(Press-News.org) Images

When climate scientists look to the future to determine what the effects of climate change may be, they use computer models to simulate potential outcomes such as how precipitation will change in a warming world.

But University of Michigan scientists are looking at something a little more tangible: coral.

Examining samples from corals in the Great Barrier Reef, the researchers discovered between 1750 and present day, as the global climate warmed, wet-season rainfall in that part of the world increased by about 10%, and the rate of extreme rain events more than doubled. Their results are published in Nature, Communications Earth and Environment.

"Climate scientists often find themselves saying, 'I knew it was going to get bad, but I didn't think it was going to get this bad this fast.' But we're actually seeing it in this coral record," said principal investigator Julia Cole, chair of the U-M Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

"Studies of the future tend to use climate models and those models can give different results. Some may say more rainfall, some they say less rainfall. We're showing that, at least in northeastern Queensland, there is definitely more rainfall, it's definitely more variable and it's definitely already happening."

The study, led by U-M researcher Kelsey Dyez, analyzed core samples drilled from a coral colony situated at the mouth of a river in northern Queensland, Australia. During the summer rainy seasons, rainfall filtering into the river picks up nutrients, organic material and sediments, which are then carried to the river mouth and discharged into the ocean, washing over the coral colony.

As the corals are bathed in this freshwater outflow, they pick up geochemical signals from the river and record them into their carbonate skeletons. The core samples of the corals display faint bands of lighter and darker material. These bands reflect each rainy and dry season the coral lived through. The bands also hold information about the climate in each season, just as trees' rings record climate patterns during the years it grows.

"We want to know, as we warm the earth, are we going to have more rainfall? Less rainfall? Maybe different parts of the Earth will respond differently?" Dyez said. "This project is especially important because we're able to put that warming and changes into context. We are able to record rainfall from the period before we have instrumental records for this part of the world."

To accurately determine how much rain fell each rainy season, and how many extreme rain events occurred during each season, the researchers compared instrumental rainfall records that began in the 1950s to the corresponding years in the coral. This gave the researchers a calibration period that they could use to determine the relationship between the coral characteristics and the amount of rainfall that fell each rainy season as long as the corals were alive, all the way back to 1750.

The coral core was taken from a remote region off northeastern Queensland by the Australian Institute of Marine Science. The land surrounding the river watershed is also in a protected area, meaning that nutrients and sediment flushed into the river by rains are unlikely to be generated by human activity.

"This is a region that has experienced pretty big swings in recent years between floods that have been devastating to communities, and then drier periods," Cole said. "Because northeastern Australia is an agricultural region, how rainfall changes in a warmer world is of real tangible importance. People might not sense a few degrees Celsius of warming, but they really suffer if there's a drought or a flood."

To reconstruct rainfall, the researchers used four different measures. First, the researchers looked at the luminescence of the bands in the coral. When they shine a black light on the coral, organic compounds in the coral cause it to fluoresce. The brighter the band fluoresces, the more organic compounds came down the river and were deposited onto the coral, reflecting a season of heavy rainfall.

The researchers also measured how much of the element barium is contained in each of the bands. The coral skeleton is composed of calcium, but when barium is deposited onto the skeleton, it can replace calcium. The more barium detected in the band, the more river discharge was flowing over the coral.

The researchers then looked at stable carbon isotopes (carbon-12 and carbon-13) within the coral. The more the ratio of these two isotopes favors carbon-12, the more water must have been coming down the river from greater rainfall.

Finally, the researchers examined stable oxygen isotopes (oxygen-16 and oxygen-18). When the ratio of these two isotopes favors oxygen-16, it is a signature of additional precipitation and freshwater coming down the river.

Because the coral record is located off northeastern Australia, the researchers wanted to understand if the whole of Australia experienced similar rainfall. Looking at instrumental rainfall records across Australia, the researchers found that the increased rainfall patterns did not occur evenly across Australia.

"It's not actually that well correlated to western Australia. That's too far away. But for most of eastern Australia, there is a significant correlation. And that's where many people live," Dyez said. "It's especially strong across Queensland, which is where a lot of these rainfall extremes are happening right now."

Study: Rainfall variability increased with warming in northern Queensland, Australia over the past 280 years (DOI: 10.1038/s43247-024-01262-5) (available when embargo lifts)

END

A wetter world recorded in Australian coral colony

2024-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Weight loss caused by common diabetes drug tied to “anti-hunger” molecule in study

2024-03-18

An “anti-hunger” molecule produced after vigorous exercise is responsible for the moderate weight loss caused by the diabetes medication metformin, according to a new study in mice and humans. The molecule, lac-phe, was discovered by Stanford Medicine researchers in 2022.

