(Press-News.org) “Random DNA” is naturally active in the one-celled fungi yeast, while such DNA is turned off as its natural state in mammalian cells, despite their having a common ancestor a billion years ago and the same basic molecular machinery, a new study finds.

The new finding revolves around the process by which DNA genetic instructions are converted first into a related material called RNA and then into proteins that make up the body’s structures and signals. In yeast, mice, and humans, the first step in a gene’s expression, transcription, proceeds as DNA molecular “letters” (nucleobases) are read in one direction. While 80% of the human genome – the complete set of DNA in our cells – is actively decoded into RNA, less than 2% actually codes for genes that direct the building of proteins.

A longstanding mystery in genomics then is what is all this non-gene-related transcription accomplishing. Is it just noise, a side effect of evolution, or does it have functions?

A research team at NYU Langone Health sought to answer the question by creating a large, synthetic gene, with its DNA code in reverse order from its natural parent. Then they put synthetic gene into yeast and mouse stem cells and watched transcription levels in each. Published online March 6 in the journal Nature, the new study reveals that in yeast the genetic system is set so that nearly all genes are continually transcribed, while the same “default state” in the mammalian cells is that transcription is turned off.

Interestingly, say the study authors, the reverse order of the code meant that all of the mechanisms that evolved in yeast and mammalian cells to turn transcription on or off were absent because the reversed code was nonsense. Like a mirror image, however, the reversed code reflected some basic patterns seen in the natural code in terms of how often DNA letters were present, what they fell near, and how often they were repeated. With the reversed code being 100,000 molecular letters long, the team found that it randomly included many small stretches of previously unknown code that likely started transcription much more often yeast, and stopped it in mammalian cells.

“Understanding default transcription differences across species will help us to better understand what parts of the genetic code have functions, and which are accidents of evolution,” said corresponding author Jef Boeke, PhD, the Sol and Judith Bergstein Director of the Institute for Systems Genetics at NYU Langone Health. “This in turn promises to guide the engineering of yeast to make new medicines, or create new gene therapies, or even to help us find new genes buried in the vast code.”

The work lends weight to the theory that yeast’s very active transcriptional state is set so that foreign DNA, rarely injected into yeast for instance by a virus as it copies itself, is likely to get transcribed into RNA. If that RNA builds a protein with a helpful function, the code will be preserved by evolution as a new gene. Unlike a single-celled organism in yeast, which can afford risky new genes that drive faster evolution, mammalian cells, as part of bodies with millions of cooperating cells, are less free to incorporate new DNA every time a cell encounters a virus. Many regulatory mechanisms protect the delicately balanced code as it is.

Big DNA

The new study had to account for the size of DNA chains, with 3 billion “letters” included in the human genome, and some genes being 2 million letters long. While famous techniques enable changes to be made letter by letter, some engineering tasks are more efficient if researchers build DNA from scratch, with far-flung changes made in large swaths of pre-assembled code swapped into a cell in place of its natural counterpart. Because human genes are so complex, Boeke’s lab first developed its “genome writing” approach in yeast, but then recently adapted it to the mammalian genetic code. The study authors use yeast cells to assemble long DNA sequences in a single step, and then deliver the them into mouse embryonic stem cells.

For the current study, the research team addressed the question on how pervasive transcription is across evolution by introducing a synthetic 101 kilobase stretch of engineered DNA – the human gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1) in reverse coding order. They observed widespread activity of the gene in yeast despite the lack in the nonsense code of promoters, DNA snippets that evolved to signal for the start of transcription.

Further, the team identified small sequences in the reversed code, repeated stretches of adenosine and thymine building blocks, known to be recognized by transcription factors, proteins that bind to DNA to initiate transcription. Just 5 to 15 letters long, such sequences could easily occur randomly and may partly explain the very active yeast default state, the authors said.

To the contrary, the same reversed code, inserted into the genome of a mouse embryonic stem cells, did not cause widespread transcription. In this scenario, transcription was repressed even though evolved CpG dinucleotides, known to actively shut down (silence) genes, were not functional in the reversed code. The team surmises that other basic elements in the mammalian genome may restrict transcription much more so than in yeast, and perhaps by directly recruiting a protein group (the polycomb complex) known to silence genes.

“The closer we get to introducing a ‘genome’s worth’ of nonsense DNA into living cells, the better they can compare it to the actual, evolved genome,” said first author Brendan Camellato, a graduate student in Boeke’s lab. “This could lead us to a new frontier of engineered cell therapies, as the capacity to put in ever longer synthetic DNAs enables better understanding of what insertions genomes will tolerate, and perhaps the inclusion of one or more larger, complete, engineered genes.”

Along with Boeke and Camellato, NYU Langone study authors were Ran Brosh, Hannah Ashe, and Matthew Maurano. The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant 1RM1HG009491.

END

Synthetic DNA sheds light on mysterious difference between living cells at different points in evolution

2024-03-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AI can speed design of health software

2024-03-06

Artificial intelligence helped clinicians to accelerate the design of diabetes prevention software, a new study finds.

Publishing online March 6 in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, the study examined the capabilities of a form of artificial intelligence (AI) called generative AI or GenAI, which predicts likely options for the next word in any sentence based on how billions of people used words in context on the internet. A side effect of this next-word prediction is that the generative AI “chatbots” like chatGPT can generate replies to questions in realistic language, and produce clear summaries of complex texts.

