. This year’s award recognizes the pioneering work of three leading neuroscientists – Professor Larry Abbott at Columbia University (USA), Professor Terrence Sejnowski at the Salk Institute (USA), and Professor Haim Sompolinsky at Harvard University (USA) and the Hebrew University (Israel).

Theoretical and computational neuroscience permeates neuroscience today ...

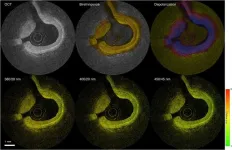

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a new catheter-based device that combines two powerful optical techniques to image the dangerous plaques that can build up inside the arteries that supply blood to the heart. By providing new details about plaque, the device could help clinicians and researchers improve treatments for preventing heart attacks and strokes.

Atherosclerosis occurs when fats, cholesterol and other substances accumulate on the artery walls, which can cause these vessels to become thick ...

(Boston)—Each year, approximately 2,000 people die annually of gallbladder cancer (GBC) in the U.S., with only one in five cases diagnosed at an early stage. With GBC rated as the first biliary tract cancer and the 17th most deadly cancer worldwide, pressing attention for proper management of disease must be addressed. For patients diagnosed, surgery is the most promising curative treatment. While there has been increasing adoption of minimally invasive surgical techniques in gastrointestinal malignancies, including utilization of laparoscopic ...

AMHERT, Mass.– Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently combined satellite data, field observations and sophisticated numerical modeling to paint a picture of how 22.45 million square kilometers of the Arctic will change over the next 80 years. As expected, the overall region will be warmer and wetter, but the details—up to 25% more runoff, 30% more subsurface runoff and a progressively drier southern Arctic, provides one of the clearest views yet of how the landscape will respond to climate change. The results were published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The Arctic is defined ...

(Boston)—Nearly all cervical cancers are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). New evidence has led to dramatic changes in cervical cancer screening recommendations over the past 20 years. In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) released updated guidelines for cervical cancer screening. The main changes to current practices were to initiate screening at age 25 instead of age 21 and to screen using primary HPV testing rather than cytology (PAP test) alone or in combination with HPV testing. Since adoption of guidelines often occurs slowly, understanding clinician attitudes is important ...

The Arctic could see summer days with practically no sea ice as early as the next couple of years, according to a new study out of the University of Colorado Boulder.

The findings, published March 5 in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, suggest that the first ice-free day in the Arctic could occur over 10 years earlier than previous projections, which focused on when the region would be ice-free for a month or more. The trend remains consistent under all future emission scenarios.

By ...

About The Study: In this study involving 247,000 UK residents, habitual short sleep duration was associated with increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This association persisted even among participants who maintained a healthy diet. To validate these findings, further longitudinal studies are needed, incorporating repeated measures of sleep (including objective assessments) and dietary habits.

Authors: Christian Benedict, Ph.D., of Uppsala University in Uppsala, Sweden, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi: ...

About The Study: In this multiyear cross-sectional study of a representative sample of young children in the U.S., the increased prevalence of high screen time in 2020 returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2021; however, it remained elevated in children living in poverty. Two hours or more of daily screen time was associated with lower psychological well-being among preschool-aged children.

Authors: Soyang Kwon, Ph.D., of Northwestern University in Chicago, is the corresponding author.

To access the ...

Adults who sleep only three to five hours a day are at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This is demonstrated in a new study from Uppsala University, published in JAMA Network Open. It also shows that chronic sleep deprivation cannot be compensated by healthy eating alone.

“I generally recommend prioritising sleep, although I understand it’s not always possible, especially as a parent of four teenagers,” says Christian Benedict, Associate Professor and sleep researcher at the Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences at Uppsala University and leading researcher behind the study.

He and a team of researchers have examined the link between type 2 ...

A novel screening system developed at Kyoto University enables researchers to investigate sperm cell development and health at the molecular level. The new approach, published in Cell Genomics, promises breakthroughs in male contraception and infertility treatments.

The study, led by Professor Jun Suzuki of the Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS), addresses a critical gap by directly targeting genes within testicular cells inside living organisms. Utilizing a genetic tool called CRISPR, which can ...