The finding, made jointly by researchers at Stanford Medicine and at Harvard Medical School, further cements the critical role the molecule, called lac-phe, plays in metabolism, exercise and appetite. It may pave the way to a new class of weight loss drugs.

“Until now, the way metformin, which is prescribed to control blood sugar ...

Intermittent food intake activates a 'GPS gene' in liver cells, thus completing the development of the liver after birth

2024-03-18

After birth, liver cells acquire different functions depending on their location. CNIO researchers have discovered that this specialization occurs with the onset of oral food intake, which is intermittent.

The alternation of periods with and without nutrients activates the mTOR gene and causes liver cells to specialize, which completes liver maturation.

The finding is the result of an investigation into the consequences of sedentary lifestyles and overeating in today’s society, where the body ...

Scientists reveal chemical structural analysis in a whiff of smell

2024-03-18

Scents, such as coffee, flowers, or freshly-baked pumpkin pie, are created by odor molecules released by various substances and detected by our noses. In essence, we are smelling molecules, the basic unit of a substance that retains its physical and chemical properties.

A research team led by Dr. ZHOU Wen from the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has discovered that this process of "smelling" involves an analysis of submolecular structural features.

The study was published online in Nature Human Behaviour on March 18.

In this study, the ...

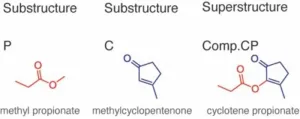

Using light to produce medication and plastics more efficiently

2024-03-18

Anyone who wants to produce medication, plastics or fertilizer using conventional methods needs heat for chemical reactions – but not so with photochemistry, where light provides the energy. The process to achieve the desired product also often takes fewer intermediate steps. Researchers from the University of Basel are now going one step further and are demonstrating how the energy efficiency of photochemical reactions can be increased tenfold. More sustainable and cost-effective applications are now tantalizingly close.

Industrial chemical reactions ...

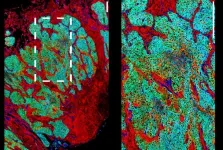

Mapping the evolution of urinary tract cancer cells

2024-03-18

Researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine have performed the most comprehensive analysis to date of cancer of the ureters or the urine-collection cavities in the kidney, known as upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). The study, which compared the characteristics of primary and metastatic tumors, provides new insights into the biology of these aggressive cancers and potential ways to treat them.

In the study, which appeared March 18 in Nature Communications, the researchers examined tissue samples from 44 primary and metastatic UTUC tumors. They compared gene mutations ...

Implantable sensor could lead to timelier Crohn’s treatment

2024-03-18

· Temperature sensor warns of disease flareups, tracks disease progression in real time

· Currently no way to quickly detect inflammation, leading to invasive surgeries

· Strategy could be useful in ulcerative colitis, another inflammatory bowel disease

CHICAGO --- A team of Northwestern University scientists has developed the first wireless, implantable temperature sensor to detect inflammatory flareups in patients with Crohn’s disease. The approach offers long-term, real-time monitoring and ...

Glucose levels affect cognitive performance in people with type 1 diabetes differently

2024-03-18

A new study led by researchers at McLean Hospital (a member of Mass General Brigham) and Washington State University used advances in digital testing to demonstrate that naturally occurring glucose fluctuations impact cognitive function in people with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). Results showed that cognition was slower in moments when glucose was atypical – that is, considerably higher or lower than someone’s usual glucose level. However, some people were more susceptible to the cognitive effects of large glucose fluctuations than others.

“In trying to understand how diabetes impacts the brain, our research shows that it is important to consider not only how people ...

Mimicking exercise with a pill

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 — Doctors have long prescribed exercise to improve and protect health. In the future, a pill may offer some of the same benefits as exercise. Now, researchers report on new compounds that appear capable of mimicking the physical boost of working out — at least within rodent cells. This discovery could lead to a new way to treat muscle atrophy and other medical conditions in people, including heart failure and neurodegenerative disease.

The researchers will present their ...

New composite decking could reduce global warming effects of building materials

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 — Buildings and production of the materials used in their construction emit a lot of carbon dioxide (CO2), a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming and climate change. But storing CO2 in building materials could help make them more environmentally friendly. Scientists report that they have designed a composite decking material that stores more CO2 than is required to manufacture it, providing a “carbon-negative” option that meets building codes and is less expensive than standard composite decking.

The researchers will present their results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society ...

Artificial mucus identifies link to tumor formation

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 – During cold and flu season, excess mucus is a common, unpleasant symptom of illness, but the slippery substance is essential to human health. To better understand its many roles, researchers synthesized the major component of mucus, the sugar-coated proteins called mucins, and discovered that changing the mucins of healthy cells to resemble those of cancer cells made healthy cells act more cancer-like.

The researcher will present her results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2024 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in person March 17-21; it features nearly 12,000 ...