Led ...

Shrinking technology, expanding horizons

2024-03-06

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and its collaborators have delivered a small but mighty advancement in timing technology: compact chips that seamlessly convert light into microwaves. This chip could improve GPS, the quality of phone and internet connections, the accuracy of radar and sensing systems, and other technologies that rely on high-precision timing and communication.

This technology reduces something known as timing jitter, which is small, random changes in the timing of microwave signals. Similar to when a musician is trying to keep a steady beat in music, the timing of these signals can sometimes waver a bit. The researchers ...

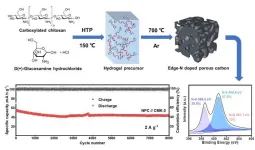

Edge-nitrogen doped porous carbon for energy-storage potassium-ion hybrid capacitors

2024-03-06

They published their work on March. 4th in Energy Material Advances, a Science Partner Journal (https://spj.science.org/journal/energymatadv).

"The development of cost-effective and high-performance electrochemical energy storage devices is imperative," said paper's corresponding author Wei Chen, a professor in the School of Chemistry and Materials Science, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). "Currently, lithium-ion batteries still dominate the market, but they are limited in both lithium as a resource and in their power densities."

Chen ...

Revolutionary elephant iPSC milestone reached in Colossal’s Woolly Mammoth Project

2024-03-06

Dallas, TX – March 06, 2024 - Colossal Biosciences (“Colossal”), the world’s first de-extinction company, announces today that their Woolly Mammoth team has achieved a global-first iPSC (induced pluripotent stem cells) breakthrough. This milestone advancement was one of the primary early goals of the mammoth project, and supports the feasibility of future multiplex ex utero mammoth gestation.

iPSC cells represent a single cell source that can propagate indefinitely and give rise to every other type of cell in a body. As such, the progress with elephant iPSCs extends far beyond ...

JAMA study finds facilities treating poor patients penalized by CMS payment model

2024-03-06

INDIANAPOLIS – A new study of more than 2,000 dialysis facilities randomized to a new Medicare payment model aimed to improve outcomes for patients with end-stage kidney disease has found that facilities that disproportionately serve populations with high social risk have lower use of home dialysis and transplant waitlisting and fewer kidney transplants. These facilities thus received reduced performance scores and reimbursement from Medicare.

A high proportion of non-Hispanic Blacks and of those initiating dialysis while uninsured or Medicaid-covered also was found to be an indicator of lower use of home dialysis and transplant waitlisting and fewer kidney ...

For Boston College professor, research into "high latitude" reaches of the seas led to improving accurate access to real-time ocean data

2024-03-06

Chestnut Hill, Mass (03/06/2024) – Boston College Assistant Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Hilary Palevsky has been awarded a nearly $1-million National Science Foundation CAREER Award for her work to make remote ocean monitoring data accessible and accurate in real time and produce a series of educational videos to guide students using the data.

Palevsky, whose research focuses on marine biogeochemistry and the mechanisms that enable the ocean to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, said the funding will allow her to build upon the work she has done to help scientists use the ...

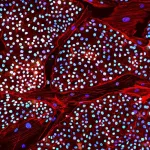

Microbes impact coral bleaching susceptibility, new study shows

2024-03-06

Washington, D.C. – March 6, 2024 – A new study provides insights into the role of microbes and their interaction as drivers of interspecific differences in coral thermal bleaching. The study was published this week in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

“The diversity, community dynamic and interaction of coral associated microorganisms play important roles in the health state and climate change response pattern of coral reefs,” said lead study author Biao ...

Study: Black boys are less likely to be identified for special education when matched with Black teachers

2024-03-06

WASHINGTON, March 6, 2024—Black male elementary school students matched to Black teachers are less likely to be identified for special education services, according to new research published today. The relationship is strongest for economically disadvantaged students. The study, by Cassandra Hart at the University of California, Davis, and Constance Lindsay at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill appeared in the American Educational Research Journal, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association.

The researchers also found that the connection is ...

A new genus of fungi on grasses

2024-03-06

While ecologically important, small mushrooms on monocots (grasses and sedges) are rarely studied and a lack of information about their habitat and DNA sequences creates difficulties in determining their presence or absence in ecological studies and their genetic relationships to other mushroom taxa.

This study led by Drs. Karen W. Hughes and Ronald H. Petersen (University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA) examined a mushroom species, Campanella subdendrophora, (also known as Tetrapyrgos subdendrophora), which fruits on grasses in the US Pacific Northwest.

The researchers evaluated its phylogenetic position concerning both Campanella and Tetrapyrgos ...

Allen Institute joins the Weill Neurohub

2024-03-06

SEATTLE, WASH.—March 6, 2024—The Allen Institute has officially become the newest member of the Weill Neurohub, a collaborative research network advancing treatments for neurological diseases.

Founded in 2003 by philanthropist Paul G. Allen, the Allen Institute focuses on big questions in biology through a team-based, open science approach, and currently has moonshot projects in neuroscience, cell biology, and immunology institutes.

The new partnership will integrate the Allen Institute’s expertise ...